To the tune “River Town”—Hunting in Mizhou | 江城子 · 密州出獵

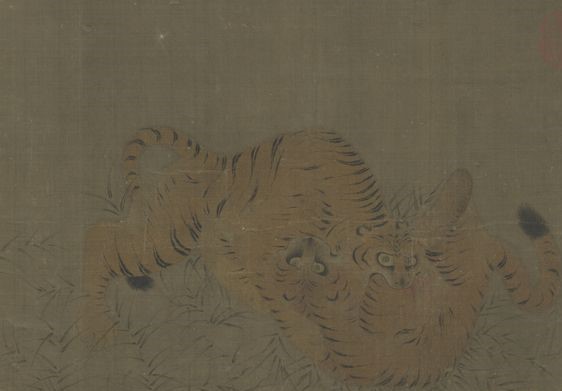

“Detail from 宋人卞莊子刺虎圖卷 (tiger)”, Anonymous, National Palace Museum, Accession Number: K2A001006N000000000PAB [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

This song was written in 1075 CE when the poet was prefect of Mizhou. The first stanza describes a hunting trip in which many local people participated: a sign of their respect for Su Shi. As a gesture of gratitude, Su Shi wishes he could undertake a heroic act like Sun Quan, a king who famously shot a tiger to prove his courage. In the second stanza, by comparing himself to Wei Shang, a famous Han Dynasty prefect who was once deprived of his official title but later had his position restored, Su Shi expresses both a desire to be recognized again by the imperial court, and a willingness to take on responsibility for defending the country’s frontiers. This song was written in 1075 CE when the poet was prefect of Mizhou. The first stanza describes a hunting trip in which many local people participated: a sign of their respect for Su Shi. As a gesture of gratitude, Su Shi wishes he could undertake a heroic act like Sun Quan, a king who famously shot a tiger to prove his courage. In the second stanza, by comparing himself to Wei Shang, a famous Han Dynasty prefect who was once deprived of his official title but later had his position restored, Su Shi expresses both a desire to be recognized again by the imperial court, and a willingness to take on responsibility for defending the country’s frontiers.

The ci genre of Chinese poetry first emerged in the Sui dynasty (581-619), was further developed in the Tang dynasty (618-907) and matured in the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127). Ci is usually translated into English as “song lyrics”. This is because ci were composed by poets to fit pre-existing tunes. The number of lines, the line lengths, and the tonal and rhythmic patterns of ci vary with the tunes, which number in the hundreds. One common occasion for composing ci would be a banquet: song lyrics would be scribbled down by guests and then sung by musical performers as entertainment. Other occasions for composing and enjoying ci would be more casual: the poet might sing the lyrics to himself at home or while travelling (many ci poets were civil servants of the Imperial Court and often had to travel great distances to carry out their work). Sometimes the lyrics would be sung by ordinary people in the same way as folk songs. This oral and musical quality sets it apart from other genres of poetry in China during the same period, which were largely written texts with more elevated objectives. There are two main types of ci : wǎnyuē (婉 约, “graceful”) and háofàng (豪放, “bold”). The wǎnyuē subgenre primarily focuses on emotion and many of its lyrics are about courtship and love, while the háofàng subgenre often deals with themes that were considered more profound by contemporary audiences, such as ageing and mortality, or the rewards and disappointments of public service.

Su Shi 蘇軾 is one of the most popular Chinese poets of all time, and certainly one of the best-known poets of the Song Dynasty. Among his many roles—principled politician, esteemed poet, celebrated calligrapher—he was also a major reformer of the ci genre. Before Su Shi, the primary form of ci was wǎnyuē (婉 约, “graceful”). This was considered to be an inferior form of literature due to its thematic focus on love and desire and its association with the courtesans who usually performed it. Su Shi wrote lyrics on a broad range of non-traditional topics, often closely related to his own life experience. His compositions dealt with themes that were considered more profound by contemporary audiences, such as ageing and mortality, or the rewards and disappointments of public service. As a pioneer of the háofàng (豪放, “bold”) type of ci, he incorporated references to typically masculine pursuits, including frequent use of a hunting motif. He also frequently incorporated ideas from Buddhist philosophy and allusions to political events, which usually appeared only in more elevated forms of poetry.

Although Su Shi was a highly-regarded poet during his lifetime, his political career was consistently unfortunate. In 1066, he was forced to leave the Court when he openly opposed the chancellor’s socio-economic reforms, known as the New Policies. Over the next thirteen years, he was frequently demoted, serving as prefect or sub-prefect in Hangzhou, Mizhou, Xuzhou and Huzhou. Many of his ci reference these postings and the exhaustion of constant travel. A report about the troubling economic conditions of local people written while he was prefect of Huzhou landed him in prison for three months. He was finally sent back to Hangzhou and given a job with no salary. Although living in poverty, he grew fond of Hangzhou and wrote many of his most famous ci there.

