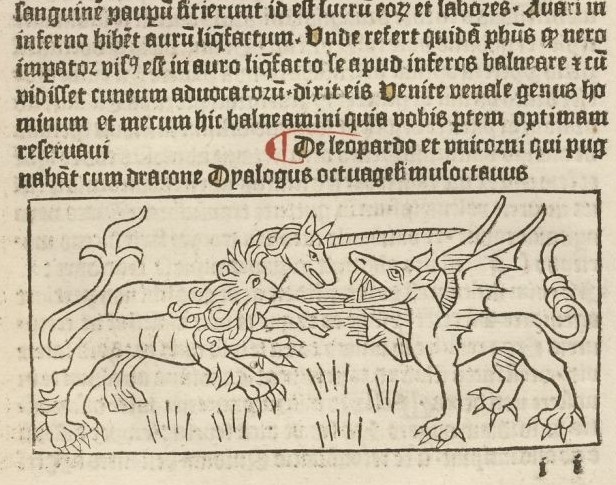

Concerning the Leopard and the Unicorn Who Fought the Dragon | De leopardo et unicorni

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Arsenal, RESERVE FOL-BL-911, f.73r [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

The Dialogus Creaturarum (‘Dialogue of Creatures’), of which this text is one of eight published by the Global Medieval Sourcebook, was composed in the fourteenth century. Its authorship remains debated, though it was historically attributed to either Nicolaus Pergamenus, about whom little is known, or Magninus Mediolanensis (also known as Mayno de Mayneriis), who was a physician. In recent years, beginning with Pierre Ruelle in 1985, scholars have tended towards the conclusion that the Dialogus was compiled in Milan, though not necessarily by Magninus.

The text consists of 122 dialogues largely populated by anthropomorphic ‘creatures’, loosely defined; sections translated for the Global Medieval Sourcebook feature elements (fire, water), planetary bodies (the Sun, the Moon, Saturn, a cloud), animals (the leopard and unicorn), as well as a talking topaz. Each dialogue is further divided into two sections, the first part depicting an encounter between these creatures—two is the usual number, though some dialogues have one or three—that ends in a violent conflict. This experience is summed up in a moral, typically delivered by the defeated party, which is then exemplified in the second half of the dialogue through citations from historiography, literature, and sacred scripture. Common texts cited include the pagan authors Seneca the Younger and Valerius Maximus, along with the Christian writers Paul, Augustine, and John Chrysostom and compilations such as the Vitae patrum (‘Lives of the Fathers’) and Legenda aurea (‘Golden Legend’).

The great precision with which these references are cited—often including book and chapter numbers—suggests that the Dialogus was designed as a reference text containing recommendations for further reading, and more specifically as a handbook for ‘constructing sermons’ (as indicated in the Preface). This purpose does not, however, detract from its entertaining style, which derives in no small part from the passionate dialogue that takes place between the ‘creatures’ and the fast-paced descriptions of their battles against one another. These features explain the popularity of the Dialogus, which ran through numerous editions from the late fifteenth century onwards. The illustrated text compiled by Gerard Leeu was printed eight times in the eleven years from 1480 to 1491, once in French, twice in Dutch, and five times in Latin.

Introduction to the Source

Two manuscript versions of the Dialogus Creaturarum exist. Of these, only the so-called ‘short redaction’ has been printed. Gerard Leeu opted for this version of the text in the first Latin edition (1480), and all the vernacular translations are based upon it. The ‘short redaction’ is attested in twelve manuscripts from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and is thought to best reflect the original text, which was composed after 1326. This dating derives from the fact that it borrows heavily from a compilation, the Libellus qui intitulatur multifarium, which was compiled at Bologna in that year (see Ruelle 1985, p. 22). In contrast, the ‘long redaction’ survives in only two manuscripts, both of which are comparatively late (in or after 1431): Toledo, Biblioteca Capitular, 10-28 and Torino, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria, H. III. 6. In these manuscripts, the Dialogus Creaturarum is commonly presented under the title Contemptus Sublimitatis (‘The Contempt of Worldly Power’), which reflects its structure as a handbook of moral examples.

