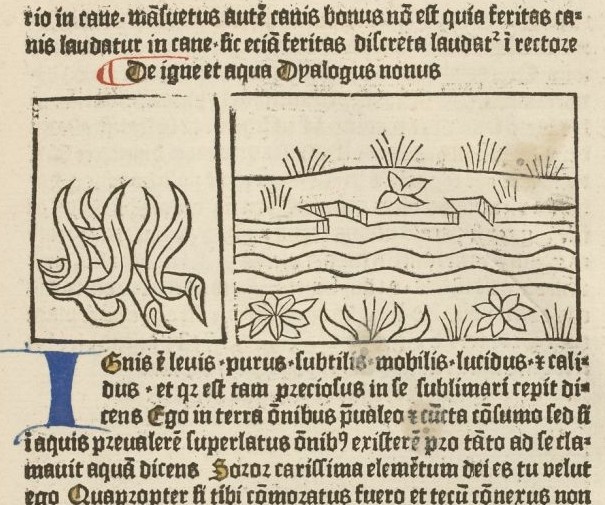

Concerning Fire and Water | De igne et aqua

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Arsenal, RESERVE FOL-BL-911, f.17r [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

The Dialogus Creaturarum (‘Dialogue of Creatures’), of which this text is one of eight published by the Global Medieval Sourcebook, was composed in the fourteenth century. Its authorship remains debated, though it was historically attributed to either Nicolaus Pergamenus, about whom little is known, or Magninus Mediolanensis (also known as Mayno de Mayneriis), who was a physician. In recent years, beginning with Pierre Ruelle in 1985, scholars have tended towards the conclusion that the Dialogus was compiled in Milan, though not necessarily by Magninus.

The text consists of 122 dialogues largely populated by anthropomorphic ‘creatures’, loosely defined; sections translated for the Global Medieval Sourcebook feature elements (fire, water), planetary bodies (the Sun, the Moon, Saturn, a cloud), animals (the leopard and unicorn), as well as a talking topaz. Each dialogue is further divided into two sections, the first part depicting an encounter between these creatures—two is the usual number, though some dialogues have one or three—that ends in a violent conflict. This experience is summed up in a moral, typically delivered by the defeated party, which is then exemplified in the second half of the dialogue through citations from historiography, literature, and sacred scripture. Common texts cited include the pagan authors Seneca the Younger and Valerius Maximus, along with the Christian writers Paul, Augustine, and John Chrysostom and compilations such as the Vitae patrum (‘Lives of the Fathers’) and Legenda aurea (‘Golden Legend’).

The great precision with which these references are cited—often including book and chapter numbers—suggests that the Dialogus was designed as a reference text containing recommendations for further reading, and more specifically as a handbook for ‘constructing sermons’ (as indicated in the Preface). This purpose does not, however, detract from its entertaining style, which derives in no small part from the passionate dialogue that takes place between the ‘creatures’ and the fast-paced descriptions of their battles against one another. These features explain the popularity of the Dialogus, which ran through numerous editions from the late fifteenth century onwards. The illustrated text compiled by Gerard Leeu was printed eight times in the eleven years from 1480 to 1491, once in French, twice in Dutch, and five times in Latin.

Introduction to the Source

Two manuscript versions of the Dialogus Creaturarum exist. Of these, only the so-called ‘short redaction’ has been printed. Gerard Leeu opted for this version of the text in the first Latin edition (1480), and all the vernacular translations are based upon it. The ‘short redaction’ is attested in twelve manuscripts from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and is thought to best reflect the original text, which was composed after 1326. This dating derives from the fact that it borrows heavily from a compilation, the Libellus qui intitulatur multifarium, which was compiled at Bologna in that year (see Ruelle 1985, p. 22). In contrast, the ‘long redaction’ survives in only two manuscripts, both of which are comparatively late (in or after 1431): Toledo, Biblioteca Capitular, 10-28 and Torino, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria, H. III. 6. In these manuscripts, the Dialogus Creaturarum is commonly presented under the title Contemptus Sublimitatis (‘The Contempt of Worldly Power’), which reflects its structure as a handbook of moral examples.

