The Song of Gutenberg | Gutenberglied

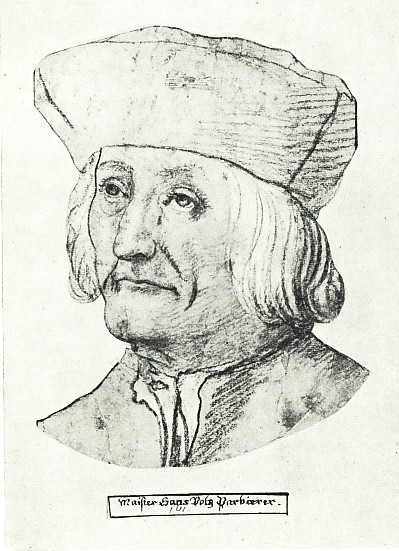

Portrait of Hans Folz by Hans Schwarz, c.1520. [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

The Gutenberglied (Song of Gutenberg) is a song composed sometime before 1480 by the Nuremberg poet and barber surgeon Hans Folz (ca. 1437–1513). The song is an example of the genre of the Meisterlied (master song), a form of art song prevalent in various German cities in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. These vernacular songs were typically created by artisans who composed new texts according to strict rules concerning rhyme, meter, and word choice. They set these texts to existing melodies and performed them in meetings of poets’ guilds.

This song is especially interesting as one of the earliest texts commenting on Johannes Gutenberg’s recent introduction in Europe of printing with movable type, which set the stage for the mass production and distribution of books, pamphlets, and other forms of printed works. Folz’s song is both supportive and suspicious of the new technology. Folz praises print for spreading the word of God, as print has made copies of the Bible more affordable for monasteries. However, he also criticizes it for allowing those who deny God—particularly the Jews—to spread their ideas. On balance, Folz concludes, print is a positive development and Gutenberg deserves praise for his invention.

Introduction to the Source

While Folz himself printed many of his own works (he operated his own small printing operation), he did not print this song (or any of his other master songs). The source survives in a late-fifteenth-century manuscript, possibly in Folz’s own hand, containing a number of Folz’s master songs, Shrovetide plays, and treatises on theology, fencing, and alchemy. The manuscript also contains a number of poems by the fourteenth-century poet Heinrich von Mügeln.

About this Edition

This translation is based on August Mayer’s 1908 edition of Folz’s master songs, available on Archive.org. I have maintained the original manuscript’s division of stanzas but have elected not to divide the transcription and translation into lines as the manuscript itself does not do this. I have also not attempted to recreate the rhyme scheme of the original German. The manuscript in which this song survives is available online on the website of the Duchess Anna Amalia Library in Weimar.

Further Reading

Baldzuhn, Michael. “The Companies of Meistergesang in Germany.” The Reach of the Republic of Letters: Literary and Learned Societies in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, edited by Arjan van Dixhoorn and Susie Speakman Sutch, Brill, 2008, pp. 219–55.

- Introduction to genre of master song.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. Divine Art, Infernal Machine: The Reception of Printing in the West from First Impressions to the Sense of an Ending. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

- Account of positive and negative reactions to print in early modern and modern Europe.

Flood, John L.. “Hans Folz zwischen Handschriftenkultur und Buchdruckerkunst.” Texttyp und Textproduktion in der deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters, edited by Elizabeth Andersen, Manfred Eikelmann, and Anne Simon, de Gruyter, 2005, pp. 1–28.

- This essay documents Folz’s printing career and contextualizes the Gutenberglied in Folz’s wider work as a printer. Includes a translation of the song into modern German.

Huey, Caroline. Hans Folz and Print Culture in Late Medieval Germany: The Creation of Popular Discourse. Ashgate, 2012.

- Study of Folz’s literary works and his work as a printer.

The Song of Gutenberg | Gutenberglied

Vor langer frist gesprochen ist von konig Salamone wie fort auff erd nicht newez werd nun ist sey[t] auß dem trone got komen und mensch worden hie daz doch seit waz ein newez ye ye doch ez die geschrifft vor hin besane

Daz aber sunst hie dise kunst puch drukes sey gewesen auff erden vor glaub ich nit zwor wer hat dar von gelesen doch west ez kunfftig got der werd allso ist doch nicht newz auff erd lob mit begerd sprecht im in seinen zesen

Was aber nucz und wider drucz von diser kunst bekomen do merket von: ein geistlich man hat in einr stim vernumen wie der entcrist in seinem dracz her nech in eim papiren schacz der nach dem gsacz vort wert der cristen frumen

Und mit dem dunst gancz fallscher kunst werd in der dewfel fullen / do von all schrifft in kaum furdrifft sein poz[ei]t zu verhullen daz macht groz straff, die er an went er meczelt martert wurkt und prent deupt und auch plent all die nit glauben wullen

Do wirt sulch schrifft im dan ein gift wider sein falsche rete wan waz allein und ungemein die schrifft von puchern hete do sint all stifft nun mit gezirt daz macht die cristenheit1 gefirt dar durch geirt wirt sulch deuflisch unstete

Ye doch so sprich ich sicherlich ein sach dunkt mich gar swere und driffet an geistlich persan die disen schacz der lere der heillgen schrifft um ringez gellt hie deutschen zu verfurn die wellt daz doch weit fellt ich furcht daz sint die mere

Dar von lang zeit man hot geseyt pristerschafft werd geschlagen wie kan ich daz glosiren paß dan allz ich ewch will sagen manch ley durch die ding wirt gemest mit puncktlin der er vor nit west und auff daz lest het numer taren fragen

