Song IV "Go quickly, little letter" | Carmen IV "Cartula, perge cito"

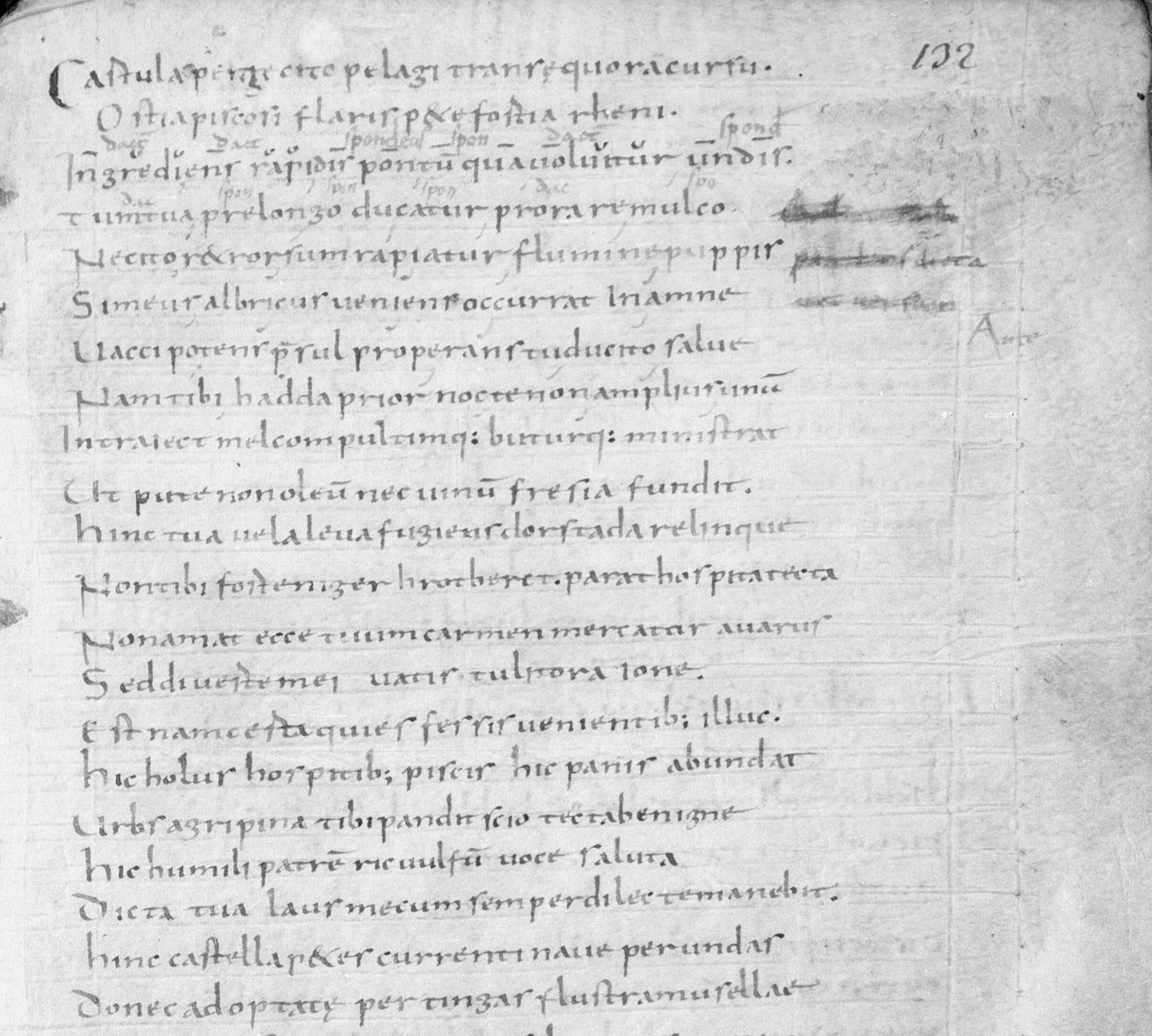

Paris BNF MS Latin 528 f.140v [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

Alcuin (c.735–804 AD) was one of the leading figures in the so-called “Carolingian Renaissance”—the renewal or reinvigoration of education and literary/artistic production during the reign of Charlemagne (r.768–814) over the Frankish kingdom in Western Europe (encompassing much of modern France, Germany, the Low Countries and northern Italy). Alcuin was originally from York in Northumbria (what is now the North of England). He was educated at the Cathedral school in York, where he became known as a master of the liberal arts.

