Regarding an outrageous incident at the University of Paris | De enormis casu in Universitate Parisiensis

“Conclusions de la Nation d’Angleterre. « Anno Mo CCCCo sexto, die quinta mensis maii — Mo CCCCo XXIIII, die septima mensis martii »”, NuBIS (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne)

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

Composed in Paris in early 1413, this Latin passage comes from a book written by the proctors of the English/ German Nation at the medieval University of Paris. Medieval European universities were often organized into a number of ‘Nations’ (nationes), semi-independent associations which grouped together students and masters on a broadly geographical basis. The University of Paris had four Nations: the French, the Picard, the Norman, and the English/German one. Compiled by the proctors (elective officials) of the Nations, the ‘books of the proctors of the Nations’ (libri procuratorum nationis) were registers containing chronological entries which documented any significant information about the academic, social, and political life of each Nation and of the university in general. Needless to say, these are sources of unparalleled value when studying early universities.

The author of this passage is Johannes de Reno, a master of the University, who was proctor of the English/German Nation at the time. The writing style is simple and almost rushed, reflecting the practical character of proctors’ books. The passage recounts the events surrounding a curious incident which occurred between the scholars of the Collège d’Harcourt and the host of a nearby Parisian lodging house in late 1412. After one of the lodging house’s horses is found dead in front of the Collège, some students repeatedly visit the house and ask for the carcass to be removed, but to no avail: the host ridicules them in vulgar fashion. The angry students drag the carcass back to the lodging house themselves. Later, in the middle of the night, some of the lodging house guests and other Parisian burghers attack the Collège and a violent fight ensues. The situation is ultimately resolved through the intervention of the Provost.

This text is interesting because it exemplifies the adversarial relationship between ‘town’ and ‘gown’, i.e. between local residents and members of the university community, in the city of Paris. It can also shed light on the impact of political developments on the university community. The events it describes took place during the Hundred Years’ War and the Armagnac-Burgundian Civil War, during which Normandy had proven to be a troublesome region. The attack by the lodging house guests appears to have been motivated, at least in part, by political resentment towards the Normans: the attackers single out the Norman residents of the Collège and call them “traitors to the King, the Kingdom, and the Duke of Burgundy!”