About this Edition

The source used for transcription and translation is Johann Georg Theodor Grässe’s 1880 edition, entitled Die beiden ältesten lateinischen Fabelbücher des Mittelalters: des Bischofs Cyrillus Speculum Sapientiae und des Nicolaus Pergamenus Dialogus Creaturarum (Tübingen: Literarischen Verein in Stuttgart). This edition can be accessed online here. Grässe bases his text on the 1480 edition by Gerard Leeu, which is itself most likely derived from several of the manuscript copies; for a full list, see Cardelle de Hartman and Pérez Rodríguez 2014, pp. 199-200. A late medieval printed version of the text, dating from 1481, is held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris and is available to view online here.

Further Reading

Cardelle de Hartman, Carmen, and Estrella Pérez Rodríguez. “Las auctoritates del Contemptus Sublimitatis (Dialogus Creaturarum).” Auctor et auctoritas in Latinis medii aevi litteris/Author and Authorship in Medieval Latin Literature: Proceedings of the VIth Congress of the International Medieval Latin Committee (Benevento-Naples, November 9-13, 2010), edited by Edoardo D’Angelo and Jan Ziolkowski, Florence: SISMEL - Edizioni di Galluzzo, 2014, pp. 199-212.

- Demonstrates that instead of nine manuscripts as previously thought, there exist fifteen complete manuscripts and a fragment, an outlines these manuscripts’ relationship to one another.

Kratzmann, Gregory C, and Elizabeth Gee, eds. The Dialoges of Creatures Moralysed: A Critical Edition. Leiden: Brill, 1988, pp. 1-64.

- Edition of the medieval English translation first published in 1530 (original author unknown), but the introduction contains information on the translation history and dissemination of the Latin Dialogus more generally.

Rajna, Pio. “Intorno al cosiddetto Dialogus creaturarum ed al suo autore.” Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 10, 1887, pp. 75-113.

- Advances arguments for two possible authors: Nicolaus Pergamenus and the Milanese doctor Mayno de Mayneriis, with a strong preference for the latter, and summarises the style and contents of the Dialogus.

Ruelle, Pierre, ed. Le “Dialogue des creatures”: Traduction par Colart Mansion (1482) du “Dialogus creaturarum’’ (XIVe siècle). (Classe des Lettres et des Sciences Morales et Politiques, Collections des Anciens Auteurs Belges, n.s. 8), Brussels: Palais des Académies, 1985, pp. 1-80.

- Annotated edition of the medieval French translation by Colart Mansion, but the introduction outlines the manuscript tradition and authorship of the Latin Dialogus.

Schmitt, Jean-Claude. “Recueils franciscains d’exempla et perfectionnement des techniques intellectuelles du XIIIe au XVe siècle.” Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 135, 1977, pp. 5-21.

- Discusses the front matter in early manuscripts of the Latin Dialogus, which contained both a list of titles and an alphabetical index of moral lessons to facilitate citation.

Concerning Fire and Water | De igne et aqua

De igne et aqua, dial. 9.

Ignis est lenis, purus, subtilis, mobilis, lucidus et calidus, et quia est tam pretiosus, in se sublimari cœpit dicens: ego in terra omnibns prævaleo et cuncta consumo, sed si in aquis prævalerem, superlatus omnibus existerem. Pro tanto ad se clamavit aquam dicens: soror carissima, elementum Dei es tu velut ego, quapropter, si tibi commoratus fuero et tecum connexus, non solum magnus sed magnificentior et excellentior apparebo. Unde obsecro te, permitte me tecum morari et in te gloriari.

Aqua vero simulare se ingeniose cœpit dicens: desiderio desideravi hoc pascha tecum manducare, accede ad me secure et te pro viribus meliorabo. Ignis quoque hoc audiens jucundari cœpit et amicabiliter ad aquam intravit, aqua vero, dum ignem in se haberet, assistentibus sibi dixit: iste inimicus et contrarius est generis mei; hic me sæpe consumpsit et ad nihilum redegit, modo me vindicare possum et ipsum exstinguere, si volo, sed juxta verbum apostoli nolo reddere malum pro malo, ne seculum privetur tanto bono, tamen volo ipsum aliquantulum humiliare. Et hæc dicens parum collegit se et in ignem mingere cœpit. Et ob hoc orare aquam ignis cœpit, ue ipsum exstiugueret. Aqua vero miserta est ei nec eum ex toto exstinxit, sed ad terram ipsum deduxit dicens: Deo daraus dulcera sonum reddendo pro malo bonum.

