First Decade of Asia, Chapter 1 | Primeira Década da Asia, Capitulo I

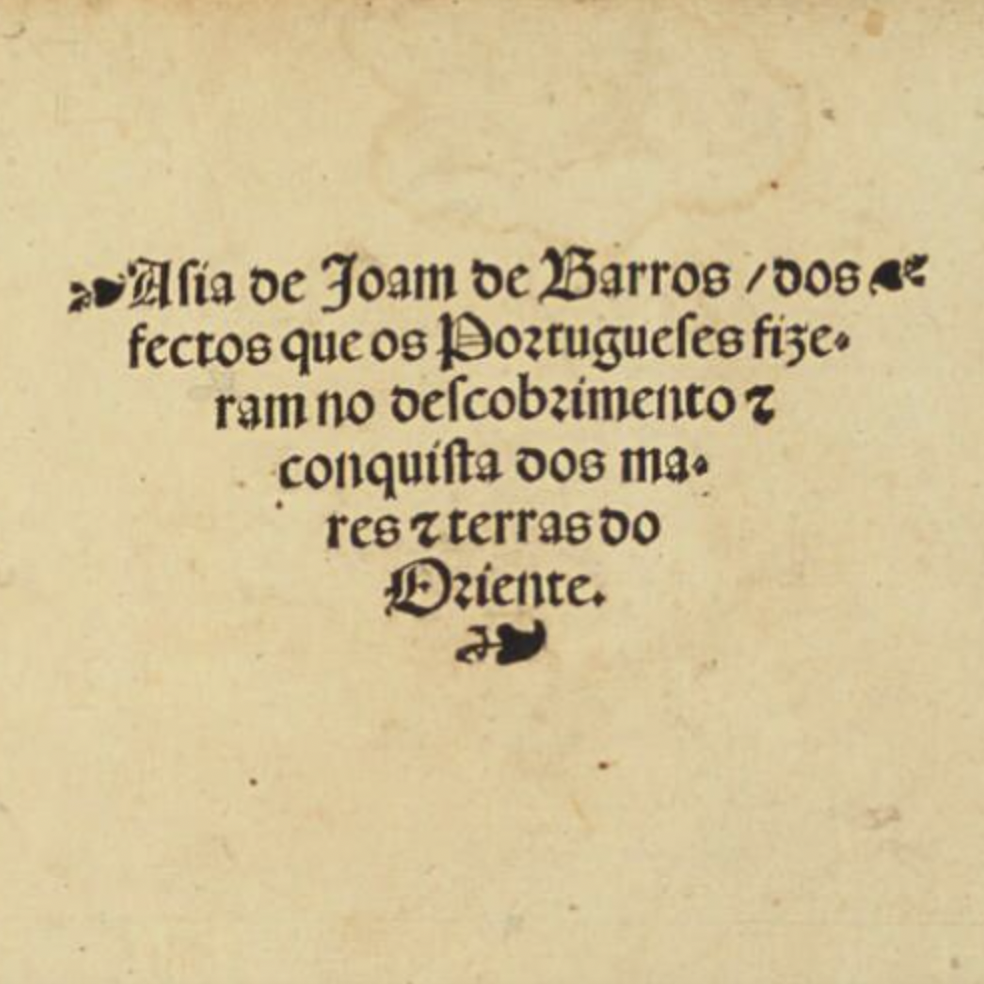

Detail from the title page of _Asia de Joam de Barros / dos fectos que os Portugueses fizeram no descobrimento e conquista dos mares e terras do Oriente_ (Lisbon: Germão Galharde, 1552).

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

Written by Portuguese historian and civil servant João de Barros (c. 1496-1570), the Decades of Asia (1552–1615) is a four-volume history, one of the earliest and most monumental accounts of Portuguese colonial endeavors. Barros wrote the Decades while he was serving as the factor (financial administrator) of the Casa da India e Mina (House of India and Mines) (1533–67), an appointment he obtained a few years after he returned from working in West Africa. The first three volumes cover the period until 1539, and were published in 1552, 1553, and 1563. Although Barros started working on the last volume, it was only published posthumously in 1615. The fourth volume was finished by Diogo do Couto, who was at the time the royal archivist of Portugal’s official archive in India and who continued Barros’s gargantuan project of writing a comprehensive history of Portuguese colonialism.

The excerpt translated here—Chapter 1 of the Decades, which works like an introduction—offers a glimpse of how Barros frames the history of Portuguese colonial efforts as part of a much longer struggle between Christians and Muslims, both in the Iberian Peninsula and elsewhere. In this regard, the Decades is similar to other Portuguese chronicles from the medieval and early modern periods: although it has a specific subject matter—in this case, Portugal’s colonial enterprise in Africa and Asia—the history spans a longer period, connecting the subject matter to other events which Barros thought were relevant for his audience to understand Portugal’s maritime expansion. In particular, his choice to begin his history of Portuguese colonialism with the emergence of Islam in the Arabian Peninsula has very important rhetorical consequences as it justifies Portugal’s colonial expansion as a response to what he saw as an invasion of the Iberian Peninsula by Muslim kingdoms.

By beginning his history with the emergence of Islam and with the events that led to a substantial Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula, Barros frames the Decades and the whole project of Portuguese colonialist expansion as a religious conflict between Christianity and Islam. As a Christian historian, Barros attempts to insert such events into a broader Christian framework, according to which the Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula (the area that is now Spain and Portugal) was God’s intended punishment for heresies adopted by the local peoples (when Barros refers to “Spain” during periods that precede the creation of Portugal, he most likely means Hispania, the Roman name given to the entire Iberian Peninsula).