About this Edition

The source used for transcription and translation is Johann Georg Theodor Grässe’s 1880 edition, entitled Die beiden ältesten lateinischen Fabelbücher des Mittelalters: des Bischofs Cyrillus Speculum Sapientiae und des Nicolaus Pergamenus Dialogus Creaturarum (Tübingen: Literarischen Verein in Stuttgart). This edition can be accessed online here. Grässe bases his text on the 1480 edition by Gerard Leeu, which is itself most likely derived from several of the manuscript copies; for a full list, see Cardelle de Hartman and Pérez Rodríguez 2014, pp. 199-200. A late medieval printed version of the text, dating from 1481, is held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris and is available to view online here.

Further Reading

Cardelle de Hartman, Carmen, and Estrella Pérez Rodríguez. “Las auctoritates del Contemptus Sublimitatis (Dialogus Creaturarum).” Auctor et auctoritas in Latinis medii aevi litteris/Author and Authorship in Medieval Latin Literature: Proceedings of the VIth Congress of the International Medieval Latin Committee (Benevento-Naples, November 9-13, 2010), edited by Edoardo D’Angelo and Jan Ziolkowski, Florence: SISMEL - Edizioni di Galluzzo, 2014, pp. 199-212.

- Demonstrates that instead of nine manuscripts as previously thought, there exist fifteen complete manuscripts and a fragment, and outlines these manuscripts’ relationship to one another.

Kratzmann, Gregory C, and Elizabeth Gee, eds. The Dialoges of Creatures Moralysed: A Critical Edition. Leiden: Brill, 1988, pp. 1-64.

- Edition of the medieval English translation first published in 1530 (original author unknown), but the introduction contains information on the translation history and dissemination of the Latin Dialogus more generally.

Rajna, Pio. “Intorno al cosiddetto Dialogus creaturarum ed al suo autore.” Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 10, 1887, pp. 75-113.

- Advances arguments for two possible authors: Nicolaus Pergamenus and the Milanese doctor Mayno de Mayneriis, with a strong preference for the latter, and summarises the style and contents of the Dialogus.

Ruelle, Pierre, ed. Le “Dialogue des creatures”: Traduction par Colart Mansion (1482) du “Dialogus creaturarum’’ (XIVe siècle). (Classe des Lettres et des Sciences Morales et Politiques, Collections des Anciens Auteurs Belges, n.s. 8), Brussels: Palais des Académies, 1985, pp. 1-80.

- Annotated edition of the medieval French translation by Colart Mansion, but the introduction outlines the manuscript tradition and authorship of the Latin Dialogus.

Schmitt, Jean-Claude. “Recueils franciscains d’exempla et perfectionnement des techniques intellectuelles du XIIIe au XVe siècle.” Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 135, 1977, pp. 5-21.

- Discusses the front matter in early manuscripts of the Latin Dialogus, which contained both a list of titles and an alphabetical index of moral lessons to facilitate citation.

Concerning the Leopard and the Unicorn Who Fought the Dragon | De leopardo et unicorni

Leopardus, ut Solmus dicit, animal est generatum ex leone et pardo. Horum feminæ sunt audaciores et fortiores maribus. Plinius: aliquis volens resistere leopardis furentibus, fricet allia inter manus, nee mora, leopardus resiliet nec resistet, quia odorem allii sustinere non potest. Leopardus subrufum colorem habet, maculas per totum nigras; multo minores sunt quam leones.

Leopardus, quando comedit aliquod venenum, stercus hominis quærit, quod comedit, et sanatur. Ambrosius. Hæ bestiæ sunt crudelissimæ naturaliter, ita quod sic domesticari non possunt, ut obliviscantur crudelitatis suæ. Domesticantur tamen ad venandum. Igitur dum ad prædam in venatione ducuntur, relaxantur, quam si quarto aut quinto saltu non potest capere, subsistit iratus fortiter, et nisi statim venator furenti bestiæ aliquam bestiam offerat, cujus sanguine placetur, irruit in venatorem vel quoscunque obvios, quia impossibile est placari eum nisi in sanguine.

Hic pugnabat cum dracone, sed non prævalebat, propter quod ad unicornem perrexit et humiliter ipsum obsecravit dicens: eminens es ac virtuosus et doctus belli, peto obnixe, quod me defendas a furore draconis. Unicornis autem se sublimare cœpit et audiens de se talia dici ait: verum dicis, quia doctus sum prælii, propterea optime defensabo te, noli pavere, cum enim aperiet draco os suum, in gutture ipsum cornu perforabo.

