Between Sessa and Cintura | Entre Sesa et Cintura

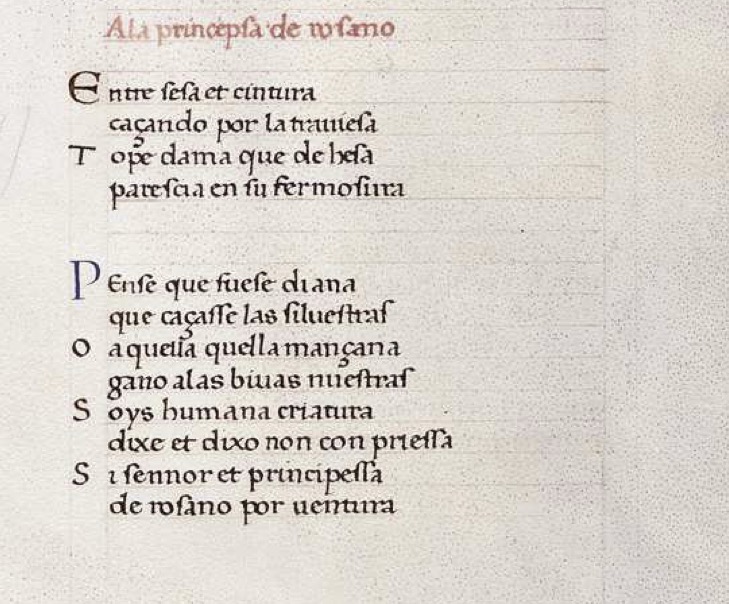

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España MS, VITR/17/7, f.136v [Public domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

This poem is a serranilla, an evolution of the Provençal pastorela. Written in short verse ( arte menor), serranillas narrate a courtly poet’s encounter with a mountain woman. This is one of six compositions in the genre by fifteenth-century author Carvajal (or Carvajales). Very little is known about Carvajal’s life. His poetry is linked to the Neapolitan court of Alfonso the Magnanimous in Naples (r. 1442-1458) and to that of Alfonso’s son Ferrante (r. 1459-1494). In addition to his famous serranillas, Carvajal is also known for his literary epistles and ballads.

In this poem, Carvajal subverts some of the genre’s conventions, as he does not meet a serrana but a lady of the court—the Princess of Rossano—in the context in which he would have normally run into a rustic woman. Upon encountering the lady, the poet ponders her beauty with references to biblical and mythological characters.

Introduction to the Source

The poem is copied in Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, VITR/17/7, fol. 136v-137r. This manuscript is a copy of the poetry collection known as the Cancionero de Estúñiga , ca. 1465. It has been digitized: http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000051837. It contains a compilation of mostly Castilian poems, including ballads, as well as a few Italian compositions. Their authors accompanied the King of Aragon, Alfonso the Magnanimous, in Naples in the mid-fifteenth century.

About this Edition

The text has been punctuated. Word separation and capitalization follow modern usage. Elisions have been marked with an apostrophe.

Further Reading

Carvajal. Poesie. Edited by Emma Scoles. Edizioni dell’Ateneo, 1967.

- Critical edition of Carvajal’s poetry.

Gerli, E. Michael. “Chapter 6. The Libro in the Cancioneros.” Reading, Performing, and Imagining the ‘Libro del Arcipreste’.

University of North Carolina Press, 2016, esp. pp. 194-203.

- Reassessment of Caravajal’s serranillas in view of their intertextual relationship with the Libro de buen amor.

Marino, Nancy F. La serranilla española: notas para su historia e interpretación. Scripta Humanistica, 1987.

- Study of the serranilla genre, with attention to Carvajal’s poems in chapter 5.

Between Sessa and Cintura | Entre Sesa et Cintura

Entre Sesa et Cintura

caçando por la trauiesa,

tope dama que dehesa

parescia en su fermosura.

5 Pense que fuese Diana

que caçasse las siluestras,

o aquella que lla1 mançana

gano a las biuas muestras.2

“Soys humana criatura?”

10 dixe, et dixo, non con priessa,

“Si sennor, et principessa

de Rosano por uentura”.

O, flor de toda bellesa,

o, templo de honestidat,

15 palacio de gentilesa,

fundamiento de bondat,

mi sententia uos condena;

que si en aquel templo de Baris

uos fallara l’ynfante Paris,

20 non fuera robada Elena.

Nin de Bersabe, Dauid

non se dexara vençer,

nin Usrias tornara en lid

por sus dias fenescer;

tanto soys de gracia llena

que si iuntas uos mirara,

muy menos se enamorara

Archiles de Poliçena.

Between Sessa and Cintura

While hunting across the countryside,

I came upon a lady who like a goddess

Looked; such was her beauty.

5 I thought she was Diana,

Hunting wild beasts,

Or her who the apple

Demonstrably won.

“Are you a human creature?”

10 I said, and she said with no hurry,

“Yes sir, and the Princess

Of Rossano by good fortune.”

Oh, flower of extreme beauty,

Oh, temple of honesty,

15 Palace of courtesy,

Foundation of goodness,

My sentence condemns you;

If you had been in that temple of Bari

And had met Prince Paris,

20 Helen would not have been stolen away.

Neither by Bathsheba, David

Would have been conquered,

Nor Uriah would have returned to the battle

To end his days;

25 For you are so full of grace

That had [Achilles] seen the two of you next to each other,

He would have never fallen in love

With Polyxena.

Critical Notes

-

The original manuscript states quella here.

-

This is a correction of nuestras (Scoles 1967: 118n8).