It is noteworthy that most of Barros’s narrative of Muslim expansion focuses on the Middle East and North Africa, and not on the Iberian Peninsula. Particularly intriguing is how he omits any mention of Al-Andalus—the part of the Iberian Peninsula ruled by Muslims between 711 and 1492—and how he glosses over both the Caliphate of Cordoba, a successful Muslim state in the Iberian Peninsula, and the thriving Muslim states that formed after the Caliphate’s collapse. In sum, Barros’s selection of events in his inaugural chapter—from the very first sentence—offers an image of multiple Muslim-ruled regions in Asia and Africa that represented a historical and constant Muslim threat, all the way up to the closest point to the Iberian Peninsula, conquered by an expansionist leader and his descendants.

Although the first chapter of the Decades focuses on the religious conflict between Christianity and Islam by painting Muslims as conquerors—a kind of rival empire to the Christian Portuguese one—this framing of events actually transcends the specific conflict between Christians and Muslims. In other words, Barros sets the stage for a broader narrative of Christian expansion that he will expand on in later parts of the work, including the same theme of religious conflict but against other beliefs and customs, such as in India. He goes as far as to claim that the royal house of Portugal, which was created during the Reconquista (the name given to the many wars waged by Iberian Christian kingdoms against Muslim states in the Peninsula) was founded with the blood of martyrs and expanded by martyrs across all regions of the world. According to Barros’s frame, it is almost as if the events surrounding the founding of the Portuguese kingdom have endowed it with the moral duty to expanding Christianity throughout the universe.

After making such claims about Portugal’s higher purpose, he then considers a more pragmatic issue: Portugal was only a sliver of European territory and most of the Iberian Peninsula belonged to Castile, so Barros hints that Portuguese maritime expansion was the only option left for Portugal to grow as a kingdom. In fact, Portugal’s colonialist expansion, according to Barros, mirrors Rome’s expansion onto North Africa, implying that the legacy of the Roman empire rested with Portugal in the sixteenth century.

This introductory chapter to the Decades encapsulates a broader tendency of early modern European historians: the division of subject matter according to fields of knowledge. In early modernity, the division of knowledge between different domains was very different from that of the modern period. Early modern historians often combined what we would consider different domains of knowledge (resembling what we would now call ethnography, sociology, history, geography, and natural history) in their accounts of the world’s peoples and regions, and divided their content along different lines.

Here Barros divides the Portuguese colonial enterprise into three broad fields of inquiry and four geographic regions. According to him, these fields and subject matters are interrelated, but distinct: the first is conquest, which covers the military side of colonialism, i.e. the history of different battles; the second is navigation, which is concerned with what modern readers would call physical geography; and the third is commerce, which deals with the culture of all places that Portugal had conquered or sought to conquer. It is from this third field of enquiry that Barros draws general principles for understanding human cultures—with the implication that this understanding is only made possible by colonialist enterprise. Unfortunately, all the other parts of his project have since been lost: his universal Geography, his treatise on human culture called Commerce, and the other three parts of the Conquest section—on Europe, Africa and the Americas.

While only the Decades of Asia has survived into modern times (the part of the Conquest section devoted to Asia), it is interesting to imagine how different the other works might have been from one another, and where they may have overlapped or connected. We can also use Barros’s tripartite division of Portugal’s colonialist expansion to think about how various kinds of knowledge were crucial for early modern European colonialism.

About this Edition

The source text for this edition can be viewed online at https://digital-archives.sophia.ac.jp/laures-kirishitan-bunko/view/ kirishitan_bunko/JL-1552-KB2-117-48. For the convenience of the reader, the Portuguese text has been segmented into sentences (in its original form, the paragraphs are often very lengthy). The segmentation of the English translation follows the Portuguese text.

First Decade of Asia, Chapter 1 | Primeira Década da Asia, Capitulo I

Asia de Ioam de Barros: Dos Feitos que os portugueses fizeram no descobrimento & conquista dos mares & terras do Oriente

Capítulo primeiro, como os mouros vieram tomar Espanha: & depois que Portugal foy intitulado em Reynos, os Reys delle os lançaram alem mar, onde os foram conquistar, assi nas partes de Africa como nas de Asia: & a causa do título dessa escriptura

Alevantado em a terra de Arabia aquelle grande antechristo Mafamede, quasi nos annos de quinhentos nouenta & tres de nossa redempçam, assi laurou a furia de seu ferro & fogo de sua infernal secta, per meyo de seus capitâes, & calyfas: que em espaço de cem annos, conquistaram em Asia toda Arabia, & parte da Syria & Persia, & em Africa todo Egypto daquem, & dalem do Nilo.

E segundo escreuem os Arabios no seu Larigh, que he hum summario dos feitos que fizeram os seus calyfas na conquista da quellas partes do oriente: neste mesmo tempo, dela se leuataram, & vieram grandes exames delles pouoar estas do ponente a que elles chamam Algarb, & nos corruptamente Algarue dalem mar.

Os quaes a força de armas deuastando & asolando as terras, se fizeram senhores da mayor parte da Mauritania, Tingitania, em que se comprendem os reynos de Fez, & Marrocos: sem ate este tempo a nossa Europa sentir a perseguiçam desta praga.

Pero vindo o tempo ate o qual Deos quis dissimular os peccados de Espanha, esperando sua penitencia acerca das heresias de Arrio, Eluido, & Pelagio de que ella andou muy yscada: (posto que ja per sanctos consilios nella celebrados fossem desterradas,) em lugar de penitencia acresentou outros muy graues & pubricos peccados, & que mais acabaram de encher a medida de sua condenaçam, que a forca feita a Caua filha do conde Iuliam (ainda que esta foy a causa vltima, & accidetal, segundo querem alguns escriptores.)