Cum autem ad draconem pariter venissent, leopardus bellum initiavit sperans de auxilio unicornis. Draco vero certavit adversus eos et ignem et fœtorem ex ore emittebat, sed cum os aperiret, unicornis quam citius cucurrit volens ipsum in gutture transvibrare, draco vero agitavit caput et unicornis cornu in terram fixit dicens moriendo: qui pro alio vult pugnare, cupit se trucidare. Sic enim stultum est, de se confidere ac de quo sibi non pertinet agonizare. Unde Eccl. XI: de ea re, quæ te non molestat, ne certaveris. Ergo require in animo tuo a te ipso, quis es, quid facere vis, utrum factum illud ad te pertineat. Ad minus ad alium te immiscere non debes.

Noli pro alio pugnare nec inter discordantes discordiam augere, sed fac, ut dicit Seneca: semper dissensio ab alio ineipiat, a te reconciliatio. Quidam bellantes aggressi sunt inimicum, sed alius quidam cucurrit volens ipsum defendere et armavit se versus inimicos illius. Illi autem dixerunt: amice, tibi injuriam non facimus, tolle quod tuum est et vade, quoniam de inimico nostro vindictam quærimus. Qui non acquiescens sermonibus corum ad bellum contra eos se paravit. Illi autem indignati cum inimico ipsum mutilaverunt.

Concerning the Leopard and the Unicorn Who Fought the Dragon

The leopard, as Solinus says, was born from the lion and the panther. The females of this species are braver and stronger than the males. Pliny writes that someone who wants to combat raging leopards should immediately rub garlic cloves between his hands. The leopard will retreat and fight no longer, since it cannot bear the odor of garlic. Moreover, leopards are orange in color but covered in black spots, and are are much smaller than lions.

Ambrose claims that if a leopard has eaten poison, it will seek out a man’s excrement, which, once consumed, heals it. These beasts are most cruel by nature, and cannot be tamed to forget their cruelty. Nevertheless they can be trained to hunt. When leopards are led to their prey in the course of a hunt, they become calm. However, if a leopard is unable to seize his prey in four or five leaps, he stops, profoundly angered. In such cases, unless a hunter offers some animal to the furious beast, so as to placate it with blood, it will charge at the hunter or whoever else happens to be in its way. It is impossible to calm a leopard down except by bloodshed 1.

Once, a Leopard fought with a Dragon, but he did not prevail. Therefore, he headed to the Unicorn and humbly entreated him, saying, “You are lofty, and virtuous, and learned in war. I beseech you with all my heart to defend me from the Dragon’s madness.” The Unicorn began to rise upon hearing such words spoken about himself. He said, “You speak truly, since I am battlewise, and I shall protect you in the best way possible. Do not fear, for when the Dragon opens his mouth I will pierce his throat with my horn.”

After they had found the Dragon together, the Leopard began the fight, pinning his hopes on the Unicorn’s help. The Dragon fought against them, spitting out fire and fumes. When he opened his mouth, the Unicorn charged at him as swiftly as he could, aiming to pierce through his throat. However, the Dragon shook his head, and drove the Unicorn’s horn into the earth. As the Unicorn died, the Dragon said to him, “He who wants to fight for another desires to slay himself. It is foolish to be so self-assured and to fight over that which does not concern you.” Indeed, as Ecclesiastes XI says, “Do not fight on account of that which does not vex you.” Make yourself certain as to who you are, what you desire to do, and whether the matter concerns you. At the very least, you should not implicate yourself with another. Do not fight for someone else, and do not add fire to fire2.

Do not fight for someone else, and do not add fuel to the fire.² Instead, follow the advice of Seneca: “Let conflict always begin from another, but let reconciliation always begin from you.” Once, some warriors attacked their enemy, but some other man hastened to the fight, wanting only to defend the enemy; he even took up arms against the warriors. Nevertheless, the warriors said, “Friend, we shall do you no injury. Take what is yours and depart, for we seek vengeance from our enemy alone.” The man, refusing to take heed of their words, prepared himself for war against them. Indignant, the warriors cut him down along with their enemy.

Critical Notes

Translation

-

A more literal translation would be “except in blood.“

-

A more literal translation would be “Do not grow discord among those who are already in conflict.”