Introduction: So that rivals do not slander this collection of jokes for its inelegance | Ne Aemuli Carpant Facetiarum Opus, Propter Eloquentiae Tenuitatem

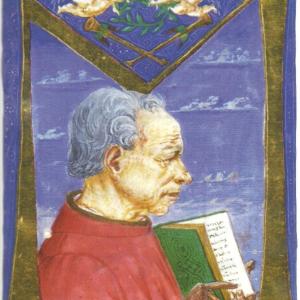

Poggio Bracciolini, detail from Vatican Urb.Lat.224 f.68r [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

Gian Francesco Poggio Bracciolini (commonly referred to as simply Poggio Bracciolini) was born in Terranuova (Tuscany) in 1380. He died in Florence in 1459 at the age of seventy-nine. During his long life this early and important humanist had an equally long career at the Papal curia. In the service of a sequence of popes he lived in Rome, travelled with the papal court all across Italy and the rest of Europe.

Poggio produced a wide range of writing during his career (his collected works span four substantial volumes). He often worked in the dialogue form or wrote speeches, but he also wrote history. He was an avid book hunter and a skilled scribe.

Through his texts we also meet a very polemical man, who seems to get into fights with many of his contemporaries, the most famous of which is his conflict with another of the humanist greats, Lorenzo Valla. The collections of jokes and stories known today as the Facetiae, but which Poggio himself preferred to refer to as Conversations ( Confabulationes), certainly contains a polemical edge. While Poggio’s invectives are violently polemical and often personal, his Facetiae are more mildly polemical in the satirical tradition. The Facetiae as it is preserved consists of 273 jokes/stories ranging from just a few lines to a page in length. The collection also has an introduction and a type of conclusion. The short selection presented here contains a few rowdy jokes that poke fun at crude people and priests or monks, and another few stories with witty remarks from historical or contemporary characters. For readers interested in the obscene elements in the Facetiae, Poggio’s work can be compared to Beccadelli’s The Hermaphrodite, which offers another contemporary source of obscenity, but one based on very clear ancient models (among others Catullus). The selection shows that Poggio seems to have put his main focus on witticism when writing the stories; whether rude tales or short adventures of cooks, soldiers or even the famous Dante, the punchline seems almost always to be some sort of turn of phrase or wry observation (although this might not always be completely obvious to a modern reader).

As for Poggio’s motive with writing the Facetiae, he phrases it best himself in this text, which served as an introduction to the collection, a defense of the Facetiae and a declaration of its purpose.

Introduction to the Source

The Facetiae seems to have had immediate success. The collection as we now know it was composed between 1452-53, but Poggio had by then been working on versions of it (some of which had been in circulation) from as early as 1438. Over fifty manuscripts containing the text are preserved to this day. The Facetiae was also printed early and repeatedly, first appearing in this form around 1470. Another testimony to the popularity of the text is the fact that Poggio’s jokes or ‘conversations’ were translated to several other languages, either the entire collection (to Italian and French at the end of the fifteenth century) or individual stories, which were mixed into the different Aesop collections circulating during this period. Herein lies somewhat of an irony, since Poggio himself in the introduction to the Facetiae seems to indicate that the object of writing them is to write stories in Latin that are usually told in the vernacular languages.

About this Edition

The translation is based on the text as it appears in the Basel 1538 edition of Poggio’s collected work available on Google Books, with a slight update to punctuation and orthography (for instance, ij is represented as ii). No emendations or other corrections have been made by the translator. Older versions of the text contain a few variants and some obvious errors, but in general the tradition seems quite stable (see, for example, an early print from 1471; or the fifteenth-century manuscript in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 8770A).

Further Reading

Kallendorf, Craig. “Poggio Bracciolini” in Oxford Bibliographies. DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195399301-0095.

- Craig Kallendorf’s article in Oxford Bibliographies is a good starting point for researching Poggio. The article contains information about relevant editions, translations, and research.

Pittaluga, Stefano, ed. Facéties = Confabulationes: Édition bilingue. Translated by Etienne Wolff. Bibliothèque italienne. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2005.

- The most recent critical edition of the Facetiae.

Beccadelli, Antonio. The Hermaphrodite. Edited and translated by Holt Parke, I Tatti Renaissance Library 42, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Another example of obscene elements in Renaissance Latin (also contains letters exchanged between Beccadelli and ` Bracciolini).

Gordon, Phyllis W. G., ed. Two Renaissance Book Hunters: The Letters of Poggius Bracciolini to Nicolaus de Niccolis. New York: Columbia University Press, 1974.

- This letter exchange shows the scholarly side of Poggio.

Bracciolini, Poggio. The Facetiae of Giovanni Francesco Poggio Bracciolini. Translated by Bernhardt J. Hurwood. New York: Award Books, 1968.

