Noble prayer said when standing before kings, known by experience to be beneficial (God most high willing) | دعاء شريف يقال عند مقابلة الملوك نافع مجرب إن شاء الله تعالى

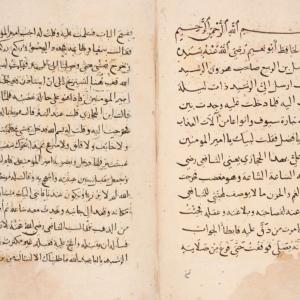

Khalidi Library (Jerusalem) MS 214, fol. 59v-60r [Courtesy of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

This text is attributed to Abū Nuʻaym al-Iṣbahānī (948-1038), and indeed a shorter version of the story can be found in Abū Nuʻaym’s biographical dictionary Ḥilyat al-awliyāʼ wa-ṭabaqāt al-aṣfiyāʼ (vol. 9, pp. 78-79 in the Beirut edition), which compiles biographical accounts of many early Islamic figures. This excerpt comes from the section on the foundational early legal scholar Muḥammad al-Shāfiʻī (d. 820), its central character, but has been substantially expanded and modified from Abū Nuʻaym’s original version, itself passed down from generations of earlier narrators. Abū Nuʻaym provides full chains of transmission (X said that Y said…) to authenticate each story, although in this version, the initial chain has been abbreviated on the assumption that the reader can seek out Abū Nuʻaym’s text for more complete information.

The accounts in Ḥilyat al-awliyāʼ emphasize the sanctity of early Muslims, and this one is no exception. The story is placed in the mouth of al-Faḍl ibn al-Rabīʻ (755-824), one of the most important court officials under the ʻAbbāsid caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd (r. 786-809). As al-Faḍl tells the story, he was summoned before the angry caliph one night and asked to produce al-Shāfiʻī for likely torture and/or execution. The reason for the caliph’s anger is not stated, but there is a historical nucleus to this event, for al-Shāfiʻī was nearly executed in 803, while he was governor of the rebellious city of Najrān. Different explanations have been given for the scholar’s narrow escape, including this account, which attributes his salvation to his pious recitation of a prayer at court. Through another, more complete chain of transmission, al-Shāfiʻī tells al-Faḍl that this prayer was recited by the Prophet Muḥammad during the Battle of the Trench (626-627) and contributed to the Muslims’ victory. Note that this connection to the Prophet is not found in Ḥilyat al-awliyāʼ, where the prayer is simply attributed to al-Shāfiʻī, but the expanded version amplifies its prestige. This text reflects the precarious, yet often luxurious, life of a powerful court official: you may be summoned before the caliph for torture, or you may instead receive more gold than you could ever need. One strategy for dealing with this precarity, as seen here, is to rely on the protection of God and recite this prayer each time the ruler calls your name.

As you read the text, note some of the distinctive features of classical Islamic texts, including:

-

The chain of transmission (isnād), already discussed, that provides authority for stories and sayings attributed to earlier figures. This text includes one incomplete chain and one complete chain.

-

Formulas of respect placed after the names of important people, such as “God’s peace and blessings be upon him” after a mention of the Prophet Muḥammad or “God be pleased with him” after a mention of al-Shāfiʻī.

-

Polite forms of address: the caliph is usually addressed as “Commander of the Faithful” (Amīr al-muʼminīn), while others are often called by names derived from their firstborn sons—for example, al-Shāfiʻī is often addressed as “Abū ʻAbd Allāh,” that is, “Father of ʻAbd Allāh.”

Introduction to the Source

This version of the prayer story is found only in Khalidi Library (Jerusalem) MS 214, fol. 59r-61v. The manuscript is not dat-ed, but was likely copied around the 15th century. The elaborately decorated title page (the style may indicate that it was produced in Egypt) describes the manuscript’s contents as “a compilation that contains aphorisms and testaments and fables by Luqmān the Sage.” The texts are a miscellany of popular philosophy, including the “Testament of Pythagoras” and the “Testament of Luqmān,” in which ancient philosophers allegedly give final instructions to their disciples before their deaths. The “Fables of Luqmān,” highly similar to those of Aesop, are also included. Various other sayings attributed to ancient philosophers appear between these larger texts, along with the inscriptions that were supposedly found on the philosophers’ seals. The story of al-Shāfiʻī and his prayer is the final item in the manuscript.

