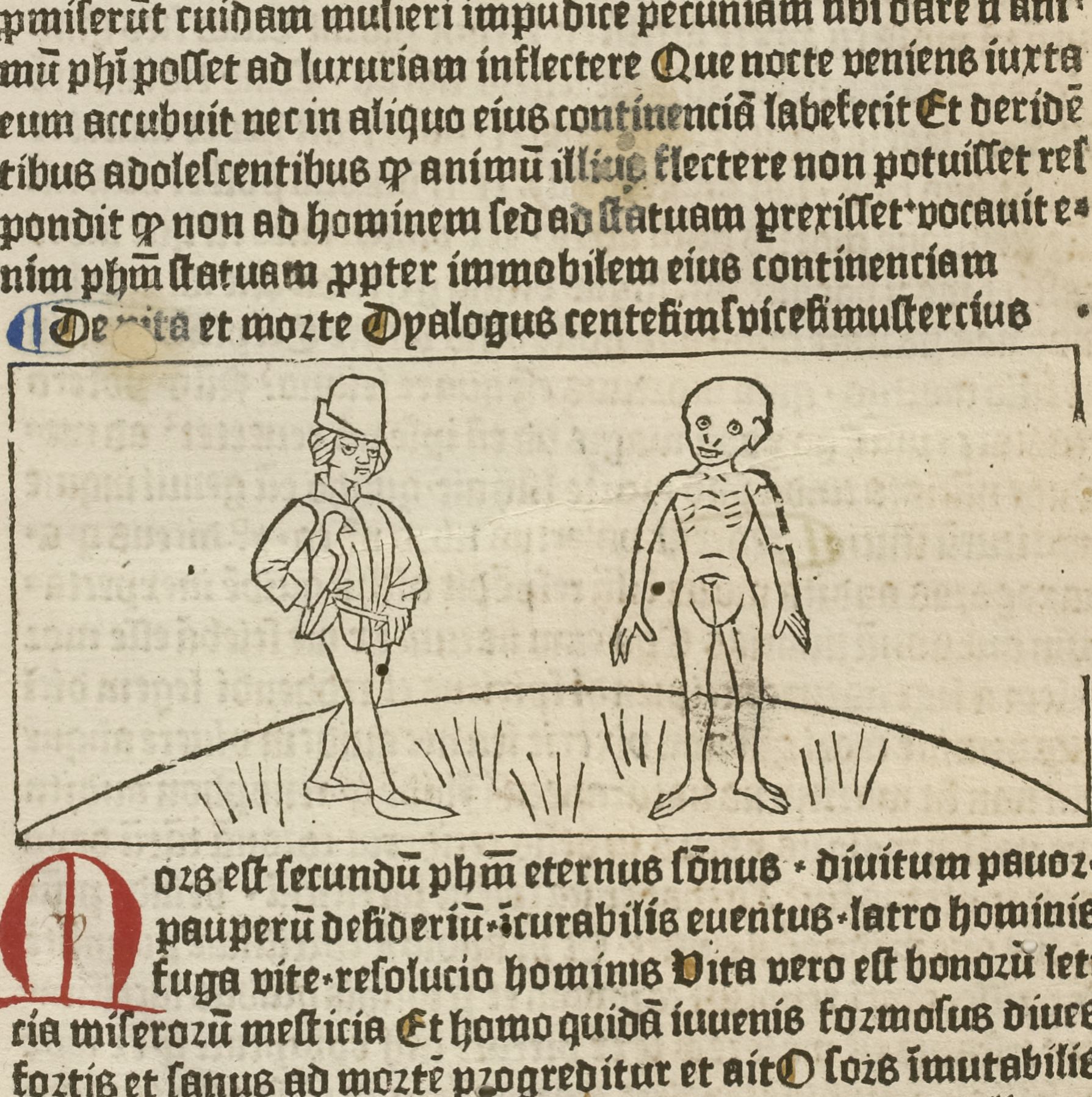

Concerning Life and Death | De vita et morte

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Arsenal, RESERVE FOL-BL-911, f.100r [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

The Dialogus Creaturarum (‘Dialogue of Creatures’), of which this text is one of eight published by the Global Medieval Sourcebook, was composed in the fourteenth century. Its authorship remains debated, though it was historically attributed to either Nicolaus Pergamenus, about whom little is known, or Magninus Mediolanensis (also known as Mayno de Mayneriis), who was a physician. In recent years, beginning with Pierre Ruelle in 1985, scholars have tended towards the conclusion that the Dialogus was compiled in Milan, though not necessarily by Magninus.