Com as quaes cousas prouocada a justiça de Deos, vsou de seu diuino & antigo juyzo: que sempre foy castigar pubricos & gerâes peccados, com pubricos & notaueis peccadores, & permitir que hum hereje seja açoute doutro, vingandose per esta maneira de seus imigos per outros mayores imigos.

E como naquelle tempo estes Arabios eram os mais notauees que elle tinha, infestando o imperio Romano & perseguindo sua catholica Igreja: primeiro que per elles castigasse Espanha os quis castigar na sua heresia, acendendo antre elles hum fogo de competencia, sobre quem se assentaria na cadeira do pontificado de sua abominaçam, com este titulo de calyfa, que naquelle tempo era a mayor degnidade da sua secta.

E depois de Arabia, Syria, & parte da Persia, arderem com guerras de confusam aquem perualeceria neste estado, em que morreo grande numero delles, tendo cada parentella enlegido calyfa antre sy: vieram alguns naquella parte interior de Arabia onde esta situa da a cidade Cufa, per concordia de sua cisma babilonica, enleger por calyfa a hum arabio chamado, C,afa: dizendo que a elle pertencia aquelle Pontificado por ser o mais chegado parente de Mafamede: ca elle vinha per linha direita de Abaz seu tio, a linhagem do qual Abaz elles chamam Abazcion.

E porque quando o aleuantaram por seu calyfa, foy com lhe darem juramento que auia de ir destruir o calyfa que emtam residia na cidade Damasco que era dalinhagem a que elles chamam Maraunion, em a qual auia muytos annos que andaua o calyfado per modo de tyrannia mais que per eleiçam, & por isso era esta geraçam muy auorecida antre a mayor parte dos Arabios: ordenou logo este nouo calyfa hum seu parente per nome Abedela benAlle, que com grande numero de gente de cauallo fosse sobre o calyfa de Damasco.

O qual Abedela sendo com este exercito junto do rio Eufrates topou o mesmo calyfa que hya Buscar, que vinha de dar huma batalha a outro calyfa nouamente aleuantado nas partes da Mesopotamia: & rompendo ambos seus exercitos, ouue antre elles huma muy crua batalha em que o calyfa de Damasco foy vencido.

E temendo elle a furia deste seu imigo Abedela, quis se recolher na cidade Damasco de tantos tempos fora senhor: mas os moradores della lhe fecharão as portas sem o quererem receber, com que lhe conueo fugir pera a cidade do Cayro, onde achou pior gasalhado, dizendo todolos cidadões que deos os tinha liurado de hum tam mao homem como elle sempre fora.

Vendoso elle em todalas partes tam mal recibido, ja desemparado dos seus, como homem desesperado do adjutorio delles quis se passar aos Gregos: & indo com hum escrauo seu, foy ter a huma Ilha onde sendo conhecido o mataram, no qual acabaram todolos calyfas de Damasco, Abedela seu imigo tanto que venceo & soube quam mal recibido hera dos proprios feus, sem o querer mais perseguir foy se dereitamente a Damasco: & tomada pose da cidade, a primeira cousa que fez, foy mandar defenterrar o calyfa Yazit que era dos primeiros que ali foram daquella linhagem Maraunion, auendo ja muytos annos que era falecido, os hosos do qual com hum aucto publico manduo queimar.

Porque sendo Docem neto de Mafamede seu legislador, filho de sua filha Aixa, & de Alle seu sobrinho, direitamente en legido por calyfa como fora seu pay: elle. Yazat nam somente lhe nam quisera obedecer, mas ainda tene modo como Docem fosse morto, tudo por elle Yazit se leuantar com o calyfado, o qual pesuyo tyrannicamente, E assi todolos de sua linhage per muytos tempos.

E nam contente este Abedela com tomar tal vingança deste Yazit, geralmente a toda sua parentela mandaua matar com mil generos de tormentos, & lançar seus corpos no campo âs feras & aues delle: dizendo serem todos efcomungados & dignos de nam ter sepultura, pois eram do sangue da quelle pessimo homem que mandou derramar o do justo Docem, vngido naquella dignidade de calyfa per o testamento de seu auo Mafamede.

Da furia & fogo das quaes cruezas que este Abedela fazia, saltou huma faisca que veo abrasar toda Espanha, & o caso procedeo per esta maneira. Antre alguns desta linhagem Marauniom que este capitam Abedela perseguia, auia hum hômem poderoso chamado AbedRamon filho de Mauhyam, & neto de Doxon, & bisneto de Abbedelmalc: o qual auo & bisauo em tempo passado foram tambem calyfas daquella cidade Damasco.

E vendo elle a perseguiçam de sua linhagem & as cruezas que Abedela nella fazia, temendo receber outros taes em sua pessoa: recolheo pera si os mais parentes que pode, com outra gente solta, cuja vida era andar em guerras & roubos, & feito hum grande excercito de gente por autorizar sua pessoa, meyo fogindo veo ter a estas partes do ponente.

Onde, assi por ser da linhagem dos calyfas de Damasco, como por ser homem valeroso & caualeiro de sua pessoa foy muy bem recebido, & concorreo a ella tanta gente arabia da que ja ca andaua nestas partes dos Algarues dalem mar, que vendose tam poderoso em gente & opiniam de secta: Tomou ousadia a se intitular com nouo nome chamandose principe dos Crentes nesta palaura arabia Miralmuminim, a que nos coruptamente chamamos Miramulim, & isto quasi em opprobio & reprouaçam dos calyfas da linhagem de Abaz que nouamente foram leuantados na Arabia por cuja causa elle se desterrou daquellas partes de Damasco.

