The Spring – The Hecatomb for Diane, VI | Le Printemps – L’hécatombe à Diane, VI

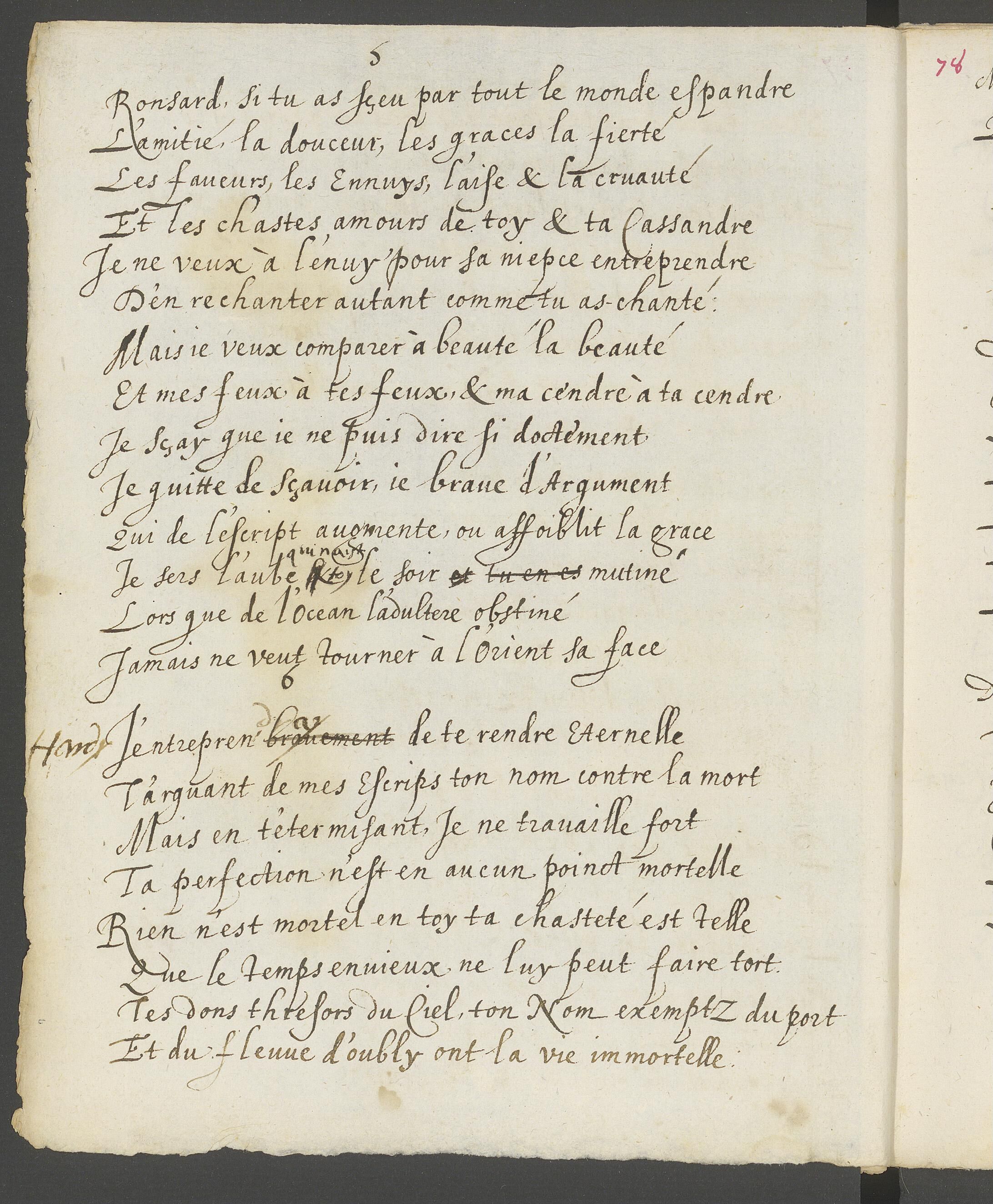

Bibliothèque de Genève, Detail from Le Printemps et divers textes, Bibliothèque de Genève, Archives Tronchin 157

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

Best known for his civil war epic Les Tragiques, Théodore Agrippa d’Aubigné (1552–1630) spent his early years in the thrall of Diane Salviati. Salviati was the niece of Cassandra, the muse of the famous French poet Ronsard. D’Aubigné’s work Le Printemps – ‘Spring’ – is composed of two parts. The first is a compilation of one hundred sonnets dedicated to his beloved, entitled L’hécatombe à Diane. The word ‘hecatomb’ evokes a sacrificial practice in Ancient Greece, where one hundred cattle or other livestock would be slaughtered in honour of the gods. Though the goal of d’Aubigné’s sonnets is ostensibly to praise Diane, his imagery is characteristically visceral, flavoured by his experience of the violence of France’s Wars of Religion (1562–1598). Diane’s family sheltered d’Aubigné following the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, but, as she was Catholic and d’Aubigné Protestant, their love was not to be. The author’s later works express some wistful reflections on the youthful exuberance that led him to idolize this unattainable woman. It is thought that L’hécatombe à Diane and the latter section of Le Printemps, the Stances et Odes, were composed in the early 1570s.