The text consists of 122 dialogues largely populated by anthropomorphic ‘creatures’, loosely defined; sections translated for the Global Medieval Sourcebook feature elements (fire, water), planetary bodies (the Sun, the Moon, Saturn, a cloud), animals (the leopard and unicorn), as well as a talking topaz. Each dialogue is further divided into two sections, the first part depicting an encounter between these creatures—two is the usual number, though some dialogues have one or three—that ends in a violent conflict. This experience is summed up in a moral, typically delivered by the defeated party, which is then exemplified in the second half of the dialogue through citations from historiography, literature, and sacred scripture. Common texts cited include the pagan authors Seneca the Younger and Valerius Maximus, along with the Christian writers Paul, Augustine, and John Chrysostom and compilations such as the Vitae patrum (‘Lives of the Fathers’) and Legenda aurea (‘Golden Legend’).

The great precision with which these references are cited—often including book and chapter numbers—suggests that the Dialogus was designed as a reference text containing recommendations for further reading, and more specifically as a handbook for ‘constructing sermons’ (as indicated in the Preface). This purpose does not, however, detract from its entertaining style, which derives in no small part from the passionate dialogue that takes place between the ‘creatures’ and the fast-paced descriptions of their battles against one another. These features explain the popularity of the Dialogus, which ran through numerous editions from the late fifteenth century onwards. The illustrated text compiled by Gerard Leeu was printed eight times in the eleven years from 1480 to 1491, once in French, twice in Dutch, and five times in Latin.

Introduction to the Source

Two manuscript versions of the Dialogus Creaturarum exist. Of these, only the so-called ‘short redaction’ has been printed. Gerard Leeu opted for this version of the text in the first Latin edition (1480), and all the vernacular translations are based upon it. The ‘short redaction’ is attested in twelve manuscripts from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and is thought to best reflect the original text, which was composed after 1326. This dating derives from the fact that it borrows heavily from a compilation, the Libellus qui intitulatur multifarium, which was compiled at Bologna in that year (see Ruelle 1985, p. 22). In contrast, the ‘long redaction’ survives in only two manuscripts, both of which are comparatively late (in or after 1431): Toledo, Biblioteca Capitular, 10-28 and Torino, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria, H. III. 6. In these manuscripts, the Dialogus Creaturarum is commonly presented under the title Contemptus Sublimitatis (‘The Contempt of Worldly Power’), which reflects its structure as a handbook of moral examples.

About this Edition

The source used for transcription and translation is Johann Georg Theodor Grässe’s 1880 edition, entitled Die beiden ältesten lateinischen Fabelbücher des Mittelalters: des Bischofs Cyrillus Speculum Sapientiae und des Nicolaus Pergamenus Dialogus Creaturarum (Tübingen: Literarischen Verein in Stuttgart). This edition can be accessed online here. Grässe bases his text on the 1480 edition by Gerard Leeu, which is itself most likely derived from several of the manuscript copies; for a full list, see Cardelle de Hartman and Pérez Rodríguez 2014, pp. 199-200. A late medieval printed version of the text, dating from 1481, is held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris and is available to view online here.

Further Reading

Cardelle de Hartman, Carmen, and Estrella Pérez Rodríguez. “Las auctoritates del Contemptus Sublimitatis (Dialogus Creaturarum).” Auctor et auctoritas in Latinis medii aevi litteris/Author and Authorship in Medieval Latin Literature: Proceedings of the VIth Congress of the International Medieval Latin Committee (Benevento-Naples, November 9-13, 2010), edited by Edoardo D’Angelo and Jan Ziolkowski, Florence: SISMEL - Edizioni di Galluzzo, 2014, pp. 199-212.

- Demonstrates that instead of nine manuscripts as previously thought, there exist fifteen complete manuscripts and a fragment, and outlines these manuscripts’ relationship to one another.

Kratzmann, Gregory C, and Elizabeth Gee, eds. The Dialoges of Creatures Moralysed: A Critical Edition. Leiden: Brill, 1988, pp. 1-64.

- Edition of the medieval English translation first published in 1530 (original author unknown), but the introduction contains information on the translation history and dissemination of the Latin Dialogus more generally.