E nam se contentando ainda com este nouo & soberbo nome, fundou a cidade Marrocos pera cadeira de seu estado & metropoli daquella regiam (posto que algumas cronicas dos arabios querem que a edificou Iosep filho Iestim, & outros que outro principe, como veremos em a nossa geographia.)

A causa da fundaçam da qual cidade, dizem alguns delles que nam foy tanto por gloria que este AbedRamom teue da memoria do seu nome: quanto em reprouaçam doutra que ouuio dizar que fundaua o calyfa Bujafar irmão & sucessor do calyfa Cafa, que foy causa de se elle vir a estas partes.

A qual cidade que este Bujafar fundou tambem, era pera cadeira onde auia sempre de residir o seu pontificado de calyfa: & he aquella a que ora os mouros chamam Bagodad, situada na prouincia de Babilonia nas correntes do rio Eufrates.

E segundo escreuem os Parseos & Arabeos no seu Larigh que alegamos, o qual temos em nosso poder em lingua Parsea: foy esta cidade Bagodad fundada per conselho de hum astrologo gentio per nome Nobach, & tem por ascendente o signo Sagitario, & acabouse em quatro annos, & custou dezoito contos douro, da qual em a nossa geographia faremos mayor relaçam.

Pois estando este nouo Miralmuminim com potencia em estado & numero de gente, feito outro Nabuchodonosor pera castigo do pouo de Espanha: totalmente seu filho Vlid que o sucedeo em nome, & poder se fez senhor della, per Mussa, & per outros seus capitães, em tempo del Rey dom Rodrigo, o derradeiro dos Godos.

Mas aprouue a diuina misericordia que este açoute de sua justiça, tornasse logo atras daquelle impeto de vitorias, que per espaço de trinta meses teue: dando animo & fauor aquelle bemauenturado Principe dom Pelayo, com que logo começou ganhar as terras que ja estauaom subditas ao ferro & cruezas destes alarues.

E procedendo estas vitorias em recobrar Espanha per discurso de trezentos quorenta & tantos annos: vieram ter a el Rey dom Affonso o sexto deste nome, dalcunha o brauo que tomou Toledo aos mouros.

O qual querendo satisfazer aos seruiços & ajudas que lhe o conde dom Anrique nesta guerra dos mouros tinha feito & dado, nam achou cousa mais digna de sua pessoa, nem de mayor galardam, que aceitallo por filho, dandolhe por molher a sua filha dona Tareija: & em dote, todalas terras que naquelle tempo eram tomadas aos mouros nesta parte da Lusitania que ora he Reyno de Portugal, com todalas mais que elle podesse conquistar delles. Em que entrauaom algumas de Andaluzia, porque em todas estas elle & seu filho el Rey dom Afonso Anriquez verteram seu sangue por as ganhar das mãos & poder dos Mouros: (como se vera em a outra parte da nossa escriptura chamada Europa.)

O qual dote, & herança, parece que foy dado com tal bençam per este catholico Rey dom Afonso: que todolos seus descendentes que a herdassem, sempre teuessem continua guerra com esta perfida gente dos Arabios.

Porque começando deste tempo té o presente, que he discurso de quatrocentos & tantos annos de idade deste Reyno de Portugal, depois que apartado da coroa de Espanha teue este nome: assi parmaneceo em continua guerra destes infieis, que com verdade se pode dizer por elle, ter vestido mais armas que pelotes.

Donde podemos afirmar que esta casa de coroa de Portugal, esta fundada sobre sangue de martyres, & que martyres a dilatam, & estendem per todo o vniuerso: se este nome podem merecer aquelles que militando pola fee offerecem suas vidas a Deos em sacrficio, & dotam suas fazendas a sumotuosos templos que fundaram.

Como vemos que fez el Rey dom Afonso Anriquez primeiro, fundador desta casa real, & o conde dom Anrique seu padre & toda a nobreza & fidalguia que os seguia nesta confissam & defensam da fee, da qual verdade sam testemunho muy dotados & magnificos templos deste Reyno.

E passados os primeiros annos de infancia delle, que foy todo o tempo que esteue no berço em que naceo, limitado na costa do mar Oceano (porque o mais do sertam da terra, ficou na coroa de Castella, & a ella lhe nam coube mais em sorte nesta nossa Europa:)

Todo o trabalho daquelles Principes que entam o gouernauam, foy alimpar a casa desta infiel gente dos Arabeos que lha tinham occupada do tempo da perdição de Espanha, té totalmente a poder de ferro os lançarem alem mar, com que se intitularam Reys de Portugal, & do Algarue.

E assi estaua limpa delles no tempo del Rey dom Ioam o primeiro, que desejando elle derramar seu sangue na guerra dos infieis, por auer a benção de seus auôos, esteue determinado de fazer guerra aos Mouros do Reyno de Gra[na]da: & por algus inconuenientes de Castella, & assi por mayor gloria sua, passou alem mar em as partes de Africa, onde tomou aquella Metropoly Cepta cidade tam cruel competidor de Espanha, como Cartago foy de Italia.

Da qual cidade se logo intitulou por senhor, como quem tomaua posse daquella parte de Africa, & [d] eixaua porta aberta a seus filhos & netos pera irem mais auante.