Introduction to the Source

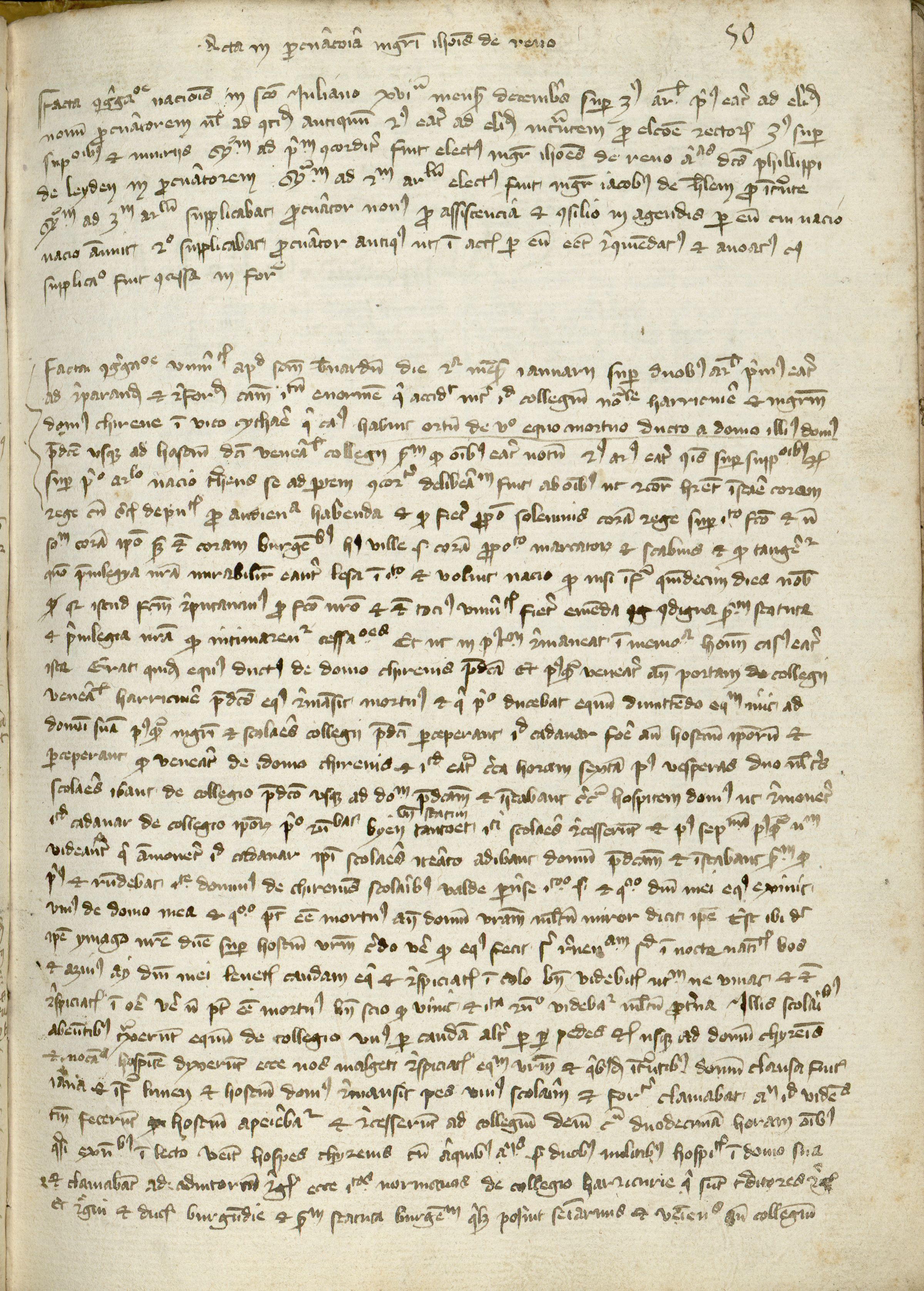

The original manuscripts of the English/German Nation of the University of Paris are currently kept at the Bibliothèque de la Sorbonne in Paris. Most of the Nation’s records from the 14th and 15th centuries survive. This passage is found in Reg. 5, ff.50r-v.

Further Reading

Green, David. The Hundred Years War: A People’s History. Yale University Press, 2014.

- A recent work on the political events that form the backdrop to the passage.

Kibre, Pearl. The Nations in the Mediaeval Universities. Medieval Academy of America, 1948.

- The standard work on the topic of medieval “nationes”; it focuses mostly on their institutional history.

Schwinges, Rainer C. “Student Education, Student Life.” A History of University in Europe, edited by Hilde de Rid-der-Symoens, vol. I, Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 195-243.

- A good introduction to various issues relating to student life in medieval universities.

Skoda, Hannah. Medieval Violence: Physical Brutality in Northern France, 1270-1330. Oxford University Press, 2013.

- A fresh look at scholarly violence from the passage’s period, with plenty of examples.

Regarding an outrageous incident at the University of Paris | De enormis casu in Universitate Parisiensis

Facta congregacione Universitatis apud Sanctum Bernardum die secunda mensis Januarii super duobus articulis. Primus erat ad reparandum et reformandum casum instum enormem, qui accidit inter illud collegium notabile Harricurie et magistrum domus Chirene in vico Cythare qui casus habuit ortum de uno equo mortuo ducto a domo illius domus predicte usque ad hostium dicti venerabilis collegii, secundum quo omnibus erat notum. […] Et ut in posterum remaneat in memoria hominum, casus erat iste.

Erat quidam equus ductus de domo Chirenis predicta, et postquam venerat ante portam collegii venerabilis Harricurie, predictus equus remansit mortuus, et qui primo ducebat equum, dimittendo equum ivit ad domum suam. Postquam magistri et scolares collegii predicti perceperant illud cadavar fore ante hostium ipsorum, et perceperant quod venerat de domo Chirenis, et istud erat circa horam sextam post vesperas duo vel tres scolares ibant de collegio predicto usque ad domum predictam et instabant circa hospitem domus, ut removeret istud cadavar de collegio ipsorum.

Primo respondebat: “byen, tantoct.” Isti scolares recesserunt, et post septimam, postquam nullum viderant qui ammoveret illud cadavar, ipsi scolares iterato adibant domum predictam et instabant secundum quod prius. Et respondebat iste dominus de Chirenis scolaribus valde perverse isto modo scilicet: “Et quomodo, domini mei, equus exivit vivus de domo mea, et quomodo potest esse mortuus ante domum vestram, multum miror; est ibi, dicit ipse, ymago nostre Domine super hostium vestrum; credo vere quod equus fecit sibi reverenciam, sicud in nocte Nativitatis bos et azinus. Ay, domini mei, levetis caudam equi et respiciatis in culo, bene videbitis utrum ne vivat, et eciam respiciatis in ore; vere non potest esse mortuus. Bene scio quod vivit.”