In c.780, he traveled to Rome to receive the pallium (a sign of papal authority) for Eanbald, Archbishop of York, meeting Charlemagne for the first time on his return journey (later in the decade, he would be invited to move permanently to Charlemagne’s court, where he began his task of educational and literal renewal). On his return to England, he is believed to have written this short Latin poem, “Cartula perge cito” (“Go quickly, little letter”). It was likely composed no later than 782, since it addresses Bassinus, who ceased to be bishop of Speyer in this year. In this poem, he sends a letter of greetings to the people he met on the way to and/or from Rome. The central conceit of the poem is that Alcuin addresses (or “apostrophizes”) the letter itself, telling it to make its way down the Rhine river from Utrecht, through Cologne, to Charlemagne’s court (which was itinerant at this point, with no fixed capital), and on to Mainz, Speyer and finally to Saint-Denis (in an odd departure from the route). Given the detail of the description of the places on the way, it seems probable that the letter is following Alcuin’s own journey—for a traveler coming from the North of England, the Rhine would have been a relatively quick and safe route for travel into Italy and onto Rome.

Travel literature per se is relatively rare in the early Middle Ages. As such, this poem offers remarkable insight into a major trading and pilgrimage route—the journey itself and the places and people encountered along the way. The letter’s (or Alcuin’s) arrival in Frisia is particularly striking for its treatment of the issue of lodging—the need for the traveler (in the days before travel agents and Airbnb!) to find accommodation and food on what would have been a long, uncertain journey. It is easy to imagine why Alcuin would warn travelers off the grim merchant Hrotberht in the bustling trading emporium of Dorestad—one imagines there were plenty of unwelcoming and unsavory inns and hostelries to contend with on such a journey. Elsewhere there are other charming details, like Alcuin’s fear that his gift of a grammatical manuscript might end up at the bottom of the sea.

The poem is written in dactylic hexameters, the same meter used by Virgil, and the most common form of Latin verse in the early Middle Ages; it had previously been used by Alcuin’s great English predecessors, Aldhelm and Bede. Other Latin poets had used the conceit of a letter—most notably Sidonius Apollinaris’s Carmen 24, in which he sends his liber on a journey from Clermont to Narbonne. Sidonius, like Alcuin, divided his poem into a series of “frames” which fragment the letter’s itinerarium (journey) into a series of vignettes. In terms of style, the poem is also reminiscent of Virgil’s Eclogues, a series of relatively short pastoral pieces on a variety of subjects. Although little in the poem is “pastoral” in the strictest sense (there is no shepherd to be found, although there is a “cow-lord bishop”), Alcuin nevertheless evokes a world of rich produce, of “flower-filled fields” and calm rivers, a world in which one does not merely introduce oneself, but “knocks on the doors with Castalian lyre.” Alcuin quotes from Eclogue 8 in the poem, perhaps as a signal to learned readers that he was operating in this mode. At the same time, there are also echoes of Roman satire (especially Horace) in Alcuin’s playful, prodding addresses to his friends.

Introduction to the Source

The poem is preserved in a single manuscript, Paris, BNF, lat. 528. The manuscript is a complex compendium of poetic, grammatical and rhetorical texts, most notably including numerous epistles and poems by Paul the Deacon (d. 799). It is believed to have been compiled in Saint-Denis (near Paris) during the abbacy of Fardulf (793–806). Fardulf’s predecessor, Fulerad, is the last person addressed in Alcuin’s poem, which suggests that the “little letter” did in fact make the journey on which Alcuin sent it. It can certainly be dated to the first half of the ninth century on palaeographical grounds. By the eleventh century it had moved to the Abbey of Saint Martial in Limoges (in west-central France); it was transferred to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France at Paris in 1730.

About this Edition

The standard edition of Alcuin’s poetry remains Ernst Duemmler’s edition from 1881 (Poetae Latini Aevi Carolini, Vol. 1, MGH). I have not attempted to translate into verse, but I have preserved the linebreaks of the original. I have added paragraph breaks corresponding to the poem’s “frames,” as described by Sinisi.