O que elles muy bem compriram, porque nam somente tomaran cidades villas & lugares, nos principaes portos, & forças dos Reynos de Fez, & Marrocos, restituindo a Igreja Romana a jurisdição que naquellas partes tinha perdida depois da perdiçam de Espanha, como obedientes filhos & primeiros capitães polla fee nestas partes de Africa: mas ainda foram despregar aquella diuina & real bandeira da milicia de Christo (que elles fundaram pera esta guerra dos infieis) nas partes Orientaes da Asia em meyo das infernaes mesquitas da Arabea, & Persia, & de totolos pagôdes da gentilidade da India daquem, & dalem do Gange: partes onde (segundo escriptores Gregos & latinos) excepto a illustre Semirames, Bacho, & o grande Alexandre, ninguem ousou cometer.

Com as quais vitorias que os Reys deste Reyno ouueram nestas tres partes da terra, Europa, Africa, & Asia, ganhando Reynos & estados, acrescentaram sua coroa com nouos, & illustres titulos que lhe deram do que alguns Principes desta nossa Europa tem nos estados de que se intitulam, dos quaes esta em posse esta barbara gente de mouros sem os poderem vindicar per lei de armas.

E os Reyes deste Reyno, sendo senhores do Reyno de Ormuz, cujo estado tem boa parte & amilhor da terra maritima da Arabia, & da Persia, & senhores do Reyno de Cambaya com lhe ter tomado o maritimo delle, & senhores do Reyno de Goa, com as terras, & ilhas a ella adjacentes, & senhores da requissima Malaca situada na Aurea Chersoneso tam celebrada dos geographos, & fenhores das ilhas Orientaes de Maluco, Banda, &c. somente se intitulam por Reys de Portugal, & dos Algarues daquem & dalem mar, senhores de Guine, & da conquista, nauegaçam, & comercio, da Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, & India: como se estoutros Reynos & senhorios nomeados, nam se gouernassem per suas leyes, & ordenações, & lhe nam pagassem tributos & rendas, & elles lhe name tiuessem o pescoço debaixo do escabello de seus pes.

Mas como de cade huma destas partes em seu lugar mais copiosamente fazemos relação, ao presente ([d] eixadas ellas) pera se milhor entender o fundamento desta nossa Asia, conuem que saibamos como no titulo da Real coroa destes Reynos, se comprendem tres cousas distintas huma da outra: posto que entre si sejam tam correlatiuas, que huma nam pode ser sem adjutorio da outra, comunicandose pera sua conseruação.

Quanto a parte da conquista que he propria da milicia, esta porque foy em todalas partes da terra, fazemos della quatro partes de escriptura: (posto que em seys em a nossa geographia diuidamos todo o vniuerso.)

Aa primeira parte desta milicia chamamos Europa, começando do tempo que os Romanos conquistaram Espanha na qual guerra os Portugueses perfeitos illustres teueram gram nome acerca delles: & d[a]hy viremos fazendo discurso per os tempos té o conde dom Anrique, & per el Rey dom Afonso Anriquez & seus sucessores, Aa seguda parte chamamos Africa: cujo principio he a tomada de Cepta.

A terceira que he esta que temos antre as mãos o seu nome he Asia: por tratar do descobrimento & conquista das terras & mares do Oriente, começando do tempo do Infante dom Anrique, que foy o primeiro inuentor desta milicia Austral & Oriental.

E a quarta (porque assi chamamos em a nossa Geographia a terra do Brasil) auera nome Sacta Cruz: nome proprio posto per Pedrealuarez Cabral quando o anno de mil & quinhentos indo pera a India a descobrio, & aqui tera seu principio.

E de todas estas quatro partes de milicia, esta Oriental fenece ao presente no anno de mil & quinhentos & trinta & noue, onde acabamos de cerrar numero de quorenta liuros, que compõem quatro Decadas, que quissemos tirar a luz, por mostra do nosso trabalho: té que venha outro cursa de annos, que seguira a estes na mesma ordem de Decadas, dandonos Deos vida & lugar pera o poder fazer.

Quanto ao titulo da nauegaçam, a este respondemos com huma vniuersal Geographia de todo o descuberto: assi em graduaçam de taboas como de comentario sobrellas, aplicando o moderno ao antigo, a qual nam sofre compostura em lingoagem, & por isso hira em latim.

A parte do comercio, porque elle geralmente andaua per todalas gentes sem ley nem regras de prudencia, somente se gouernaua & regia pello impeto da cobiça que cada hum tinha: nos o reduzimos & possemos em arte com regras vniuersaes & particulares, como tem todalas sciencias & artes actiuas pera boa policia.

Onde particularmente se veram todalas cousas de que os homeens tem vso: ora sejam naturaes, ora artficiaes, com a natureza & qualidade de cada huma dellas (segundo o que podemos alcançar) com as mais partes de pesos medidas, & cetera, que a esta materia conuem.

E Deos he testemunha que em cada huma desta tres partes, Conquista, Nauegaçam, & Comercio, fizemos a diligencia possiuel a nos: & mais do que occupaçam do officio & profissam de vida nos tem dado lugar.

E quando em alguma dellas desfalecermos na diligencia & eloquencia que conuinha a verdade, & magestade da mesma cousa: esse Deos onde estão todalas verdades, ordene que venha alguem menos occupado, & mais doucto do que eu sou, pera que emende meus defeitos: os quaes bem se podem recompensar com a zelo & amor que tenho a patria, por tirar a infamia dalgumas fabulas & ignorancias que andam na boca do vulgo, & per papeis escriptos dinos de seus auctores.

[D]eixados meus defectos, & assi esta geral preparaçam de toda a obra quasi em modo de argumento & diuisam della: venhamos âs causas que o Infante dom Anrique teue pera tomar tam illustre empresa, como foy o descobrimento & conquista que deu fundamento a esta nossa Asia, dos feitos que os Portugueses fizeram no descobrimento & conquista das terras & mares do Oriente, como diz o titulo desta nossa escriptura.