- This is apparently an earlier translation of the Facetiae (I was not, however, able to consult this book for the present translation).

Introduction: So that rivals do not slander this collection of jokes for its inelegance | Ne Aemuli Carpant Facetiarum Opus, Propter Eloquentiae Tenuitatem

Introduction

Multos futuros esse arbitror qui has nostras confabulationes, tum ut res leves et viro gravi indignas reprehendant, tum in eis ornatiorem dicendi modum et maiorem eloquentiam requirant. Quibus ego si respondeam, legisse me nostros Maiores, prudentissimos ac doctissimos viros, facetiis, iocis et fabulis delectatos, non reprehensionem, sed laudem meruisse, satis mihi factum ad illorum existimationem putabo.

Nam quid mihi turpe esse putem hac in re, quandoquidem in ceteris nequeo, illorum imitationem sequi, et hoc idem tempus quod reliqui in circulis et coetu hominum confabulando conterunt, in scribendi cura consumere, praesertim cum neque labor inhonestus sit, et legentes aliqua iucunditate possit afficere? Honestum est enim ac ferme necessarium, certe quod sapientes laudarunt, mentem nostram variis cogitationibus ac molestiis oppressam, recreari quandoque a continuis curis, et eam aliquo iocandi genere ad hilaritatem remissionemque converti. Eloquentiam vero in rebus infimis, vel in his in quibus ad verbum vel facetiae exprimendae sunt, vel aliorum dicta referenda, quaerere, hominis nimium curiosi esse videtur. Sunt enim quaedam quae ornatius nequeant describi, cum ita recensenda sint, quemadmodum protulerunt ea hi qui in confabulationibus coniiciuntur.

Existimabunt aliqui forsan hanc meam excusationem ab ingenii culpa esse profectam, quibus ego quoque assentior. Modo ipsi eadem ornatius politiusque describant, quod ut faciant exhortor, quo lingua Latina etiam levioribus in rebus hac nostra aetate fiat opulentior. Proderit enim ad eloquentiae doctrinam ea scribendi exercitatio. go quidem experiri volui, an multa quae Latine dici difficulter existimantur, non absurde scribi posse viderentur, in quibus cum nullus ornatus, nulla amplitudo sermonis adhiberi queat, satis erit ingenio nostro, si non inconcinne omnino videbuntur a me referri.

Verum facessant ab istarum Confabulationum lectione (sic enim eas appellari volo) qui nimis rigidi censores, aut acres existimatores rerum existunt. A facetis enim et humanis (sicut Lucilius a Consentinis et Tarentinis) legi cupio. Quod si rusticiores erunt, non recuso quin sentiant quod volunt, modo scriptorem ne culpent, qui ad levationem animi haec et ad ingenii exercitium scripsit.

Introduction

I think there will be many who will condemn these conversations of ours, either because they are not serious and unworthy of a dignified man, or because they are in need of a more embellished mode of speech and more eloquence. But if I reply that I have read our forefathers—those wise and learned men who found delight in jokes, jests, and stories—I think that I will earn praise, not reprehension, since I have done enough to gain their appreciation.

For why should I consider it a shameful thing to follow their models in this area, (since I am not able to do so in others). While others waste time conversing in their social circles and groups, I make an effort to write, and especially since it is no dishonest work and can bring the readers some joy. For it is a noble and almost a necessary thing to restore our minds that are oppressed by so many thoughts and troubles (the wise ones certainly approve of this), and to sometimes turn them from constant worry to cheerfulness and relaxation with the genre of jokes. However, to seek eloquence in these low matters, which are represented either word-for-word, or as jokes, or reported as the sayings of somebody else, would seem to be a bit too much for a diligent man. There are indeed some things which cannot be portrayed in a more embellished manner, since these things should be recounted in the same way as they were told by those who had these conversations.

Some will perhaps think that my excuses derive from a lack of skill, and I agree with these people. I really encourage them to write similar things in a more embellished and refined way, so that the Latin language of our time may be richer even where these very light matters are concerned. For the practice of writing these stories will benefit the study of eloquence. Indeed, I wanted to examine whether many of these things that are thought difficult to express in Latin, could be regarded as possible to write down in a non-absurd way. These things cannot be combined with embellishment and high style, so it will be enough as far as my ability is concerned if people think that I have not told the stories in a completely inelegant way.

Truly, they who appear as overly strict censors or bitter critics may avoid reading these Conversations (for this is what I want them to be called). For I wish them to be read by elegant and refined people (as Lucilius was by the Consentians and the Tarentines). If they should be too unsophisticated, I do not object to their thinking what they want, as long as they do not blame the author, who wrote this to raise his spirit and to practice his skill.