Rajna, Pio. “Intorno al cosiddetto Dialogus creaturarum ed al suo autore.” Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 10, 1887, pp. 75-113.

- Advances arguments for two possible authors: Nicolaus Pergamenus and the Milanese doctor Mayno de Mayneriis, with a strong preference for the latter, and summarises the style and contents of the Dialogus.

Ruelle, Pierre, ed. Le “Dialogue des creatures”: Traduction par Colart Mansion (1482) du “Dialogus creaturarum’’ (XIVe siècle). (Classe des Lettres et des Sciences Morales et Politiques, Collections des Anciens Auteurs Belges, n.s. 8), Brussels: Palais des Académies, 1985, pp. 1-80.

- Annotated edition of the medieval French translation by Colart Mansion, but the introduction outlines the manuscript tradition and authorship of the Latin Dialogus.

Schmitt, Jean-Claude. “Recueils franciscains d’exempla et perfectionnement des techniques intellectuelles du XIIIe au XVe siècle.” Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 135, 1977, pp. 5-21.

- Discusses the front matter in early manuscripts of the Latin Dialogus, which contained both a list of titles and an alphabetical index of moral lessons to facilitate citation.

Concerning Life and Death | De vita et morte

Mors secundum philosophum et æternus somnus, divitum pavor, pauperum desiderium, incurabilis eventus, latro hominis, fuga vitæ, resolutio hominis. Vita vero est bonorum lætitia, miserorum mœstitia. Et homo quidam juvenis formosus, dives, fortis et sanus ad mortem progreditur et ait: o sors immutabilis, miserere mei et exaudi me, supplicium, quod a te exspecto, noli emittere ad me, aurum et argentum, lapides pretiosos, mancipia, equos, fundos, prædia, palatia, possessiones et quidquid vis, tibi dabo, tantumnodo noli me tangere. Cui mors : impossibilia petis, o frater, non sunt petenda a Deo nisi honesta et possibilia ideoque non sapienter locutus es, quia dicitur homini, mors ubique te exspectat et tu, si sapiens fueris, ubique eam exspectabis. Dicitur enim Psalm. LXXXVIII: quis est homo, qui vivit et non videbit mortem?

Quasi dicat, nullus. Unde versus: per nullam sortem poteris evadere mortem. Mors resecat, mors omne necat, quod carne creatur. Ergo patienter recipe me, quia tibi nihil novi veni facere. Ait enim Seneca: nemo tam imperitus est, ut nesciat se aliquando moriturum. Tamen, mors cum propere accesserit, tremis, ploras. Quid fles, quid ploras, quia morieris, ad hanc legem natus? Quid tibi novi est? Ad hanc legem natus es, hoc patri tuo accidit, hoc et matri et majoribus tuis, hoc omnibus ante te, hoc omnibus post te, vita enim cum exceptione mortis data non est.

Lex universalis est, quæ jubet nasci et mori, hoc autem intelligas vitam gerendo. Ait idem: debemus nos portare, quod non possumus vitare. Exemplum de David de filio mortuo: quia mortuus est, quare jejuno? Numquid potero revocare eum? Ego vadam magis ad eum, ipse non revertetur ad me. Unde nuntiata cuidam philosopho morte filii ait: quoniam eum genui, inquit, moriturum scivi. Narrat Valerius 1. V. c. X dicens, quod Anaxagoras audita morte filii respondit : nihil quidem inexspectatum aut novum nuntias, ego eum natum ex me sciebam esse mortalem, atque a lege naturae accipiendi spiritus et reddendi legem didici, neminem mori, qui non vixerit, ita nec quidem vivere aliquem, qui non sit moriturus naturaliter.

Ibidem, quod Xenophon audita morte filii sui majoris natu, qui in bello occiderat, coronam tamen deponere contentus fuit. Agebat enim solemne sacrificium, deinde percontatus, quomodo occubuisset, ut audivit fortissime pugnantem interiisse, capiti reposuit coronam et per numina, quibus sacrificabat, testatus est, majorem se ex virtute filii voluptatem quam ex morte amaritudinem sentire. Narrat Hieronimus, quod sancta quædam et nobilissima mulier, cum corpusculum mariti sui defuncti, quem amabat et quem plorabat, adhuc non esset humatum, in ipso sepulturæ ejus die duos simul perdidit filios. Rem sum dictutrus incredibilem, sed Christo teste non falsam.