At first glance, the story of the prayer is an outlier in this compilation of texts attributed to ancient philosophers, focusing on specifically Islamic characters and themes as none of the other texts do. However, we may view the entire manuscript as a collection of short texts that would be interesting and beneficial for a court official to know, collected by just such an official (perhaps in Mamlūk Egypt) with money to spend on an ornate manuscript. Pithy sayings attributed to ancient sages and entertaining animal fables with succinct moral lessons would not only be edifying for the manuscript’s owner personally, but could be useful bits of knowledge as the owner aimed to impress superiors with erudite conversation top-ics. This prayer (and its enjoyable frame story) fits perfectly in that court context, and so we might view this manuscript as an anthology in the tradition of adab (“etiquette”) literature, training its reader in the proper knowledge and protocols for a refined member of the upper class. The context of Khalidi MS 214 thus recasts the text to make it less about the personal sanctity of al-Shāfiʻī, as in Ḥilyat al-awliyāʼ, and more about the elite readers who might rely on this prayer for protection in a precarious world.

About this Edition

I have transcribed and translated the text from Khalidi MS 214, its only known copy in this form. I have generally main-tained the spelling of the manuscript, including frequent omission of the Arabic letter hamzah (ء) that marks the glottal stop, but have standardized the dots on several letters that sometimes appear without them. The manuscript includes a surprising number of short vowel and case markings, but these have been omitted in transcription. There are few punctu-ation marks in the text, as with most pre-modern Arabic texts, and I have added a few additional periods to help organize the sentences. I have retained masculine language for God to reflect the usage of the Arabic text.

Further Reading

Ali, Kecia. Imam Shafi’i: Scholar and Saint. Oneworld Academic, 2011.

- Short biography of al-Shāfiʻī, the main character of this text.

Gutas, Dimitri. Greek Philosophers in the Arabic Tradition. Routledge, 2016.

- Collected essays showing some of the ways ancient philosophers were known and used in Arabic.

Kadi, Wadad. “The Humanities through Islamic Eyes: The Beginnings.” Knowledge and Education in Classical Islam: Reli-gious Learning between Continuity and Change, edited by Sebastian Günther, vol. 1. Brill, 2020, pp. 43-58.

- Overview of some important genres of classical Islamic scholarship, including the biographical dictionary.

Mojaddedi, Jawid A. The Biographical Tradition in Sufism: The Ṭabaqāt Genre from al-Sulamī to Jāmī. Curzon, 2001.

- Discussion of Ḥilyat al-awliyāʼ (especially in chapter 2) and other important Sufi biographical dictionaries.

Orfali, Bilal. “The Art of Anthology in Premodern Arabic Literature.” The Anthologist’s Art: Abū Manṣūr al-Thaʻ’ālibī and His Yatīmat al-dahr. Brill, 2016, pp. 1-33.

- Study of classical adab anthologies that may provide some inspiration for the collection of short texts in this manu-script.

Noble prayer said when standing before kings, known by experience to be beneficial (God most high willing)” | “ىلاعت هللا اش نا برجم عفان كولملا ةلباقم دنع لاقي فيرش اعد”

ميحرلا نمحرلا هللا مسب

عيبرلا نب لضفلا ىلا هدنسب هنع هللا يضر ميعن وبأ ظفاحلا ىور لاق هنا ديشرلا نوره بحاص

تدجو هيلع تلخد املف هيلا ترضحف ةليل تاذ ديشرلا يلا لسرا باذعلا تالآ نم اعاوناو فويس ةرابص هيدي نيب

يزاجحلا اذهب يلع لاقف نينموملا ريما اي كيبل تلقف لضف اي لاقف بضغم وهو ةعاسلا ةعاسلا هنع هللا يضر يعفاشلا ينعي