Et ista responsio videbatur multum proterva illis scolaribus abeuntibus, [qui] traxerunt equum de collegio, unus per caudam, alter per pedes, etc., usque ad domum Chyrenis, et vocando hospitem dixerunt: “Ecce nos, Malgeti, respiciatis equum vestrum”. Et quibusdam intrantibus domum clausa fuit janua, et infra limen et hostium domus remansit pes unius scolarium, et fortiter clamabat. Alii illud videntes tantum fecerunt, quod hostium aperiebatur, et recesserunt ad collegium.

Deinde circa duodecimam horam, omnibus quasi existentibus in lecto, venit hospes Chyrenis cum aliquibus aliis, scilicet duobus militibus hospitibus in domo sua, et clamabant ad adjutorium regis: “Ecce istos Normanos de collegio Harricurie, qui sunt traditores regis et regni et duci Burgundie!” Et secundum statuta burgensium quilibet posuit se in armis, et veniens ante collegium quilibet clamabat: “frangatis hostia et muros” etc., et erant bene in numero armati CCC ante collegium illud, et fregerunt hostia et intraverunt clamantes “ad mortem”, et fregerunt bene viginti januas camerarum, et nullum reperiebant armatum in dicto collegio, […] et clamabant: “Ponamus ignem!” Et tunc veniebat prepositus Parysiensis et omnia disposuit ad melius. Et erant duo scolares de domo capti et duo fortiter volnerati.

Et iste est casus de quo prius tangebatur, quem in plena congregacione narraverunt duo magistri in theologya de collegio. Et concludebat nacio, quod iste hospes detineretur in carceribus, quousque nobis fieret emenda condigna.

On the second day of the month of January, the university congregation met at the Collège des Bernardins to discuss two matters. The first was the reparation and rectification of the outrageous incident which had occurred between the illustrious Collège d’Harcourt and the master of the Chirene house in rue de la Harpe. According to public knowledge, the incident originated with a dead horse brought from the house of the master of the said house to the entrance of the distinguished Collège. […] The facts of the incident are reported here so that they might remain in men’s memory in future.

A certain horse was led out of the Chirene house, and when it arrived in front of the door of the distinguished Collège d’Harcourt, it died; the person who was at first leading the horse went back to their house leaving the horse behind. After vespers, at around six o’clock, the masters and students of the Collège noticed the carcass in front of their entrance door and realised that it came from the Chirene house. Two or three students then went from the Collège to the said house and pressed its host for the removal of the carcass from their Collège.

At first the host replied: “Sure, immediately.” The students withdrew, and after seven o’clock, when they had not seen anyone moving the carcass, they went to the house a second time and repeated their request. And the master of the Chirene house replied to the students in this extremely wicked way: “My lords, I am greatly surprised at how it is possible that the horse left my house alive and is now dead in front of yours. There is an image of our Lord above your door; I sincerely believe that the horse was just paying reverence to it [by kneeling down] like the ox and the donkey on the night of the Nativity. Yes, my lords, if you lift the tail of the horse and look in its ass, you will clearly see whether it is dead, and look in its mouth too; it truly cannot be dead. I know very well that it is

This reply seemed very wicked to the students as they were walking off, and they therefore dragged the horse from the Collège all the way to the Chirene house, one by its tail, one by its hoof, etc., and as a way of summoning the host said: “Here we are, Malgeti, look at your horse.” And while they were entering the house the door was closed, and the foot of one of the students remained stuck in the strangers’ house, and [the student] was screaming loudly. Seeing this, the others managed to have the door reopened, and the students withdrew to the Collège.

Afterwards, at around midnight, when almost everybody was in bed, the host of the Chirene house arrived with some others, certainly with two soldiers who were guests in his house, and they were crying out for royal support: “Behold, the Normans of the Collège d’Harcourt, who are traitors to the King, the Kingdom, and the Duke of Burgundy!” And according to the statutes, every burgher armed himself, and going before the Collège was screaming: “Let’s break the doors and the walls” etc., and then there were three hundred well-armed people in front of the Collège, and they shattered the doors and entered, shouting “To death!”, and very much destroyed twenty room doors1, although they could not find anyone who was armed in the Collège, […] and they were shouting: “Set it on fire!” Then the provost of Paris arrived and redressed the situation. And two students were seized from the house, and two others were severely injured.

This is the incident which has been previously touched upon, which two masters in Theology from the Collège recounted before the entire congregation. And the Nation2 concluded that the host [of the Chirene house] should be detained in prison until an appropriate compensation had been made to us.

Critical Notes

-

That is, twenty internal doors within the Collège building.

-

The English/German Nation at the medieval University of Paris.