Further Reading

Bullough, Donald A. Alcuin: Achievement and Reputation. Brill, 2004.

- A useful (if slightly scattershot, having been edited posthumously from the author’s papers) introduction to Alcuin’s achievements.

Godman, Peter. Poetry of the Carolingian Renaissance. Duckworth, 1985.

- A wide range of Carolingian poems in English translation (with Latin facing).

Godman, Peter. Poets and Emperors: Frankish Politics and Carolingian Poetry. Clarendon Press, 1987.

- One of the only full-length studies of Carolingian Latin poetry in English.

Sinisi, Lucia. “From York to Paris: Reinterpreting Alcuin’s Virtual Tour of the Continent.” Anglo-Saxon England and the Continent, edited by Hans Sauer and Joanna Story with the assistance of Gaby Waxenberger, ACMRS, 2011, pp. 275–92.

- An excellent recent study of the poem.

Zironi, Alessandro. “An Educational Miscellany in the Carolingian Age: Paris, BNF, lat. 528.” Medieval Manuscript Miscellanies: Composition, Authorship, Use, edited by Lucie Dolez̆alová and Kimberley Rivers, Medium Aevum Quotidianum, 2013, pp. 168–81.

- A recent study of the manuscript in which the poem is found.

Song IV “Go quickly, little letter” | Carmen IV “Cartula, perge cito”

Cartula, perge cito pelagi trans aequora cursu,

Ostia piscosi flabris pete fortia Rheni,

Ingrediens rapidis pontum qua volvitur undis.

Tum tua prelongo ducatur prora remulco,

5 Ne cito retrorsum rapiatur flumine puppis.

Si meus Albricus veniens occurrat in amne

‘Vaccipotens praesul’, properans tu dicito, ‘salve’,

Nam tibi Hadda prior nocte non amplius una

In Traiect mel compultimque buturque ministrat:

10 Utpute non oleum nec vinum Fresia fundit.

Hinc tua vela leva, fugiens Dorstada relinque:

Non tibi forte niger Hrotberct parat hospita tecta,

Non amat ecce tuum carmen mercator avarus.

Sed diverte mei vatis tu litora Ione:

15 Est nam certa quies fessis venientibus illuc,

Hic holus hospitibus, piscis hic, panis abundat.

Urbis Agripina tibi pandit, scio, tecta benigne:

Hic humili patrem Ricvulfum voce saluta;

Dic: ‘Tua laus mecum semper, dilecte, manebit’.

20 Hinc castella petes currenti nave per undas,

Donec ad optatae pertingas flustra Musellae.

Remigio postquam spatium sulcaveris amnem,

Hic tum siste ratem, puppis potiatur harena,

Et pete Wilbrordi patris loca sancta pedester

25 Atque sacerdotis Samuhelis tecta require

Castalido portas plectro pulsare memento,

Constanter puero Pithea dic voce ministro:

‘Puplius Albinus me misit ab orbe Brittanno

Predulci dulcem patri perferre salutem’.

30 Si tibi praesentis fuerit data copia verbi,

Fusa solo supplex plantas tu lambe sacratas,

Dicque ‘Valeto, pater Samuhel’, dic ‘Vive sacerdos’.

Detege iam gremium, patres et profer honestos

Priscianum, Focam, tali quia munere gaudet,

35 Si non Neptunus pelago demerserit illos.

Se te forte velit regis deducere ad aulam,

Hic proceres patres fratres percurre, saluta.

Ante pedes regis totas expande camenas,

Dicito multoties: ‘Salve, rex optime, salve.

40 Tu mihi protector, tutor, defensor adesto,

Invida ne valeat me carpere lingua nocendo

Paulini, Petri, Albrici, Samuelis, Ione,

Vel quicumque velit mea rodere viscere mursu:

Te terrente procul fugiat, discedat inanis’.

45 Mormure dic tacito: ‘Cathegita Petre valeto!

Herculeo sevus clavo ferit ille, caveto’!

Paulini gaudens conplectere colla magistri,

Oscula melligeris decies da blanda labellis.

