The Legend of the Damsel Carcayçiona | ءَالْرَاكُنْتَمِيانْتُ دَا لَذُنْزَالّ كركيسينُ

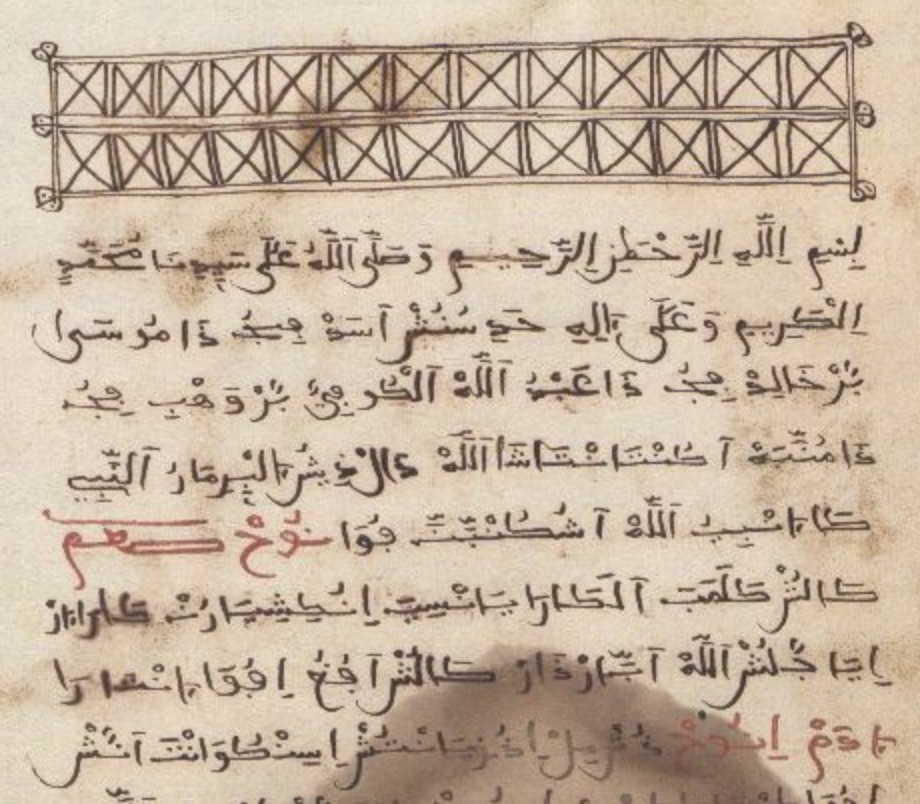

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, MS Junta 57, f.1v [Public Domain]

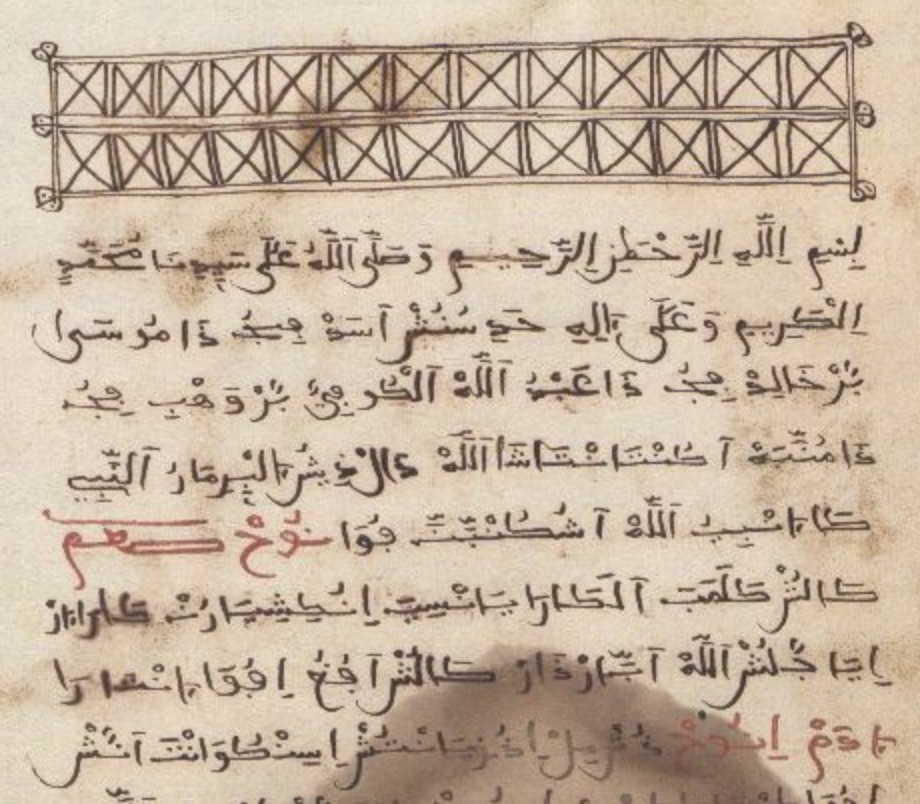

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, MS Junta 57, f.1v [Public Domain]