Introduction to the Source

This poem is a unicum copied in Zaragoza, Biblioteca de la Universidad de Zaragoza, MS 210, fol. 98v-99r (the Cançoner de Saragossa). The manuscript has been digitized here. It contains a compilation of Catalan verse dating to 1461–1462. It is the oldest know manuscript to transmit Ausiàs March’s poetry, and an important witness to the transmission of the poetry of several other authors, including Pere Torroella and Lleonard de Sors.

About this Edition

I have reproduced and rendered in English two sonnets from the Hécatombe for which no other translation appears to be available, with notes indicating places in the text where the author has crossed out initial words and added new ones (I follow Henri Weber’s 1960 critical edition of the Printemps in this regard). The present transcription is based on the manuscript holding entitled ‘Théodore Agrippa d’Aubigné. Le Printemps et divers textes’ in the Archives Tronchin 157 at the Geneva Public Library (Bibliothèque de Genève). This manuscript can be consulted here. The folio numbers for the translated sonnets are f.77v-78. Other manuscript exemplars of this work can be found in the Bibliothèque de la Société de l’Histoire du Protestantisme Français (ms.816/12), and in the aforementioned Archives Tronchin 159.

Further Reading

Kuperty-Tsur, Nadine. “The Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre and Baroque Tendencies in France: The Impact of Religious Turmoils on the Aesthetics of the French Renaissance.” Poetics Today, translated by Sam W. Bloom, vol. 28, no. 1, (2007): 117–142., doi:10.1215/03335372-2006-017.

- A look at the influence of the Wars of Religion on Early Modern French poetry in general, and on a poem from Le Printemps in particular.

Nazarian, Cynthia Nyree. “Martyrdom, Anatomy, and the Ethics of Metaphor in d’Aubigné’s L’Hécatombe à Diane and Les Tragiques.” Love’s Wounds: Violence and the Politics of Poetry in Early Modern Europe, Cornell University Press, 2016, pp. 117–179.

- An examination of civil war violence reflected in love poetry.

Perry, Kathleen A. “A Re-Evaluation of Agrippa d’Aubigné’s « Printemps »: Youthful Love or Mature Theology?” Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance, vol. 51, no. 1 (1989): 107–122.

- Argues for the consideration of the poems of the Printemps as condemnations of the Catholic Church.

Perry, Kathleen A. “Motherhood and Martyrdom in the Poetry of Théodore Agrippa d’Aubigné.” Neophilologus, vol. 76, no. 2 (1992): 198–211, doi:10.1007/bf00210169.

- An analysis of the effects of d’Aubigné’s turbulent childhood on the representation of women in his poetry, with particular reference to the parallels drawn between Diane Salviati and the hunter goddess Diana/Artemis of classical lore.

Perry Long, Kathleen A. “Victim of Love: The Poetics and Politics of Violence in ‘Le Printemps’ of Théodore Agrippa d’Aubigné.” Translating Desire in Medieval and Early Modern Culture, edited by Craig A. Berry and Heather Richardson Hayton, Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies Press, 2005, pp. 31–47. Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies.

- An exploration of Petrarchan and Catullan aspects of d’Aubigné’s early poetry.

The Spring – The Hecatomb for Diane, VI | Le Printemps – L’hécatombe à Diane, VI

Hardy, j’entreprendray bravement de te rendre eternelle

Targuant de mes escrips ton nom contre la mort

Mais en t’eternisant, je ne travaille fort

Ta perfection n’est en aucun poinct mortelle

5 Rien n’est mortel en toy ta chasteté est telle

Que le temps envieux ne luy peut faire tort

Tes dons thresors du Ciel, ton Nom exemptz du port

Et du fleuve d’oubly ont la vue immortelle.

Mesmes ce livre heureux vivra infiniment

10 Pource que l’infiny sera son argument

Or ie ren graces aux Dieux de ce que i’ay servie M Toute perfection de grace & de beauté

Mais ie me plein à eux que ta severité

Comme sont les vertus, aussi est infinie

The Spring – The Hecatomb for Diane, VI

Boldly I will undertake to render you eternal,

Shielding* with my writing your name against death;

But in eternalizing you, I need barely work*:

Your perfection is in no way mortal.

5 Nothing in you is mortal, and your chastity is such

That jealous time cannot do it wrong.

Your gifts, treasures from Heaven, your name, exempt from the port

And from the river of forgetfulness, have immortal life.

Even this happy book will live infinitely

10 For the infinite will be its subject.

However, I thank the Gods for that which I have served:

All perfection of grace and of beauty;

But I bemoan to them that your severity,

Like your* virtues, is also infinite.

Critical Notes

Line 2: From the Middle French “targe” meaning “shield”.

Line 3: Literally “I do not work hard”.

Line 14: Literally “the virtues”, but I have changed this to a personal pronoun in English.