Quis illam non putaret passis crinibus, veste conscissa lacerantem pectus incedere? Lacrynmæ quidem gutta non fluxit, stetit immobilis et advoluta ad pedes Christi, quasi ipsum teneret, ait: expedita, inquit, servitura sum, domine, tibi, quia me a tanto onere liberasti. Legitur in Chronicis imperatorum, quod uxor Octaviani tumulavit quendam filium suum nomine Drusum, et licet esset pagana, tamen per magnum sensum naturalem exsistentem. in se, deposuit omnia signa moeroris dicens: quid prodest timere, quod non potest evitari, et flere, quod, dum venerit, non potest revocari?

Unde Seneca : non affligitur sapiens filiorum amissione nec amicorum, eodem modo ferre potest illorum mortem, quo suam exspectat. Et quidem memoria mortis est quoddam frenum refrenans hominem, ne nimis effluat et discurrat per latitudines cupiditatum et libidinum. Mortis meditatio summa est philosophia, ut dicit Plato. Unde dicitur in Vita Johannis elemosinarii, quod antiquitus, postquam imperator coronatus erat, statim ingrediebantur ad eum aedificatores monumentorum dicentes eidem: de quo vel de quali metallo jubes, imperator, fieri monumentum tuum ?

Insinuantes hoc ei, ut sciret, quod homo corruptibilis et transitorius esset, ut curam baberet animæ suæ et regnum pie disponeret et gubernaret, juxta illud Eccl. VII : memorare novissima tua et in aeternum non peccabis? Recitat Alfonsus in tractatu suo de prudentia, quod mortuo Alexandro, cum fieret ei sepulchrum aureum, convenerunt ad eum plurimi philosophi, ex quibus unus dixit: Alexander ex auro fecit thesaurum, nunc e contrario aurum de eo fevit thesaurum.

Alius quoque dixit: Alexander heri populis imperabat, hodie populi imperant illi. Alius vero dixit: heri Alexander multos potuisset a morte liberare, hodie ipsius mortis jacula in se missa non potuit evitare. Alius dixit: Alexander heri ducebat exercitum, hodie ab illis ducitur ad sepulturam. Alius dixit: Alexander heri terram premebat et hodie ab ea premitur ipse. Alius dixit: heri Alexandrum gentes timebant, hodie eum vilem reputant. Alius dixit: Alexander heri amicos habuit, hodie æquales omnes habet. Alius dixit: ei heri non sufficiebat totus mundus, hodie sepultura quinque pedum est contentus.

Si quis ista consideraret, dictis, modis se refrenaret. Dicitur de vivente homine, quod quasi sterquinilium in fine perdetur, Job. XX. Ideo praecipitur Eccles. XXVI : memento finis, melius est ad domum luctus ire quam ad domuru convivii; ibi enim finis eunetorum admonetur hominum et vivens cogitat, quid futurum sit ei, quia scilicet simili fine claudendus sit. Eccl. VII : idcirco attendite et considerate, quod in morte cujuscunque nasus frigescit, dentes nigrescunt, facies pallescit, venae et nervi corporis rumpuntur, cor, ut dicitur, prae nimio calore dividitur, omnia membra tamquam ligna et lapides arescunt.

Nihil in mundo tam abhominabile et taediosum sicut cadaver mortui ; in aquis non projicitur, ne aquae inficiantur, in aere non suspenditur, ne aer corrumpatur, sed sicut venenum pessimum in foveam projicitur et, ne amplius videatur, terra super ipsum velociter tumulatur. Ecce gloria mundi qualiter clauditur! Clauditur in fovea fœtidissima, ubi ejus cor marcescit, emarcescunt oculi in sua fortitudine, aures cadunt de capite, nasus exstirpatur de facie, lingua putrescit in ore, cor ejus crepat in corpore.

Sed heu, heu mihi, domine, quid oculi delectabuntur videre pulchra, aures audire vana, nasus odorare suavia, lingua loqui turpia et inutilia, os degustare dulcia, cor cogitare vana et vilia. Unde Bernardus: quid superbis, pulvis et cinis, cujus conceptus culpa, nasci miseria, vivere pœna et mori angustia? Praecipue enim, cum miser homo ad mortem vel ad senectutem declinat, cor ejus concutitur, caput affligitur, langnet spiritus, fœtet anhelitus, facies rugatur, statura curvatur, caligant oculi, vacillant articuli, nares defluunt, crines deficiunt, dentes putrescunt, vires amittit, modo lætus modo tristis modo infirmus efficitur.

