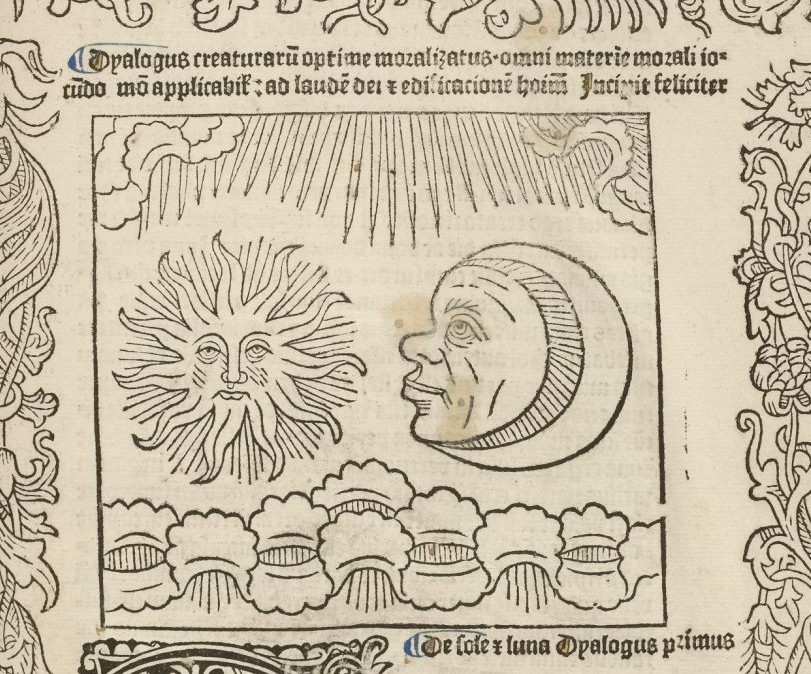

Concerning the Sun and the Moon | De sole et luna

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Arsenal, RESERVE FOL-BL-911, f.12r [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

The Dialogus Creaturarum (‘Dialogue of Creatures’), of which this text is one of eight published by the Global Medieval Sourcebook, was composed in the fourteenth century. Its authorship remains debated, though it was historically attributed to either Nicolaus Pergamenus, about whom little is known, or Magninus Mediolanensis (also known as Mayno de Mayneriis), who was a physician. In recent years, beginning with Pierre Ruelle in 1985, scholars have tended towards the conclusion that the Dialogus was compiled in Milan, though not necessarily by Magninus.

The text consists of 122 dialogues largely populated by anthropomorphic ‘creatures’, loosely defined; sections translated for the Global Medieval Sourcebook feature elements (fire, water), planetary bodies (the Sun, the Moon, Saturn, a cloud), animals (the leopard and unicorn), as well as a talking topaz. Each dialogue is further divided into two sections, the first part depicting an encounter between these creatures—two is the usual number, though some dialogues have one or three—that ends in a violent conflict. This experience is summed up in a moral, typically delivered by the defeated party, which is then exemplified in the second half of the dialogue through citations from historiography, literature, and sacred scripture. Common texts cited include the pagan authors Seneca the Younger and Valerius Maximus, along with the Christian writers Paul, Augustine, and John Chrysostom and compilations such as the Vitae patrum (‘Lives of the Fathers’) and Legenda aurea (‘Golden Legend’).

The great precision with which these references are cited—often including book and chapter numbers—suggests that the Dialogus was designed as a reference text containing recommendations for further reading, and more specifically as a handbook for ‘constructing sermons’ (as indicated in the Preface). This purpose does not, however, detract from its entertaining style, which derives in no small part from the passionate dialogue that takes place between the ‘creatures’ and the fast-paced descriptions of their battles against one another. These features explain the popularity of the Dialogus, which ran through numerous editions from the late fifteenth century onwards. The illustrated text compiled by Gerard Leeu was printed eight times in the eleven years from 1480 to 1491, once in French, twice in Dutch, and five times in Latin.

Introduction to the Source

Two manuscript versions of the Dialogus Creaturarum exist. Of these, only the so-called ‘short redaction’ has been printed. Gerard Leeu opted for this version of the text in the first Latin edition (1480), and all the vernacular translations are based upon it. The ‘short redaction’ is attested in twelve manuscripts from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, and is thought to best reflect the original text, which was composed after 1326. This dating derives from the fact that it borrows heavily from a compilation, the Libellus qui intitulatur multifarium, which was compiled at Bologna in that year (see Ruelle 1985, p. 22). In contrast, the ‘long redaction’ survives in only two manuscripts, both of which are comparatively late (in or after 1431): Toledo, Biblioteca Capitular, 10-28 and Torino, Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria, H. III. 6. In these manuscripts, the Dialogus Creaturarum is commonly presented under the title Contemptus Sublimitatis (‘The Contempt of Worldly Power’), which reflects its structure as a handbook of moral examples.