First Decade of Asia, Chapter 1

Asia by Joao de Barros: on the achievements by the Portuguese in their discovery and conquest of the oceans and lands in the East.First chapter, on how the Muslims came to conquer Spain; and on how, after Portugal became a kingdom, its kings drove the Muslims overseas, both to parts of Africa and to parts of Asia, where the Portuguese kings went to conquer them; and on the reasons why this book has the title it has.

When the great antichrist Muhammad emerged in the land of Arabia, sometime around the year 593 of our redemption, he adorned the conquering fury of his infernal sect with fire and iron by deploying his captains and caliphs; in the space of a hundred years, they conquered in Asia all of Arabia, as well as parts of Syria and Persia, and in Africa all of Egypt around the Nile.

During that same period, according to what the Arabs write in their Larigh (which is a summary of their caliphs’ deeds during their conquest of those parts of the East), great swarms of Arabs came from those parts of the East to populate these lands of the West which they called “Algarb”, and which we mistakenly call “overseas Algarve”.

They became the lords of most of Mauritania and Tingitania through their use of arms, destroying and laying waste to the lands, where the kingdoms of Fez and Morocco lie: all these events happened without our Europe feeling any of the effects of this plague.

However, the time came for God to undo the sins of Spain—an expected punishment for the heresies that had had their grasp on Spain for a long time, such as those of Arius, Helvidius, and Pelagius (even though those heresies had already been condemned by holy councils). Instead of repenting for its sins, Spain added other, more egregious and public sins to its record; these added to the measuring cup by which God assessed Spain’s need for punishment, and included the harm done to Cava, daughter of Count Julian (even if this harm was ultimately accidental, as some writers claim).

All of this brought God’s justice onto Spain, where He employed His divine and ancient reasoning, which was always to punish public and widespread sin by deploying other public and notorious sinners, thus making one heretic the whip that punishes the other, and in this way taking revenge on some of His enemies by deploying other and greater ones.

Since, at that time, God’s most notorious enemies were the Arabs, who infested the Roman Empire and persecuted God’s Catholic Church, He wished to punish them for their heresies first before using them to punish Spain. So he kindled the fire of competition over who would sit on the pontifical throne of their abominable heresy, that is who would bear the title of caliph, which was, at that time, the sect’s greatest dignitary.

And thus Arabia, Syria, and part of Persia burned in confusing wars over who was to prevail, which caused the death of many. The wars resulted in each family group electing their own caliph amongst themselves. Some of these came to the interior of Arabia, where the city of Kufa lies, and agreed to elect an Arab man called C’afa in order to overcome their Babylonian schism. They said that the pontificate belonged to C’afa because he was Muhammad’s closest relative: through his uncle Abaz, C’afa was a direct descendant from Muhammad’s line, a line which they called Abazcion.

C’afa was proclaimed caliph as soon as he swore that he would destroy the caliph who dwelled in the city of Damascus, who was from the so-called lineage of Maraunion. This lineage had ruled that caliphate [of Damascus] for many years by tyranny rather than election, and that is the reason why this generation was so covetous in comparison to the majority of Arabs. Since those were the conditions of his being proclaimed Caliph of Kufa, the new caliph sent a relative of his called Abdullah bin Alle to attack the Caliph of Damascus with a great army of mounted soldiers.

Abdullah, who was with his army close to the Euphrates river, stumbled upon the caliph he was searching for, who was himself returning from a skirmish with yet another caliph who had emerged somewhere in Mesopotamia. Abdullah’s army and the Caliph of Damascus’s army collided in a very crude battle, which the Caliph of Damascus lost.

Fearing his sworn enemy Abdullah’s fury, the Caliph [of Damascus] sought to retreat into the city of Damascus that he had lorded over for so long, but its inhabitants closed their doors to him as they did not want to host him there; he then fled to the city of Cairo, where he was even more poorly hosted, as all the inhabitants claimed that they had been delivered from a very evil man—just like the Caliph of Damascus had always been.

Seeing that he was not welcomed anywhere, and having lost his supporters, the Caliph desperately resorted to the Greeks’ aid: he went there [to Greece] with a slave of his, arriving on an island where they recognized who he was and killed him, thus ending all caliphs of Damascus. Knowing that the Caliph of Damascus was not welcome among his own people, his enemy, Abdullah, as soon as he had won the battle against him, decided not to chase after the Caliph but to go directly to Damascus himself. After Abdullah took control of the city, the first thing he ordered was for the late Caliph Yazit to be exhumed so that his bones could be burned in a public act; Yazit was one of the first of the Maraunion lineage and had died many years before.

Abdullah did so because, years before, Yazit had chosen not to obey Doxem, Muhammad’s legislator and grandson (the son of his daughter Aixa and of Alle his nephew) and the rightfully elected caliph. Not only had Yazit decided not to obey Doxem, but he had even ordered his death, all so that Yazit himself could become the caliph instead of Doxem, the rightful heir to the caliphate as his father had been. Yazit then ruled the caliphate tyrannically, and so did every one of his descendants for centuries.

Abdullah, unsatisfied with his posthumous revenge on Yazit, ordered all of Yazit’s relatives and extended family to be tortured to death and their bodies scattered on the fields for the wild beasts and birds. He also ordered them to be excommunicated and not granted a proper burial, because they had the same blood of the rascal who had spilled the blood of the honorable Doxem, whom Muhammad himself had anointed caliph in his will.