يضر يعفاشلل يتبحمل فصوي ال ام نزحلاو مغلا نم يبو تجرخف هلقعو هتغالبو هتحاصفل هنع هللا

هنأ تملعف باوجلا أطباف هيلع قد نم ترماف هباب ىلا تئجف هتالص نم غرف ىتح تفقوف يلصي

.نينموملا ريما بجا هل تلقو هيلع تملسف بابلا حتفف

.ةعاطو اعمس لاقف

رتسلا ىلا انلصو ىتح يشمي جرخو نيتعكر عكرو ءوضولا ددجف

تلخدف نذاتسا نا ىلا حيرتستل انه فق هللا دبع ابا اي هل تلقف هبضغ ةلاح ىلع وه اذاف نينموملا ريما ىلع

لوخدلاب هرم لاق رتسلا دنع تلق يزاجحلا نيا لاق ينار املف

هللا مسب هل تلقو هيلا تجرخف

ادب مث جعزنم الو قلق الو فئاخ الو عزف ريغ انئمطم يشمي لخدف رينتسم ههجوو هيتفش كرحي

لبقي لعجو هلبقتساو هيلا ماق نينموملا ريما هب رصبو لخد املف نوكتو انرزت ال مل هللا دبع يبأب ابحرم هل لاقو هب جهتباو هينيع نيب قاتشم كيلا ينناف اندنع.

ةردبب هل رمأ مث ةعاس هعم ثدحتو هبناج ىلا دعقو هناكم هسلجاو بهذلا نم

جلاو هلبقي نا هلأسف هيف يل يأر ال هنع هللا يضر يعفاشلا لاقف هب ثرتكم ريغ هلبقف هيلع

كتكرب نم لاننل الا كانبلط ام هللا دبع ابا اي ديشرلا هل لاق مث كتدهاشمب يظحنو

هيدي نيب ةردبلا لمحا ناو هراد ىلا هدرأ نا ينرما مث

ىتح الامشو انيمي هلأس نم لكو هآر نم لكيطعي لعج انجرخ املف اهنم ءيش هعم امو هلزنم ىلا لصو

هل تلقو هيدي نيب تسلج سولجلا هب نامطاو هلزنم لخد املف تدهاش يناو كيلع يتقفشو كل يتبحم تفرع دق هللا دبع ابا اي تيار هيلع تلخد امل مث كل هبلط ءادتبا يف نينموملا ريما بضغ ينرس ام كل ماركالاو لالجالاو ددوتلاو عضاوتلا نم هنم

هبضغ نكس يذلابف هيلع كلوخد دنع كيتفش كرحت كتيار تنكو هيلا يعم كلوخد دنع هلوقت تنكام ينتملع ام الا هرخسو

مهنعو هنع هللا يضر رمع نبا نع عفان نع كلام ينثدح لاقف بازحالا موي هارق ملسو هيلع هللا ىلص هللا لوسر نا نيعمجا وهو مهيلع هرصنو هللا مهمزهف

هللا دهش ميحرلا نمحرلا هللا مسب ميجرلا ناطيشلا نم هللاب ذوعا وه الإ هلإ ال طسقلاب امئاق ملعلا اولوأو ةكئالملاو وه الإ هلإ ال هنأ مالسإلا هللا دنع نيدلا نإ ميكحلا زيزعلا

هذهو ةداهشلا هذه هللا عدوتسأو هب دهش امب دهشأ انأو لاق مث ةميقلا موي ىلإ هللا دنع يل ةعيدو ةداهشلا

ةكربو كتراهط همظعو كتكرب ميظعو كسدق رونب ذوعأ مهللأ قرطي اقراط الإ راهنلاو ليللا قراوط نمو ةهاعو ةفأ لكنم كلالج ريخب

ذولأ كبف يذالم تناو ثيغتسأ كبف يثايغ تنأ مهللأ نمحر اي ريجتسأ كبف يراج تنأو ذوعأ كبف يذايع تنأو