About this Edition

The source used for transcription and translation is Johann Georg Theodor Grässe’s 1880 edition, entitled Die beiden ältesten lateinischen Fabelbücher des Mittelalters: des Bischofs Cyrillus Speculum Sapientiae und des Nicolaus Pergamenus Dialogus Creaturarum (Tübingen: Literarischen Verein in Stuttgart). This edition can be accessed online here. Grässe bases his text on the 1480 edition by Gerard Leeu, which is itself most likely derived from several of the manuscript copies; for a full list, see Cardelle de Hartman and Pérez Rodríguez 2014, pp. 199-200. A late medieval printed version of the text, dating from 1481, is held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris and is available to view online here.

Further Reading

Cardelle de Hartman, Carmen, and Estrella Pérez Rodríguez. “Las auctoritates del Contemptus Sublimitatis (Dialogus Creaturarum).” Auctor et auctoritas in Latinis medii aevi litteris/Author and Authorship in Medieval Latin Literature: Proceedings of the VIth Congress of the International Medieval Latin Committee (Benevento-Naples, November 9-13, 2010), edited by Edoardo D’Angelo and Jan Ziolkowski, Florence: SISMEL - Edizioni di Galluzzo, 2014, pp. 199-212.

- Demonstrates that instead of nine manuscripts as previously thought, there exist fifteen complete manuscripts and a fragment, and outlines these manuscripts’ relationship to one another.

Kratzmann, Gregory C, and Elizabeth Gee, eds. The Dialoges of Creatures Moralysed: A Critical Edition. Leiden: Brill, 1988, pp. 1-64.

- Edition of the medieval English translation first published in 1530 (original author unknown), but the introduction contains information on the translation history and dissemination of the Latin Dialogus more generally.

Rajna, Pio. “Intorno al cosiddetto Dialogus creaturarum ed al suo autore.” Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 10, 1887, pp. 75-113.

- Advances arguments for two possible authors: Nicolaus Pergamenus and the Milanese doctor Mayno de Mayneriis, with a strong preference for the latter, and summarises the style and contents of the Dialogus.

Ruelle, Pierre, ed. Le “Dialogue des creatures”: Traduction par Colart Mansion (1482) du “Dialogus creaturarum’’ (XIVe siècle). (Classe des Lettres et des Sciences Morales et Politiques, Collections des Anciens Auteurs Belges, n.s. 8), Brussels: Palais des Académies, 1985, pp. 1-80.

- Annotated edition of the medieval French translation by Colart Mansion, but the introduction outlines the manuscript tradition and authorship of the Latin Dialogus.

Schmitt, Jean-Claude. “Recueils franciscains d’exempla et perfectionnement des techniques intellectuelles du XIIIe au XVe siècle.” Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes 135, 1977, pp. 5-21.

- Discusses the front matter in early manuscripts of the Latin Dialogus, which contained both a list of titles and an alphabetical index of moral lessons to facilitate citation.

Concerning the Sun and the Moon | De sole et luna

De sole et luna, dial. 1.

Sol est secundum philosophum oculus mundi, jocunditas dei, pulchritudo coeli, mensura temporum, virtus et origo omnium nascentium, dominus plantarum, doctor et perfector omnium stellarum. Luna vero, ut dicit Ambrosius in Exameron, est decor noctis, mater totius humoris et ministra, mensura temporum, dominatrix maris, immutatrix aëris et æmulatrix solis, et propter quod est æmulatrix solis, soli incepit detrahere et eum diffamare. Sol autem hoc sentiens loquutus est lunæ dicens: quare mihi detrahis et blasphemas? Ego semper te illuminavi et præcessi, tu autem semper me odis et impugnas.

Cui luna: recede a me, quia te non diligo, cum propter tuum magnum splendorem ego nihil appretior in mundo; si non esses, seculo superlata essem ego. Cui sol: ingrata sufficiat tibi magnificentia tua; si ego in die, tu vero in nocte perlustras. Obediamus ergo creatori nostro et noli superbire super me, sed me permitte lucere in die ac bona domini munire. Luna vero magis animata recessit cum furore et stellas ad se clamavit aggregavitque magnum exercitum et cum sole prœliari cœit. Sagittas enim mittebat adversus solem et cum jaculis percutere nitebatur.