Ricvulfum, Raefgot, Radonem rite saluta,

50 Auriculas horum peditemtim tange canendo,

Dic: ‘Socii fratres laiti salvete valete’.

Egregiam forsan venies Maggensis ad urbem

Perpetuumque vale doctori dicito Lullo,

Ecclesiae specimen, sophiae qui splendor habetur,

55 Moribus et vita tanto condignus honore.

O Bassine bone, Spirensis gloria plebis,

Me, rogo, commenda Paulo, pater alme, patrono,

Cuius et alma domus fratres nos fecerat ambos.

Quis, Fulerade pius, lyrico te tangere plectro

60 Audebit? meritis Musarum carmina vincis.

Nunc tamen hanc ederam circum sine timpora sacra

Serpere, summe pater, tibimet bonitate sueta,

Vel demitte semel memet tibi dicere salve.

Heia age, carta, cito navem conscende paratam;

65 Oceanum Rhenum sub te natet unca carina.

Materies auri non te, rogo, fulva retardet,

Accula quem fessus profert de viscere terrae.

Non castella, domus, urbes, nec florida rura

Deteneant stupidam spatio nec unius horae,

70 Sed fuge, rumpe moras, propera, percurre volando:

Incolomes sanos gaudentes atque vigentes

Invenies utinam nostros gratanter amicos.

Det deus omnipotens illis per secla salutem,

Postea caelestem laetos deducat in aulam.

75 Omnibus his actis patriam tu certa reverte,

Et quod quisque tibi dicat narrare memento,

Ut cum vere novo rubrae de cortice gemmae

Erumpant, nostris videam te ludere tectis,

Atque novas iterum nobis adferre camenas.

80 Tum tibi serta novis de floribus aurea fingam

Et sociata mihi pratis pausabis amoenis.

Go quickly, little letter, across the even surface of the sea.

Seek out on the breeze the strong harbors of the fish-laden Rhine,

Which enters the sea where it is turned about with rushing waves.

Then your prow may be led by a very long tow-rope,

5 Lest the vessel be seized back by the river.

If my Albricus should come and meet you on the river,

Hastily say, “O Cow-Lord Bishop, greetings,”

Because Prior Hadda will serve you honey and porridge and butter

In Utrecht, no more than a night’s walk from where you landed

10 (Since Frisia pours out neither oil nor wine).

Raise your sails here; flee and leave Dorestad behind.

I suspect black Hrotberht will not prepare friendly lodging for you;

See, the greedy merchant does not love your song.

But pay a visit to the shores of my prophet Jonas.

15 For there is surely rest for weary travellers in that place;

Here vegetables, here fish and bread abound for guests.

I know the city of Cologne will kindly spread out lodgings for you:

Here greet father Ricwulf with humble voice;

Say, “Your praise will remain with me always, beloved.”

20 Here you will seek out the fortified towns with a ship running through the waves,

Until you reach the calm waters of the pleasant Moselle.

After you have plowed this wide river with your oar,

Make your raft to stand here – let your ship occupy the sand – And seek the holy places of father Willibrord on foot.

25 Find the dwellings of the priest Samuel.

Remember to knock on the doors with Castalian lyre,

Constantly saying with Pythean voice to the servant boy:

“Puplius Albinus sent me from the British world

To bring sweet greetings to a most kind father”.

30 If an abundance of words is granted to you in person,

Pour it out and go down on your knees to kiss his holy heels,

And say, “Farewell, father Samuel”, say, “Live well, priest!”

Unlock your bounty and bring forth the honorable fathers

Priscian and Foca, for he delights in such a gift –

35 If Neptune hasn’t plunged them into the sea!

If he wants to take you to the king’s court,

Quickly review the nobles, fathers, and brothers there, and greet them.

Spread out all your poetry at the feet of the king

And say again and again, “Greetings, best of kings, greetings!

40 Be to me a protector, guardian, and defender,

Lest jealous tongues seize me to do me harm –

Those of Paulinus, Peter, Albricus, Samuel and Jonah

Or of anyone who wishes to gnaw my flesh with biting.

Let him flee away from you in terror; let the fool depart.”

45 Say quietly in a murmur, “Farewell, Peter my maestro!

Beware! That savage strikes with a Herculean club.”