ةنعارفلا قانعأ هل تعضخو ةربابجلا باقر هل تلذ نم اي

فارصنإلاو كركذ نايسن نمو كرتس فشكنمو كيزخ نم كب ذوعا كفنكتحتو كزرح يف انأ كركش نع

يتانكسو يتاكرحو يرافسأو ينعظو يداقرو يمونو يرانهو يليل يراثد كؤانثو يراعش كركذ يتاقوأو يتاعاس عيمجو يتاممو يتايحو

افيرشت كاوس دوبعم الو كريغ هلإ الو تنأ الإ هلإ ال نأ دهشأ افارتعاو كتينادمصل ارارقإو كهجو تاحبسل اميركتو كتمظعل نودحاجلاو نوملاظلاو نورفاكلا لوقي امع كل اهيزنتو كتينادحوب اريبك اولع كلذ نع تيلاعت

تاقدارس يلع برضاو كدابع رش نمو كيزخ نم ينرجأ مهللأ نيمحارلا محرأ اي ريخب كنم يلع دجو كتيانعو كظفح

فيكمأ يلكوت كيلعو ماضأ فيكمأ يلمأ تنأو فاخأ فيكيهلإ يدامتعا رومألا لكيف كيلعو بلغأ فيكمأ يرخذ تنأو رهقأ

هللا وه لقب دنك ملاطو دصر دصارو دسح دساح لك هجو تبرض دحأ اوفك هل نكي ملو دلوي ملو دلي مل دمصلا هللا دحأ

لضفلا لاق

ددرتأ لزأ ملو هنع هللا يضر يعفاشلا نم تاملكلا هذه تظفحف الإ ديشرلا نوراه ىلع تلخد امو اديج اظفح اهتظفح ىتح هتيب ىلإ ةيشعو ةركب اهب توعدو اهتأرقو

يلع بضغ الو اموي يلع درح الو هركأ ام هنم تيأر تدع ام هللاوف هنع هللا يضر يعفاشلا ةكربو فيرشلا ءاعدلا اذه ةكربب

نيمأ فيرشلا ءاعدلا اذه ةكرب نم نيملسملا ىلعو انيلع داعأو

ملسو هبحصو هلأو دمحم انديس ىلع هللا ىلصو

Noble prayer said when standing before kings, known by experience to be beneficial (God most high willing)”

In the name of God, compassionate and merciful

Ḥāfiẓ Abū Nuʻaym, God be pleased with him, narrated with a chain of transmission from al-Faḍl ibn al-Rabīʻ—the companion of Hārūn al-Rashīd—who said:

Al-Rashīd sent for me one night, so I went to see him. When I entered before him, I found him with a number of swords and various instruments of torture.

He said, “Faḍl.” I said, “At your service, Commander of the Faith-ful.” He said, “Bring me this Ḥijāzī”—meaning al-Shāfiʻī, God be pleased with him—“this very hour!” And he was enraged.

So I left, filled with indescribable grief and sorrow because of my love for al-Shāfiʻī—God be pleased with him—on account of his eloquent way with words and his intellect.

I came to his door and commanded someone to knock, but he was slow to answer.

He opened the door and I greeted him and said, “Answer the Commander of the Faithful.

He said, “To hear is to obey.”

He renewed his ablutions, did two cycles of prayer, and left, walking until we reached the curtain.

I told him, “Abū ʻAbd Allāh, wait here and relax until I call you in.” I went in to the Commander of the Faithful, who was still angry.

When he saw me, he said, “Where is the Ḥijāzī?” I said, “At the curtain.” He said, “Command him to enter.”

So I went out and said to him, “In the name of God.”

He went in, walking serenely, neither dismayed nor frightened nor worried nor uneasy. Then he began moving his lips and his face was illuminated.

When he entered and the Commander of the Faithful saw him, he stood and welcomed him and began kissing him between the eyes. He was happy and said, “Welcome, Abū ʻAbd Allāh! Why have you not visited us, when you’re in town and I’ve been missing you?”