Because of the occurrence of specific real names and locations in Su Shi’s lyrics, as well as the introductory notes he wrote to accompany many of them, his lyrics often invite a biographical reading. This differentiates him from other ci poets featured in this collection, whose writings did not usually reference their own lives in such a direct way. Yet although Su Shi’s lyrics evoke specific lived experiences, the enduring popularity of his poetry is due, in part, to the fact that diverse audiences can identify with the feelings he describes.

About this Edition

The original text of this ci is based on the edition by Tang Guizhang 唐圭璋 ( Quan Song Ci 全宋詞, vol 1. Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju, 1965). Punctuation follows the edition. Since ci poetry rarely includes personal pronouns, and gender-differentiated pronouns did not exist in Classical Chinese of this period, the gender of the speaker as well as their perspective (e.g. first-, second- or third-person) must often be deduced by the translator from context.

Further Reading

Chang, Kang-i Sun. The Evolution of Tz’u Poetry: from Late Tang to Northern Sung. Princeton UP, 1980.

- A standard survey of the early history of Chinese song lyrics (romanized as both ci and tz’u).

Egan, Ronald. “The Song Lyric”. The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, vol. 1, edited by Stephen Owen, Cambridge UP, 2010, pp. 434-452.

- An overview of the genre.

Owen, Stephen. Just a Song: Chinese Lyrics from the Eleventh and Early Twelfth Centuries. Asia Center, Harvard UP, 2019.

- A recent new history of the genre.

Tang, Guizhang 唐圭璋, editor. Quan Song Ci 全宋詞. Zhonghua shu ju, 1965. 5 vols.

- A comprehensive edition of ci from the Song dynasty and the source text for the ci in this collection (introductions and annotations are in Chinese).

To the tune “River Town”—Hunting in Mizhou | 江城子 · 密州出獵

江城子 密州出獵

老夫聊發少年狂。

左牽黃。

右擎蒼。

錦帽貂裘,

5 千騎卷平岡。

爲報傾城隨太守。

親射虎,

看孫郎。

酒酣胸膽尚開張。

10 鬢微霜。

又何妨。

持節雲中。

何日遣馮唐。

會挽雕弓如滿月,

15 西北望,

射天狼。

To the tune “River Town” Hunting in Mizhou

I take on a young man’s arrogance for a moment,

pulling a yellow dog with my left hand,

and holding a goshawk with my right.

I am capped in brocades and clothed in a mink fur coat,1

5 and thousands of cavalrymen are sweeping the smooth hillside.2

To show gratitude to the entire town for following me hunting,

I will shoot the tiger myself,

like Sun Quan.3

As I drink to satisfaction, my chest opens and my courage is strengthened.

10 My temples are touched by frost,4

but why bother with that?

Feng Tang, who went to Yunzhong5 with a Fu Jie:6

when will the court dispatch him?7

By that time I will pull my carved bow into the shape of a full moon,

15 aim to the northwest,

and shoot down Sirius8.

Critical Notes

-

Refers to the typical hunting attire of a prefect at that time.

-

The speaker uses “thousands of” as an exaggeration to emphasize the size of his retinue and the grandeur of the occasion.

-

Sun Quan (182-252 CE) was the ruler of the State of Wu during the Three Kingdoms period (220-280 CE). He once pursued a tiger on horseback, managing to kill it even though it had bitten his horse. Here the

speaker compares himself to Sun Quan.

-

This implies that the poet is already old and has white hair at his temples.

-

Yunzhong was the name of a place in present-day Inner Mongolia.

-

During the Song Dynasty, a “Fu Jie” was a staff that symbolized the court’s pardon of an official.

-

The implication here is “When will the court dispatch Feng Tang to pardon Wei Shang?”, with the poet using Wei Shang to represent himself. The Prefect of Yunzhong, Wei Shang, successfully defeated the invading Xiongnu troops but was deprived of his official title because his battle report stated a number of enemies killed that was six fewer than the actual number. Feng Tang, a court official, defended the prefect and convinced Emperor Wen of Han (r. 180-157 BCE) that his sentence was too severe. The emperor thus sent Feng Tang to pardon the prefect and restore the latter’s title. Here the speaker refers to himself as the prefect and hopes to retrieve the court’s trust and favor. The order of the words in the original has been modified in the translation to make the sentence easier to understand. The literal translation of this line and the preceding line is: “Going into Yunzhong with a Fu Jie; / When will the court dispatch Feng Tang?”

-

In ancient China, “Sirius” was the name given to a star that was commonly believed to control warfare. “Shoot down Sirius” indicates the speaker’s wish to defeat major rivaling states, very likely the Western Xia in the north west, which was a great threat to the Northern Song court.