Sol autem cum esset superius, descendit et lunam cum mucrone partitus est et stellas dejecit dicens: sie semper, cum eris rotunda, faciam tibi. Hac enim de causa, ut fabulæ dicunt, luna nunquam rotunda permanet et stellæ casum habent. Luna ergo coufusa in verecundia mansit dicens: turgidam melius partiri erat quam totam perire. Sic enim multi superbi et elati volunt sibi dominari nec superiorem vel similem cupiunt habere. Unde glosa: superbia est elatio incensa quæ inferioribus despiciens superioribus et paribus satagit dominari. Nam velle quidem esse super omnes vituperabiliter malum est, sustinere alterum sibi similem gloriosum est, ut ait Chrysostomus. De talibus enim dicit poeta: tolluntur in altum ut lapsu graviori cadant. Et nota, quod, quanto est major assensus, tanto est major et periculosior casus.

Concerning the Sun and the Moon, the first dialogue

Qui enim de plano et infimo loco cadit, cito resurgit, qui autem de alto, cito surgere nequit. Rami enim arboris, ut dicit Chrysostomus, qui staut in summitate, cito a magno vento franguntur, qui autem sunt ad radicem, conservantur. Unde etiam ait Quintus Curtius, quendam dixisse Alexandro quod, licet arbor magna crescat in altum, tamen vento citius exstirpatur, et licet leo tam sit superbus, tarnen parvarum avium efficitur cibus. Quidam philosopbus veniens ad sepulturam Alexandri ait: heri non sufficiebat isti totus mundus, hodie quinque sepultura pedum est contentus.

According to the philosopher, the Sun is the world’s eye, God’s delight, the beauty of the sky, the measure of time, the virtue and origin of all living beings, the lord of the plants, not to mention the teacher and perfecter of all stars. The moon, however, as Ambrosius says in his Exameron, is the night’s finery, the mother and servant of all liquids, the measure of time, the queen of the sea, the transformer of the air, and the imitator1 of the Sun. Since she had long been the Sun’s imitator, she began to withdraw from him and defame him. The Sun, sensing this, spoke to the Moon, saying, “Why do you pull me down, and blaspheme me? I have always illuminated you, and gone ahead of you; yet now you hate me and attack me.”

To whom the Moon answered, “Depart from me for I do not love you. After all, thanks to your great splendor, the world does not value me at all. If you did not exist, I would be extolled as the greatest being in the world.” In turn, the Sun responded, “Thankless creature, let your magnificence satisfy you. Indeed, I shine in the day, but you shine at night. Let us therefore obey our creator. Stop behaving arrogantly towards me, but allow me to shine during the day and guard over the good works of the Lord.” At this, however, the Moon drew back, even more incensed with fury. She called the stars to herself, assembling a great army, and began to battle with the Sun. She sent arrows against the Sun and strove to pierce him with darts.

Nevertheless, since the Sun inhabited a higher sphere, he simply descended and split the Moon with the point of his sword. Then, casting down the stars, he said, “Thus shall I always cleave you when you are full.” As the stories say, it is because of this that the Moon never stays full and the stars fall. The thwarted Moon wallowed in shame, saying: “It is better to be divided when overfull than to perish entirely.” In this way many of the proud and the powerful want to rule alone, and they desire to have neither superiors nor equals. Hence the following gloss: “Pride is incensed dignity which, despising inferiors, tries to rule over both superiors and equals. Indeed, to desire to outrank all others is horribly wicked, but it is glorious to hold another up as equal to oneself.” So says Chrysostomos. Concerning such matters, the poet says, “The exalted are raised up so that they can experience a more grievous fall.

Moreover, it is known that the greater one’s popularity is, the more perilous his fall will be. For he who falls from a flat and low place rises again swiftly, but he who falls from a height cannot rise again swiftly.” As Chrysostomus says, “The tree’s branches growing aloft are quickly broken by a great wind, but those at the root are saved.” Quintus Curius also relates that someone once said to Alexander, “Although a great tree might grow into the heavens, it will nevertheless be uprooted quickly by wind. Similarly, although a lion might be so proud, he will eventually be made into the food of small birds.” When arriving at Alexander’s tomb, one philosopher said, “Yesterday the whole world was not enough for this man. Today, he is content with his five-foot grave.”

Critical Notes

Translation

1 “Aemulatrix” is a play on words: not only “imitator”, which I have retained as the moon reflects the light of the Sun, but also “rival”.