O conditio misera, quare non advertis, quam miserabilis sit hæc vita? Considera ergo genitores et paternos et antecessores, cum non eos invenies, et ut Bernardus inquit : dic mihi, ubi sunt amatores mundi, qui ante pauca tempora nobiscum erant? nihil ex iis remansit nisi cineres, et ideo dic mihi, quaeso, ubi sunt barones, ubi principes, ubi primates? certe quasi umbra pertransierunt et in nihilum redacti sunt.

Item Augustinus: vade ad sepulchrum, accipe ossa et discerne, si potes, quis dominus, quis servus, quis pulcher, quis deformis, quis nobilis, quis ignobilis, quis sapiens, quis ideota, et de hoc non poteris recognoscere. Unde cogita, unde veneris, et erubesce, ubi es, et ingemisce, quo vadis, et pertimesce, ut superius revenire valeas, unde expulsus es. Quod nobis praestare dignetur ille, qui sine fine vivit et regnat per omnia secula seculorum. Amen.

Concerning Life and Death

Death, according to the Philosopher, is eternal sleep, the fear of the wealthy, the desire of the poor, an irremediable outcome, the bandit of mankind, the rout of life, and Man’s release. Life, on the contrary, is the delight of the good and the grief of the evil. Some young man, handsome, wealthy, strong, and healthy, approaches death and says: ‘O unchangeable Destiny, have pity upon me and hear my entreaty: that you not visit upon me the punishment which I expect from you. I shall give you gold and silver, precious stones, slaves,1 horses, estates, manors, palaces, property, and whatever you want, as long as you do not lay hands upon me.’ Death says to him: ‘O brother, you ask for that which is impossible, and you should not ask anything from God unless that which is honorable and possible. Hence, you have not spoken wisely, and indeed it is said to Man, “Death awaits you everywhere and if you are wise, you shall expect Her everywhere too.” After all, Psalm 882 says “What man can live and not see death?” as if to mean that there is no such man.

‘Hence the verse: “You shall not be able to avoid death through any act of Fate.”3 Death cuts off and kills everything which is created in flesh; accept me with equanimity, since I have not come to do anything out of the ordinary to you.’4 After all, Seneca writes: ‘No one is so ignorant that he does nevertheless, when death draws near, you tremble and cry. What do you find odd in this? You were born under this law; this fate befell your father, as well as your mother and your ancestors, along with all who came before and will come after you, for life is never granted together with immunity to death.

It is a universal law which dictates that we be born and then die, and you should understand this in the course of living your life.’5 He also writes: ‘We must bear that which we cannot avoid.’6 David, upon the death of his son, exemplified this maxim: ‘Since he is dead, why do I fast? Surely I shan’t be able to summon him back? On the contrary, I shall go to him, but he will not come back to me.’7 Hence some philosopher also responded thus, after the death of his son had been reported to him: ‘Given that I fathered him’, he said, ‘I knew that he must die.’8 Valerius [Maximus] also tells this story at Book 5 Chapter 10 [of his Memorable Doings and Sayings ], by noting that Anaxagoras, upon hearing of the death of his son, responded: ‘You announce to me nothing unexpected or new.9 I knew that he was born from me and mortal.10 I also learned that the terms upon which we receive breath and give it back are derived from the law of Nature, so that no one dies who has not lived, and likewise no one lives who will not die in accordance with his nature.’

In the same place, Valerius reports that Xenophon, having heard of the death of his elder son, who had fallen in battle, was content merely to take off his garland. For instance, he was conducting a regular sacrifice, when he then asked how his son had died, and learned that he had perished while fighting most courageously, he replaced the garland upon his head and called the gods to whom he was sacrificing to witness that he felt more pleasure from his son’s bravery than bitterness from his death.11 Jerome relates that a certain holy woman, of the utmost nobility, while the body of her deceased husband—whom she had loved and lamented— was yet unburied, lost her two sons on the very day that the burial was to take place. I am going to tell an unbelievable thing, but one which is not false, as Christ is my witness.