Rejoicing, throw your arms around the neck of master Paulinus;

Give him ten charming kisses on his honey-bearing lips.

Greet Ricwulf, Raefgot and Rado in the right way;

50 Touch their ears little-by-little with your singing.

Say, “My happy companions, brothers, hail and well-met!”

Perchance you will come to the excellent and unchanging city of Mainz;

Say hello to the doctor Lull,

A model for the church, who is considered the splendour of wisdom,

55 Worthy of such honour for his customs and life.

O good Bassinus, glory of the people of Speyer:

I ask you, nourishing father, to commend me to your patron Paul,

Whose nourishing house had made us both brothers.

Who will dare to touch you, pious Fulerad, with a plucked lyric?

60 You surpass the songs of the muses with your merits.

But now let this ivy creep around your holy temples,

High father, through your kind goodness,

Or let me just once say ‘greetings’ to you.

Right then, letter, get on board the ship – it’s ready to go:

65 The curved keel will sail the Rhenish seas beneath you.

I pray that no yellow matter of gold may slow you down,

Which the weary countryman brings up from the bowels of the earth.

Let not strongholds, houses, cities, or flower-filled fields

Hold you back, dumbstruck, for the space of even one hour,

70 But fly! Put an end to delay! Make haste and take flight!

I hope you joyfully find our friends

Unharmed, in good health, enjoying life and on good form.

May almighty God give them health in the present world

And afterwards lead them happy into his heavenly court.

75 After doing all these things, be sure you return to your homeland,

And do remember to tell me anything anyone said to you.

So that, when the red fruits are bursting forth from new bark

In the spring, I will see you playing under our roof,

And bringing us back new songs.

80 Then will I fashion a golden wreath of new flowers for you,

And, reunited with me, you will rest in pleasant meadows.

Critical Notes

Transcription

Line 46: Ms. claro, following emendation of Schaller (1970)

Translation

Line 6: Bishop of Utrecht (Traiectum), d.784.

Line 8: Alcuin uses a Germanicism butur (as opposed to butyrum).

Line 11: A trading emporium in Frisia, a few miles downstream from Utrecht, now known as Wijk bij Duurstede.

Line 14: Otherwise unknown, although he must have been a reasonably significant individual, given that he is mentioned again alongside several very notable figures in line 42.

Line 18: Bishop of Cologne, 772–794.

Line 24: Northumbrian missionary to the Frisians (c.658–739). Alcuin wrote a Life of Willibrord in both prose and verse.

Line 25: Beornrad, Abbot of Echternach (where Willibrord was buried) 776–798, from 785/6 also archbishop of Sens, at whose request Alcuin wrote the Life of Willibrord.

Line 28: In his later letters, Alcuin used the pseudonym Flaccus (“Flabby”) Albinus. “Puplius” here perhaps is meant to evoke Publius, the praenomen of the poets Virgil, Ovid and Statius. If the substitution of “pup” for “pub” is not due to scribal error, it is perhaps meant to suggest pupus/pupulus/pupillus – Alcuin is merely a “pupil” of the master poets.

Line 34: Two fifth-century Latin grammarians.

Line 42: Paulinus of Aquileia, Peter of Pisa, two leading figures in the Carolingian Renaissance.

Line 45: Cathegita, a rare word even in Greek (but cf. Matthew 23:10), occurs three times in Alcuin’s carmina.

Line 53: Lull or Lullus (d.786) was an English missionary and successor to St Boniface as Bishop of Mainz. Mainz was elevated to an Archbishopric in 781—it is not clear whether Alcuin was writing before or after this event.

Line 56: Bishop of Speyer until 782.

Line 57: Paul the Deacon, the highly influential Lombard scholar.

Line 59: Abbot of Saint-Denis, near Paris (d.784). This is an odd departure from the main route of the letter’s journey. Given that the poem survives in a Saint-Denis manuscript, I wonder if these lines represent an off-the-cuff addition to the poem, unless Alcuin expected Bassinus to pass the cartula on to Fulerad (perhaps making the poem a kind of Rhineland travelogue addressed to Fulerad).

Line 61: Cf. Virgil, Eclogues, 8.11-13.