From the same fire and fury that Abdullah’s cruelties began leapt a spark which would come to burn all of Spain. This is how it happened: among those of the Maraunion lineage whom Abdullah was persecuting, there was a powerful man named Abed Ramon, son of Mauhyam, grandson of Doxon, and great-grandson of Abdullmalec, whose grandfather and great-grandfather had been caliphs of Damascus.

Abed Ramon, seeing how Abdullah persecuted his line and the cruelties he carried out against it, and also fearing that he himself would be subject to those same cruelties, he gathered as many relatives as he could and some wandering people whose lives were dedicated to wars and ransacking. Having gathered a great army to empower himself, he then escaped to those lands to the West.

There he was welcomed because he from the lineage of the caliphs of Damascus, and also because he was brave and chivalrous. Many people from Arabia joined him, people who had already been living in those parts across the sea from Algarve. Noticing how powerful he was because he had many followers and was well regarded by those who shared his beliefs, he dared to name himself “the Prince of the Believers”, with the Arabic word “Miralmuminim”, which we erroneously say “Miramulim”. He did this almost in spite and rejection of the caliphs of the Abaz lineage, on whose account he had been driven out of Damascus into exile, and who were now once again raising their armies in Arabia to fight him.

Not fully satisfied with his new and lofty name, Abed Ramon founded the city of Morocco, making it the seat of his estate and the metropolis of that region (despite some Arab chroniclers saying that the city was founded by Joseph, son of Jestim, and others saying that another prince founded it, as we will see in our Geography).

Some of their historians claim that the reason why that city was founded was not so much for the glory that Abed Ramon wanted for his name, but rather to compete with another city he heard had been founded by Caliph Bujafar, the brother and successor of the Caliph C’afa, who was the original reason for Abed Ramon’s removal to these parts.

The city that Bujafar founded was also intended to be the seat of his own pontifical caliphate; it is the city that Muslims today call Baghdad, which lies in the province of Babylon on the banks of the Euphrates.

And as the Persians and Arabs write in their aforementioned Larigh, of which we have a copy in the Persian language, the city of Baghdad was founded on the counsel of a gentile astrologer whose name was Nobach. The city was founded under the sign of Sagittarius and the founding took four years and cost eighteen counts of gold (we will further expand the account of this in our Geography).

Since this new Miralmuminim had both the powers of an organized kingdom and the support of numerous peoples, as if he were another Nebuchadnezzar, he caused the plight of the people of Spain. His son Ulid, who succeeded him, was able to completely rule over Spain with the aid of Mussa and his other captains. All of this took place during the time of King Rodrigo, the last of the Goths.

But praised be the Divine Mercy that this strike of punishment and justice that befell Spain would be soon followed by many Spanish victories, which happened over a period of thirty months. The Divine Mercy bestowed courage upon and favored that blessed Prince Pelayo, who began to win back the lands that were subjected to the sword and the cruelties of those brutes.

These victories for the recovery of Spain took place over more than 340 years. They eventually ended in the reign of King Afonso VI, the Brave, whose name stemmed from having won Toledo back from the Muslims.

Afonso VI, who wanted to reward the services that Count Henrique had rendered him in his wars against the Muslims, thought it was worthy and most appropriate to accept Henrique as his own son by giving him his daughter Lady Tareija in marriage. The dowry was all the lands that, at that time, belonged to the Muslims in the part of Lusitania which is now the Kingdom of Portugal, and whichever other lands he could win back from the Muslims, including some in Andalusia. There, Henrique and later his son, the King Afonso Henrique, spilled their own blood to recover the lands from the hands and the rule of the Muslims (as we will see in another work of ours called Europe).

This dowry was given with the blessing of that very Catholic king Afonso VI, but with one condition: that all of Henry’s descendants who inherited the lands given as the dowry would always fight against the perfidious Arab peoples.

This is why, from that time until now, a period of more than 400 years marking the age of the Kingdom of Portugal (it received this name after being separated from the crown of Spain), Portugal has remained in a perpetual state of war against the infidels, which is why we can truthfully say that the Kingdom of Portugal has borne arms more often than robes during its existence.

And thus we can also affirm that the Portuguese crown was founded on the blood of martyrs, and that these martyrs have expanded its renown throughout the whole of the universe; that is, if we consider them deserving of the name “martyr” who willingly gave their lives in sacrifice for their faith in God, and who founded sumptuous temples in their lands in honor of Him.

This is exactly what we saw King Afonso Henrique I, the founder of this royal house, do; as well as Count Henrique his father, and all the noble and important people who followed them in their practice and defense of the Catholic faith. And the many magnificent and well-endowed temples that exist in this kingdom stand as witnesses to these truths.

And the first years of the kingdom’s infancy passed, during which the Kingdom lay in the cradle where it was born, limited as it was by the Ocean sea to the west (because the most interior part of the land remained with the crown of Castile and to which nothing else belonged in this Europe of ours):

All the toil of those princes who ruled over the Kingdom of Portugal was to enlarge it at the expense of the Arab peoples who had occupied it during Spain’s sinful times, until they [the Portuguese] were able to completely drive the Arabs overseas by their military power, which is when they started to title themselves the Kings of Portugal and Algarve.

And thus this land was free from the Arabs by the time of King John I, who, wishing that he could spill his own blood in the war against the infidels, and since he had been blessed by his forefathers, was determined to wage war against the Muslims of the Kingdom of Granada. And because of some inconvenient dealings with Castile, and because he wished to attain even more glory for himself, he went overseas into parts of Africa, where he conquered the metropolis Ceuta, as cruel a rival city to Spain as Carthage had been to Ancient Rome.

He named himself Lord of Ceuta, and with that act took over that part of Africa and left the door open for his sons and grandsons to go even further.