Sed multi hodie per contrarium reddunt pro malo malum, cum volunt vindictam assumere nolentes offensas dimittere. Propter quod Hieronimus dicit: quoniam Deus donavit in Christo peccata nostra, sie et uos dimittamus his, qui in nobis peccant, et Dei imitatio injuriam nobis faetam frangit et revocat. Sicut legitur in historiis Alexandri, quod, cum quidam eum graviter offendisset, nolebat ei dimittere, Aristoteles autem hoc cognoscens perrexit ad eum et ait: volo, domine, quod hodie sis victoriosus ultra quod fuisti. Quo respondente ait: bene volo. Cui ille: tu, rex, superasti omnia regna mundi, sed hodie tu superatus es, quia, si te permittis superari, victus es; si tu quoque vincis temetipsum, victoriosus eris, quia, qui semetipsum vincit, contra omnia fortis est, ut dicit philosophus. Ad hæc verba vindictam remisit Alexander et placatus est. Propter quod dicitur Prov. XVI: melius est patiens viro forti et qui dominatur animo suo expugntore urbium.

Concerning Fire and Water, the ninth dialogue

Fire is light, pure, fine, mobile, bright, and hot. He began to exalt himself because he was so valuable. “I prevail over all on earth; I eat up all on earth. If I were to prevail against Water, I would be revered beyond all things.” For this reason, he called Water to him and said, “Dearest sister, you are an element of God like me. If I were to stay with you and be joined to you I would seem not only great but even more magnificent and excellent. I beg you, let me stay with you and revel in you.”

Water began to pretend shrewdly and said, “I too wanted to feast with you this Easter. Do not worry1 ; come over to me and I will improve you to the best of my ability.” Hearing these words, Fire began to rejoice and entered Water in a friendly manner. Once Water held Fire in herself, she said to those around her, “This is my enemy and the opposite of my nature. He has often devoured me and turned me back to nothing. I could claim revenge and extinguish him if I wanted to. However, in accordance with the command of the Apostle, I refuse to exchange wrong for wrong, lest the world be robbed of such a great good. Nevertheless I wish to humiliate him a little.” Speaking thus, she collected herself somewhat and began to urinate onto Fire, who started to beg Water not to extinguish him. Indeed, Water took pity on him and did not extinguish him entirely, but led him back to dry land2, saying, “We offer up a sweet song to God by exchanging what’s bad for what is good3.”

On the contrary, however, many people today fight wrongs with wrongs. Indeed, they want to take vengeance and refuse to forget any offense. On this matter, Hieronimus says, “Just as God forgave our sins in Christ, so we must forgive those that sin against us; our imitation of God breaks and revokes any injury that we have suffered.” It is written in the histories of Alexander that when someone once offended him badly, he was not willing to forgive them. However, Aristotle took notice and went over to Alexander. “I want, lord, for you to be even more victorious today than you have ever been before.” “I desire this too,” said Alexander. In response, Aristotle said, “King, you have overcome all the kingdoms of the world, but today you have been overcome. After all, if you allow yourself to be overcome [by vindictiveness], then you are conquered. However, if you conquer yourself, you shall be all the more victorious, since whoever conquers himself is mighty against all. So sayeth the philosopher.” Hearing these words, Alexander forgave the offense and regained his calm. In the same vein, consider Proverbs XVI: “A patient man is better than a strong man, and he who is lord of his soul is better than a conqueror of cities.”

Critical Notes

-

A more literal translation could be ‘Come over securely to me’, but I have opted to translate ‘secure’ using the imperative ‘Do not worry.’

-

I have added the adjective ‘dry’ because of the English idiom ‘dry land’.

-

The Latin saying rhymes; while this cannot be fully replicated in English, I have tried to reflect this lyricism.