Your friend contests whomever you contest | صديقك من يعادي من تعادي

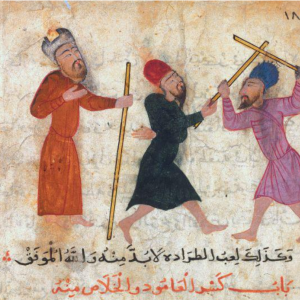

Page from a manuscript on horsemanship, Hegira 9th century / AD 15th century, Paper with watercolour painting and writing in black and red ink. Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo [Image in Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

“Your friend contests whomever you contest” comes from the collected works ascribed to Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī, better known as al-Imām al-Shāfiʿī (767-820). The great belletrist ʿAbd al-Mālik al-Thaʿālibī (d.1038) marshals these verses in blame of friendship in his famous anthology, Yāwāqīt al-Mawāqīt fī Madḥ Kull Shayʾ wa-Dhammihi wa-Tazyīnihi wa-Tahjīnihi [Rubies of the Ages in Praise, Blame, Adornment, and Debasement of Everything], alternatively titled al-Laṭāʾif wa-al-Ẓarāʾif [The Subtle and Eloquent (Expressions)]. The anthology bespeaks an age’s incessant knack for wit. With the right evidence, eloquence, and sense of humor, authors absurdly uglified the beautiful and beautified the ugly.

We have no extant manuscripts from his period that include al-Shāfiʿī’s poetic works, which appeared in various anthologies since the Middle Ages. Only relatively recently, at the turn of the twentieth century, was the poetry ascribed to him published in a single dīwān, or poetry collection. These poems were penned by different hands at different points in history. In the preface to his second edition of the dīwān, Dr. Mujāhid Bahjat notes that the majority of poems ascribed to al-Shāfiʿī may be ascribed to other poets or are otherwise unconfirmed as his own; he traces only twelve directly to him, whereas a given edition may include over 160 poems and poetic fragments [Bahjat, 3-4, 19-20].

Although primarily recognized as the namesake to one of the four main jurisprudential schools (or madhāhib, sg. madh’hab) in Sunni Islam, al-Imām al-Shāfiʿī equally distinguished himself as a master of language and adab (belles-lettres). Growing up, this descendant of the prophetic line of the Banū Hāshim tribe lived among the Hudhayl—a clan known for the purity of their Arabic—in order to immerse himself in the study of the language. This training made his reputation as a poet and poetic critic. Years later, in Baghdad, the famed philologist and grammarian al-Aṣmaʿī (d.828) would visit al-Shāfiʿī to take Hudhalī poetry from him. As did all eminent scholars who sought him out (there were many), he marveled at his double command of language and poetry.

al-Imām al-Shāfiʿī was born in Gaza in 767. With the death of his father, he and his mother moved to Mecca two years later. His pursuit of ṭalab al-ʿilm (knowledge) brought him at a young age to Medina, where he studied ḥadīth (prophetic narrations) and fiqh (Islamic law) under al-Imām Mālik ibn Anas until the latter’s death in 795. He then accepted a post in Yemen as governor of Najran, although a revolt in 803 prematurely ended his political career when it led to his arrest and summoning to the court of the Abbasid caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd (d.809) in al-Raqqah, a city in Syria. There, he would meet the jurist Muḥammad al-Shay-bānī (d.805), who helped secure his acquittal. Under al-Imām al-Shaybānī’s tutelage, al-Shāfiʿī relocated to Baghdad. Among al-Shāfiʿī’s most important students there was al-Imām Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal (d.855). al-Shāfiʿī would make one more major move in 814 for Egypt, where he continued to study and teach a variety of subjects, primarily jurisprudence, until his death in 820 at the age of 54.

The verses ascribed to al-Shāfiʿī probably reflect a lifetime’s worth of occasional compositions and pronouncements, and cer-tainly reflect their author’s erudition, fine manners, and familiarity with classical meters. Precise and brief, the poetry employs a range of sophisticated rhetorical strategies nevertheless, from ṭibāq (contrariety) to bayān (eloquence), to jinās (paronomasia), to additional instances of badīʿ (ingenuity)—stylistically unique tropes and schemes [Bahjat, pp. 29-37, 42-43]. Thematically, the poems touch on the matters of wisdom literature, including personal comportment, friendship, the pursuit of knowledge, and the cultivation of virtues.

Further Reading

Bahjat, Mujāhid Muṣṭafā, editor. “Muqaddimat al-Ṭabʿah al-Thāniyah” [“Preface to the Second Edition”]. In Dīwān al-Shāfiʿī: al-Imām al-Faqīh Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī, Dimashq: Dār al-Qalam, 1999.

Chaumont, E. “al-Shāfiʿī”, In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., edited by P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, and E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs, 2012. Consulted online on 25 August 2020 .

Farrin, R. Abundance from the Desert: Classical Arabic Poetry. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2017.

van Gelder, G., editor. Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology. New York: New York University Press, 2012.

van Gelder, G. “Beautifying the Ugly and Uglifying the Beautiful: The Paradox in Classical Arabic Literature.” Journal of Semitic Studies, Volume 48, Issue 2, Autumn 2003: 321–351.

“Your friend contests whomever you contest” | “يداعت نم يداعي نم كقيدص”

مُامحلا عجس ام رهدَّلا لوطب مُاود اًدبَأ هب ننُمي الو

5 مُاهسِّلا كقُشُرت نيح حرفيو مارح هتبحصُف هبنَّجت

:مُاظنِّلا هنُيز ردُّلا هيبش

10

مُالكلا لصَفَناو ،كاداع دقف”

يداعت نم يداعي نم كقيدص لٍطْمَ ريغب كنع نَيدَّلا يفويُو يداعت نمَ كقيدص ىفاص نإف كٍّش ريغب وُّدعلا وه كاذف

رٍعش تيب انعمس دق انَّإف

“يداعتُ نمَ كقيدص ىفاو اذإ

Your friend contests whomever you contest

So long as pigeons coo;

Pays without delay your debt,

Never guilting you.

Should your friend your foe underwrite,

Enjoying arrows’ flight,

Then surely he’s the foe, no doubt.

Quit him. His friendship’s out.

We heard a verse,

Pearly in its framework:

“Once your friend upholds your foe, he

Crosses, end of story.”