His sons followed his steps very well. They not only conquered many cities, villages, and places from the main ports and armies of the kingdoms of Fez and Morocco, restoring to the Catholic Church its jurisdictions in those lands that had been lost after Spain’s punishment, but they were also obedient sons and captains of God’s faith in those parts of Africa. Moreover, they went all the way to the eastern parts of Asia to fly the divine and royal flag of the Order of Christ (an order founded to wage war against the infidels) among the infernal mosques of Arabia, Persia, and among all the temples of the pagans of India up to and beyond the Ganges. They reached parts of the Orient which, according to Greek and Roman writers, nobody had dared reach before, except for the illustrious Semiramis, Bacchus, and Alexander the Great.

With these victories achieved by the kings of this kingdom in the three parts of the globe—Europe, Africa, and Asia—conquering kingdoms and estates, they have expanded their crown with the acquisition of new and illustrious titles. Although some other princes in this Europe of ours possess similar titles, their namesake territories are still in the possession of the barbarous Muslim people, which those princes cannot recover by waging war.

Thus the kings of this kingdom are also lords of the Kingdom of Ormuz, of which they possess the greater part, and which has the best maritime land in Arabia and Persia; lords of the Kingdom of Cambaya, having conquered its maritime access; lords of the Kingdom of Goa, with its adjacent lands and islands; lords of Malacca, which lies in the Golden Chersonese, a region so admired by ancient geographers; and lords of the Eastern Islands of Maluku and Banda. However, they style themselves only: “Kings of Portugal and Algarve (Before and Beyond the Sea), Lords of Guinea, and [Lords] of the Conquest, Navigation, and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, and India”. They bear only these latter titles, as if the aforementioned kingdoms and lordships were not governed by Portuguese laws and ordinances, and as if those places did not pay taxes and send revenues to Portugal, and as if the Portuguese kings did not have the kingdoms’ necks under their little wooden bench where the Portuguese rest their feet.

But as we narrate a more copious account of each of those places in this work, we leave them aside for now. It is more imperative for our better understanding of the foundations of this Asia of ours that we know how the title of the royal crown of the kingdoms of Portugal and Algarve is composed of three very different things; though distinct, they are related to one another, and one cannot exist without the aid of the other, as their survival is connected.

A primeira he conquista, a qual trata de milicia, a segunda nauegação, a que responde a geographia, & a terceira comerçio que conuem a mercadaria: das quais partes querendo nos escreuer soccessiuamente como ellas se foram adquerindo & ajuntando a coroa deste Reyno, em lugar & tempo, por nam confundir os meritos de cade huma das matereas, com adjutorio diuino que pera isso imploramos, per este modo trataremos dellas.

The first one is conquest, which relates to matters of war; the second is navigation, which corresponds to geography; and the third is commerce, which encompasses the trade of goods. We wish to write about each of these parts so as to accompany how they came to be part of this kingdom’s crown over the years, placing each in its proper place and time. We deal with these subjects in this fashion to avoid a confusion between the merits of each; with divine help, we will divide the subjects in this way.

Concerning the part of conquest which concerns war: since these events happened in all parts of the Earth, we will divide the subject of war into four parts in this book (even though we divided the world into six parts in our Geography).

We call “Europe” the first part of these writings concerning war, beginning with the times when the Romans conquered Spain, a time of wars in which the illustrious and perfect Portuguese people participated. From there, we will course through time until we come to Count Henrique and King Afonso Henrique and his successors. We call “Africa” the second part, which begins with the taking of Ceuta.

The third part, which we have in our hands now, is called “Asia”: because it covers the discovery and conquest of the lands and seas of the Orient, beginning during the time of the Prince Henrique, who was the first creator of the Southern and Eastern Army.

And the fourth part is called “Holy Cross” (because this is how we called the land of Brazil in our Geography), which is the name that Pedro Alvarez Cabral gave to that land when he discovered it in the year 1500 while sailing to India.

And of the four parts concerning war, this volume concerns itself with the oriental one, up to the present year—1539. We have just finished forty books, covering four decades, which we wished to bring forth to show the work we have done; in the course of the coming years, they will be followed by another set of volumes covering the following decades, if God gives us life and a place to do so.

As for the subject of navigation, we responded to this topic by writing a universal Geography, covering all that has been discovered: it contains scaled charts of the world with commentary on each part, adding the modern discoveries to the ancient ones. This work is written in Latin, for the subject is improper for Portuguese.

The third part, which concerns commerce, because it is so widespread an activity—even among peoples with neither laws nor rules of conviviality, who are governed and ruled by each individual’s impetuous greed—we summarized it and put it in the form of a treatise with universal and particular rules, as is done with all the sciences and arts which contribute to good behavior.

It is in this third and last part that one will see all things that are useful to humankind, both natural and artificial; it will cover each thing’s nature and quality (according to what we could find), its weight, measurements, et cetera—all that pertains to this subject.

And God is our witness that in each of these three parts, Conquest, Navigation, and Commerce, we have diligently done what we were able to do, and much more than what our office and task demands and allows us to do.

And if we falter in the diligence or eloquence necessary for the truth and majesty in each of those subjects, may God, in whom all truth resides, command someone less busy and more learned than I am to amend my mistakes. Such mistakes, however, are excused by the zeal and love I have for this country and by the fact that this work will restore the truth to some deceitful stories that are spread by popular word of mouth and by other works by certain authors.

Leaving my faults aside and this overview of the whole work and its argument, we now come to the reasons that Prince Henrique had to carry out this enterprise, that is, the discovery and conquest that gave this Asia of ours its foundation—the deeds of the Portuguese in the discovery and conquest of the lands and seas of the Orient, as stated in the title of this work.