Wandering lost, it was already night | Andando perdido, de noche ya era

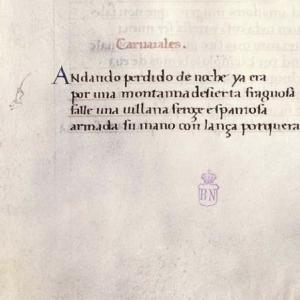

Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España MS, VITR/17/7, f.138r [Public domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

This poem is a serranilla, an evolution of the Provençal pastorela. Written in short verse ( arte menor), serranillas narrate a courtly poet’s encounter with a mountain woman. This is one of six compositions in the genre by fifteenth-century author Carvajal (or Carvajales). Very little is known about Carvajal’s life. His poetry is linked to the Neapolitan court of Alfonso the Magnanimous in Naples (r. 1442-1458) and to that of Alfonso’s son Ferrante (r. 1459-1494). In addition to his famous serranillas, Carvajal is also known for his literary epistles and ballads.

In this poem, the poet meets a fierce-looking wild woman who surprisingly offers courtly advice to the love-afflicted poet. It has been interpreted as a burlesque gloss of Juan Ruiz’s Libro de buen amor, one that conflates the serranas episodes with the discourse on dueñas chicas (‘little women,’ stanzas 1606-1617). The Libro de buen amor (1330/1343) is one of the masterpieces of medieval Castilian literature, a heterogenous, polysemous and oftentimes parodic text in which the narrator gives an account of his love life.

Introduction to the Source

The poem is copied in Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, VITR/17/7, fol. 136v-137r. This manuscript is a copy of the poetry collection known as the Cancionero de Estúñiga , ca. 1465. It has been digitized: http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000051837. It contains a compilation of mostly Castilian poems, including ballads, as well as a few Italian compositions. Their authors accompanied the King of Aragon, Alfonso the Magnanimous, in Naples in the mid-fifteenth century.

About this Edition

The text has been punctuated. Word separation and capitalization follow modern usage. Elisions have been marked with an apostrophe.

Further Reading

Carvajal. Poesie. Edited by Emma Scoles. Edizioni dell’Ateneo, 1967.

- Critical edition of Carvajal’s poetry.

Gerli, E. Michael. “Chapter 6. The Libro in the Cancioneros.” Reading, Performing, and Imagining the ‘Libro del Arcipreste’.

University of North Carolina Press, 2016, esp. pp. 194-203.

- Reassessment of Caravajal’s serranillas in view of their intertextual relationship with the Libro de buen amor.

Marino, Nancy F. La serranilla española: notas para su historia e interpretación. Scripta Humanistica, 1987.

- Study of the serranilla genre, with attention to Carvajal’s poems in chapter 5.

Wandering lost, it was already night | Andando perdido, de noche ya era

Andando perdido, de noche ya era,

por una montanna desierta, fraguosa,

falle una uillana feroçe, espantosa,

armada su mano con lança porquera.

5 Tenia grand fuego cabe una fontana

y en veiendome luego syn otra peresa

rebuelta en el braço una capa de lana

saliome adelante con mucha ardidesa

disiendo: “Escudero, ¿quien soys?, ¿que quereys

10 por esta grand silua deshabitada?”

“Sennora, cruesa de mi enamorada

me trahe fuyendo aquí donde ueys.”

“La perfection de nosotras, mugeres,

es de los trese fasta quinse annos;

15 con estas se toman suaues plaseres

et todas las otras son llenas de engannos.

Por ende, sennor, sy pasa los ueynte

aquella por quien soys tanto penado,

sabed que seredes el mas padesciente

20 et syenpre os uereys ser menos amado.

“Amad, amadores, muger que non sabe,

a quien toda cosa paresca ser nueua,

que quanto mas sabe muger menos uale

segund por exemplo lo hemos de Eua,

25 que luego comiendo el frutto de uida,

rompiendo el uelo de rica ignocencia

supo su mal et su gloria perdida:

guardaos de muger que ha platica et scientia.

“Amad, amadores, la tierna hedat,

30 quando el tiempo requiere natura

‘questa non tiene ninguna crueldat

nin offende al amante luenga tristura.

Wandering lost, it was already night,

By a deserted and craggy mountain

I found a ferocious and hideous peasant woman

Her hand armed with a javelin lance.

5 She was tending a big fire near a fountain

And then when she saw me, without thinking twice,

Her arm swathed in a wool cape,

She stepped forward much bravely

And said: “Who are you, squire, what are you looking for

10 In this great uninhabited wood?”

“My lover’s cruelty, madam,

Has made me escape here where you see me.”

“Perfection in us women

Spans between our thirteenth and fifteenth year;

15 With such young women you will enjoy tender pleasures.

All others are full of deception.

So, sir, if over twenty years old is

She for whom you are suffering so much,

Know that you will continue to suffer the most

20 And will always feel less loved.

“Lovers, love a woman who does not know,

One to whom everything seems new;

The more a woman knows the less she is worth

As Eve exemplifies;

25 For after eating the fruit of life,

Breaking the veil of pleasant innocence,

She learnt her troubles and lost her glory:

Beware of women who have practice and knowledge.

“Lovers, love the tender age

30 When time calls for nature;

This age harbors no cruelty

Or afflicts a lover with enduring sadness.”