Who would not think that she would have loosened her hair, torn her clothes, and scratched her breast? Yet not even one tear fell from her eyes. She stood motionless and prostrated herself at the feet of Christ, as though she held Him in her hands, and said: ‘I shall serve you readily in future, Lord, because you have freed me from such a great burden.’12 One reads in the chronicles of the emperors that Octavian’s wife buried one of her sons by the name of Drusus, and even though she was a pagan, she nevertheless shed all signs of her grief through the help of some great and natural feeling which existed within her, saying, ‘What is the use of fearing that which cannot be avoided, and of weeping over that which cannot be called off once it has arrived?’13

Hence Seneca: ‘The wise man is distressed neither by the loss of his sons nor that of his friends; he can endure their deaths in the same way as he expects his own.’14 And indeed the memory of death is a type of harness which reins in Man, lest he should conduct himself too freely and run wild through the latitudes of his desires and lusts. As Plato says, ‘Practicing how to die is the highest form of philosophy.’15 Hence it is said in the Life of John the Almsgiver that in ancient times, after an emperor was crowned, builders of monuments would immediately go up to him and say: ‘From what or what sort of metal, Emperor, do you command your monument to be made?’16

They made this suggestion to him so he would know that Man is destructible and fleeting, and would take thought for his soul by organizing as well as governing his kingdom with piety, according to that saying from Ecclesiastes 7: ‘Be mindful of your final end, and you shall never sin.17 [St.] Alphonsus relates in his essay on wisdom that when Alexander died and a golden tomb was constructed for him, many philosophers gathered before it. One of them said, ‘Alexander made a treasure out of gold, but now on the contrary it is gold which has made a treasure out of him.’

Moreover, another said: ‘Yesterday Alexander was leading his people, but today he is being led by the people.’ Another, however, said: ‘Yesterday Alexander would have liberated many from death, today he cannot avoid sending the spike of his own death into himself.’ Another said: ‘Yesterday Alexander was leading his army, but today he is being led by them to his burial.’ Another said: ‘Yesterday Alexander weighed down the earth, but today he himself is being weighed down by it.’ Another said: ‘Yesterday the peoples feared Alexander, but today they hold him in contempt.’ Another said: ‘Yesterday Alexander had friends, but today he considers all men his equals.’ Another said: ‘Yesterday the entire world did not suffice for him, but today he is content with a grave spanning five feet.’

If anyone should consider these words, let him restrain himself within the allotted bounds. It is said of a living man that ‘he will perish forever like his own dung’, Job 20.18 Hence Ecclesiastes 26 commands: ‘Remember the end, it is better to visit the house of mourning than the house of partying, for there one is reminded of the end which befalls all men and, while alive, takes thought of what will happen to him, since he will certainly be confined by a similar end.’19 Ecclesiastes 7: Pay attention, therefore, and consider the fact that in death, everyone’s nose grows cold, their teeth grow black, their faces grow pale, the veins and nerves of their bodies break, and the heart, as they say, splits on account of excessive heat, and all the limbs dry out like timbers and stones.20

Nothing is more abominable and disgusting in the world than the corpse of a dead man: it is not thrown into the water lest it should contaminate the water, it is not hung in the air lest it should corrupt the air, but like the most foul poison it is thrown into a pit and earth is swiftly piled upon it in burial so that it is visible no longer. Look how the glory of the world is confined! It is confined in the most stinking pit, where its heart withers. The eyes, too, wither in their strength, and the ears fall from the head. The nose is uprooted from the face, the tongue rots in the mouth, and the heart rattles in the body.

But alas, alas for me, Lord: why will my eyes be pleased to see that which is beautiful, my ears to hear vanities, my nose to smell delicious things, my tongue to speak foul and useless words, my mouth to taste sweet foods, and my heart to ponder what is vain and inconsequential? Hence Bernard: ‘Why are you proud, dust and ash, having been conceived in sin and born in misery, to live in punishment and die in difficulty?’21 After all, especially when a wretched man declines into death or old age, his heart is shaken and his head afflicted; his spirit languishes, breath stinks, face is wrinkled, spine curves, eyes grow foggy, joints waver, nostrils droop, hair disappears, teeth rot, and he loses his strength. He is first made happy, then sad, and then weak.

O wretched condition, why do you not notice how miserable this life is? Consider therefore your parents and forefathers and ancestors, when you do not find them, and as Bernard said: ‘Tell me, where are the lovers of this world who were with us but a short time before? Nothing has remained of them except ashes, and therefore tell me, I beseech you, where are the barons, princes, and powerful men? Certainly they have fled on by like a shadow and been reduced to nothing.’22

Likewise Augustine: ‘Go to the cemetery, take up the bones and discern, if you can, who was a master, who a servant, who handsome, who noble and who not noble, who wise, who an imbecile’,23 and you will not be able to infer about this. Hence consider from where you have come, blush to think of where you are now, weep over where you are going, and be afraid as to whether you will be good enough to return up high, whence you have been expelled. Let Him, who lives forever and reigns over a world without end, deign to grant us this. Amen.