He had him sit in his place, sat next to him, and talked with him for a while, then ordered that he be given a huge quantity of gold.

Al-Shāfiʻī—God be pleased with him—said, “I have no interest in it.” But he asked him to accept it and kept pestering him, so he accepted it with indifference.

Then al-Rashīd said to him, “Abū ʻAbd Allāh, we only summoned you to obtain some blessing from you and to gain an audience with you.”

Then he commanded me to return him to his home and to take the gold along.

When we went out, he began to give it to everyone he saw and everyone who asked, left and right, until he arrived at home and none of it remained.

When he had entered his home and was sitting peacefully, I sat before him and said, “Abū ʻAbd Allāh, you know my love and af-fection for you. I saw the anger of the Commander of the Faith-ful when he first summoned you, then when you went before him, I saw his humility and friendliness, treating you with an honor and deference that delighted me.

I saw you moving your lips when you went in before him, so what else could have calmed his anger and contempt? Teach me what you were saying when you and I went in before him.”

He said, “Mālik reported to me from Nāfiʻ, from Ibn ʻUmar—God be pleased with him and with them all—that the Messenger of God—God’s peace and blessings be upon him—recited it on the Day of the Confederates, so God routed them and gave him vic-tory over them. It is:

“I seek refuge in God from Satan the damned, in the name of God, merciful and compassionate. ‘God testifies that there is no god but him—as do the angels and those with knowledge—upholding justice. There is no god but him, Mighty and Wise. Religion in the sight of God is Islam.’1

Then he said, I also testify to what he has testified, and I place this testimony as a deposit with God. This testimony is my de-posit with God until the day of resurrection.

God, I seek refuge in the light of your holiness, the power of your blessing, the greatness of your purity, the blessing of your majesty, from every harm and malady and the misfortunes of night and day, that the traveler may arrive safely.

Merciful God, you are my help, so I seek help with you! You are my shelter, so I seek shelter with you! You are my refuge, so I seek refuge with you! You are my protection, so I seek protec-tion with you!

You, before whom the necks of tyrants are humbled and to whom those of pharaohs submit!

I seek refuge in you from disgrace before you, from the opening of your veil, from forgetting to remember you, from neglecting to give you thanks. I am in your sanctuary, beneath your wing.

My night and my day, my sleeping and my lying down, my setting out and my traveling, my moving and my resting, my living and my dying, and all of my hours and times, your remembrance is on my lips and your praise covers me.

I testify that there is no god but you, there is no god beside you, there is no one worshiped except you, exalting your greatness, honoring the glory of your face, declaring your eternity and con-fessing your oneness, affirming that you are above all that the unbelievers and the unjust and the deniers say of you. You are highly exalted above that!

God, protect me from disgrace before you and from the wicked-ness of your slaves! Pitch for me the pavilions of your preser-vation and your providence! Generously grant me your blessing, most merciful of the merciful!

My God, how can I fear, when you are my hope? How can I be harmed, when my trust is in you? How can I be overcome, when you are my treasure? How can I be defeated, when I rely upon you in all things?

I strike the face of every envier who envies, every watcher who watches, everyone unjust and ungrateful, with ‘Say: He is God the one, God the eternal, he does not beget and he is not begot-ten, and there is none equal to him.’”2

Al-Faḍl said:

So I memorized these words from al-Shāfiʻī - God be pleased with him — and I did not stop returning to his house until I had memorized them well, and I never went in before Hārūn al-Rashīd without reciting them and praying them, morning or evening.

By God, I no longer received anything unpleasant from him, he was not annoyed with me for even a day, and he was never an-gry with me, by the blessing of this noble prayer and the bless-ing of al-Shāfiʻī, God be pleased with him.

May the blessing of this noble prayer continue to be upon us and upon the Muslims, amen.

God’s peace and blessings be upon our lord Muḥammad and his family and companions.

Critical Notes

Note 1: Qurʼan, Āl ʻImrān 3:18-19.

Note 2: Qurʼan, al-Ikhlāṣ 112.