Hin dan geseczt daz er mit letzt sich selbz und ander leien wan wie ez get allz ers verstet allso pfeifft er den reien do danczen dan die andern nach dar auß entspringen mag die schmach und sulche rach daz sich dan hept ein zweien

Und welch gelert daz dan erfert dem zimpt ez nit zu leiden die weil sint ein gewirczet fein sulch grund und warden schneiden in peiden orten sam ein swert und unerfert und welln der ding nit meiden

Und mellden frey ir soch dar pey, der glert nit sollten pflegen do durch wirt dan ydem sein man auff gleicher pan begegen dez rot ich furkumpt ez pey zeit daz geistlikeyt dar um nit leit legt ab den streit filleicht pleibtz unterwegen

Wan sulcher sam gepirt ein stam der poz ist auz zu rewten noch pringen mer sulch leiisch ler irung in schlechten lewten die juden wellens auch bekern und iren glauben falsch bewern unsern erclern und gruntlich war bedewten

Dar in sint zwar die juden gar poz narren ist mir rechte wie diser ley mit seim geschrey mit eim hat ein gefechte do ist der jud vor auff bewart und schneuczt im zaulich auff der fart durch sulche art wirt cristenheit geschmechte

Und auß gepreit von der judscheit dez haben schuld sulch doren der fantasey mer keczerey durch sulch unkunst mag foren ye doch schillt ich dez drukez nicht behender sin wart nie erdicht noch auch bericht dar durch in kurczen Jaren

Die cristlich ler so weiten wer in alle wellt entsprungen lob hab der erst got her der herst all er werd im gesungen dar nach dem ersten in dem werk juncker hansen von gutenberck die gotlich sterk gab daz der teutschen zungen

Der diß gedicht hat auß gericht der nent sich nit mit namen waz er sunst mach puchz flid scharsach sein narung pracht zu samen nun gib her daz er dich dort sech und daz uns allen daz geschech und unß nit schmech der hellisch feint sprecht amen

The Song of Gutenberg

Long ago King Solomon said that, from that moment on, there would be nothing new on earth. Since then, God has descended from His throne and become human, which was indeed something new, although the scriptures had foretold it.

I truly doubt that this craft of book printing has existed on earth before. Has anyone read about it? But God knew it would exist, so there is not anything new on earth. Praise him ardently in his eternal reign.

It is clear what usefulness and worry has come from this craft. A spiritual man has heard it said that the Antichrist, full of hate, would arrive in a trove of paper that the Bible claims is useful for the faithful.

And the Devil will fill him with the fumes of this perverted craft and everything that has been written will scarcely be enough to conceal his evil. He will punish us harshly: he will slaughter, torture, strangle and burn and deafen and blind all those who do not believe him.

But this writing will also be an antidote against his false proclamations because all monasteries are now adorned with all the books of the Bible. This makes Christianity strong and stands in the way of the Devil’s deceit.

And yet I say with confidence: there is one thing that I consider very alarming. It concerns men of the cloth who translate the valuable teachings of the holy scriptures into German for little money in order to lead the world astray. This is very wrong indeed. I fear these are the events

Which, it was foretold long ago, would harm the priesthood. How can I put it better than what I will now say to you: many a layman is, through these translations, being overburdened with details of which he previously knew nothing, and about which he would not have dared to ask.

Not to mention how he harms himself and other laymen with them, because this is how it goes: however he understands these details, he plays a merry tune and the others dance along. Outrage will come from this and such a call for vindication that a quarrel will begin.

And it would not behoove any scholar who finds out about this to suffer it lightly because such justifications have been dressed up nicely and the same sword will cut both ways those who are [passage missing] and inexperienced and do not want to avoid it.

And whoever freely announces their opinion, if scholars don’t care about it, will fight their opponents on an even playing field because of print. Therefore, I advise you: pre-empt this, and quickly, so that the priesthood doesn’t suffer because of it. Stop the fight! Perhaps it can still be avoided.

Because such a seed yields a tree-trunk that is hard to tear out of the ground. What is more, such lay teachings spread heresy among ordinary people. The Jews also want to convert people and falsely prove their beliefs, interpret ours and argue that theirs are true.

In this way, the Jews are hateful fools, I agree with this. How this layman1 started yelling and picked a fight with a Jew. This meant that the Jew was on his guard and sent him hurriedly on his way. Christianity is humiliated by such behavior.

And news of this humiliation is spread by the Jews. Those fools who are responsible for this have, in their ignorance, let their imaginations lead to heresy. Yet I don’t blame print. There has never been a quicker way to write texts and also to spread information. Because of this, within a few years

The message of Christ has spread far around the world. Above all, praise be to God most noble, praise be to Him! Praise be also to the inventor, Lord Hans von Gutenberg. The strength of God gave print to the German people.

He who wrote this poem will not be named. He earns a crust from his other pursuits, with his box of ointments2, his scalpel and his razor. Lord, let him see you in heaven, and grant this to all of us, and do not let the fiend from hell harm us. Say “Amen”.

Critical Notes

Transcription

-

The manuscript reads “xpnheit”, a common nominum sacrum for Christ.

Translation

-

It is unclear to whom Folz is referring here.

-

The German here is simply ‘puchz’—box, tin, canister. Given Folz’s main occupation as a barber-surgeon, this probably refers to a box of ointments or simple medicines.