Critical Notes

Translation

-

Mancipia often refers to property more generally; however, as possessiones are mentioned within this sentence, it is likely that the author refers to “slaves”, who along with “horses” – the next item listed – would reasonably have populated the promised “estates, manors, palaces”, etc.

-

Psalm 88:49.

-

A popular memento mori verse, inscribed below a painting in the 14th-century Benedictine monastery of Sacro Speco in Subiaco.

-

There is no indication as to when Death’s speech ends, but this point is a logical break, and the narrtor certainly takes over by the end of this dialogue, for Death would ostensibly not end his speech with an “Amen”.

-

These ideas are a loose paraphrase of Sen. Ep. 76.11-13.

-

An approximation of Sen. Vit. Beat. 15.7: Ad hoc sacramentum adacti sumus, ferre mortalia nec per turbari iis, quae vitare non est nostrae potestatis (‘This is the sacred obligation by which we are bound – to submit to the human lot, and not to be disquieted by those things which we have no power to avoid’).

-

2 Samuel 12:23.

-

This line was spoken by no ‘philosopher’; it was originally spoken by Telamon, father of Ajax, in Ennius’ tragedy Telamo, line 319: ‘ego cum genui tum morituros scivi et ei rei sustuli’ (‘When I fathered children, I knew that they must die, and I brought them up for this purpose’). The misattribution may have arisen from the transmission of these verses in Cic. Tusc. Disp. 3.13.28, or, more likely, in Sen. De Cons. 11.

-

Novum also means ‘odd, strange’ in this context (cf. Hor. Carm. 1.2.6, nova monstra, ‘bizarre portents’).

-

These first two clauses ( nihil quidem…mortalem, corresponding to ‘You announce…and mortal’ in the translation) are taken almost word-for-word from Anaxagoras’ speech at Val. Max. 5.10 ext.3, but the following sentences in Anaxagoras’ purported response have been cobbled together from Valerius’ own comments, as set out a few lines below in the aforementioned chapter.

-

A summary, or rather a restructuring with large parts of the original Latin kept intact, of Val. Max. 5.10 ext.2.

-

Paraphrased very closely from Hier. Ep. 39.4. Significantly, the first-person aside (‘I am going to tell… as Christ is my witness’) is not an address to the reader on the part of the Dialogus ’ author, but lifted near-directly (with teste Christo in the original instead of Christo teste) from Jerome’s narration.

-

Source untraceable; most likely from one of the hundreds of versions of Martin of Opava’s Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum (‘Chronicle of the Popes and Emperors’).

-

Sen. Ep. 74.30, slightly simplified; the original liberorum (‘children’) has been changed to filiorum

(‘sons’), and eodem animo (‘in the same spirit’) to eodem modo (‘in the same way’).

-

The term meditatio mortis is distinctively Senecan (Sen. Ep. 54.2) but often associated with Plato’s Phaedo, where Socrates repeatedly associates this phrase (μελέτη θανάτου) with philosophy.

-

Paraphrased from the life of John ( De sancto Iohanne Elemosinario), chapter 27 of the Golden Legend.

-

Ecclesiastes 7:40.

-

Job 20:7.

-

None of the following text is from Ecclesiastes 26. Memento finis (‘Remember the end’) is from Sirach 36:10, and melius est…sit ei (‘It is better to…will happen to him’) is from Ecclesiastes 7:3. The last phrase, quia…claudendus sit (‘Since he will…similar end’) is an addition by the Dialogus ’ author.

-

This text is not from Ecclesiastes 7, but adapted from one of Odo of Cheriton’s Sermones Dominicales (‘Dominican Sermons’), specifically that on fol. 251 of British Library Egerton MS 2890, beginning: Considera quod in morte cuiuscumque nasus frigescit …

-

[Ps.-]Bernard of Clairvaux, Meditationes de humana conditione, PL 184, 0490B.

-

[Ps.-]Bernard of Clairvaux, Meditationes de humana conditione, PL 184, 0491.

-

Adapted from Augustine, Ad fratres in eremo commorantes 48, PL 40, 1329.