To the tune “Spring in the Jade Building”—“In a tall building behind the willows by the lakeside” | 玉樓春 · 湖邊柳外樓高處

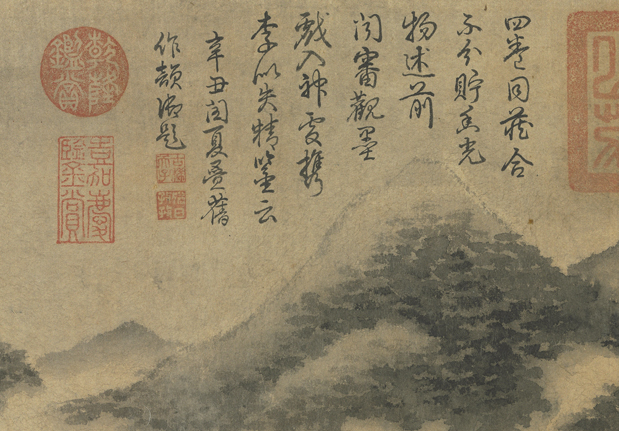

宋米芾雲山煙樹(Smoke and Trees) 卷 , 米芾, National Palace Museum, Accession Number: C2A000214N000000000PAH [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

This song lyric is a woman’s complaint about her lover. However, the two stanzas are quite different in tone and content. In the first, she sings wistfully of her longing; in the second, the focus shifts to her lover’s inconstancy.

The ci genre of Chinese poetry first emerged in the Sui dynasty (581-619), was further developed in the Tang dynasty (618-907) and matured in the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127). Ci is usually translated into English as “song lyrics”. This is because ci were composed by poets to fit pre-existing tunes. The number of lines, the line lengths, and the tonal and rhythmic patterns of ci vary with the tunes, which number in the hundreds. One common occasion for composing ci would be a banquet: song lyrics would be scribbled down by guests and then sung by musical performers as entertainment. Other occasions for composing and enjoying ci would be more casual: the poet might sing the lyrics to himself at home or while travelling (many ci poets were civil servants of the Imperial Court and often had to travel great distances to carry out their work). Sometimes the lyrics would be sung by ordinary people in the same way as folk songs. This oral and musical quality sets it apart from other genres of poetry in China during the same period, which were largely written

texts with more elevated objectives. There are two main types of ci : wǎnyuē (婉 约, “graceful”) and háofàng (豪放, “bold”). The wǎnyuē subgenre primarily focuses on emotion and many of its lyrics are about courtship and love, while the háofàng subgenre often deals with themes that were considered more profound by contemporary audiences, such as ageing and mortality, or the rewards and disappointments of public service.

Ouyang Xiu was a highly influential politician, scholar, and historian of the Northern Song dynasty. He was revered as a grand master of literature and philosophy, and it is not an exaggeration to say that he laid the foundation for the literati mentality of the dynasty. When Ouyang was four years old, the death of his father, a fifty-seven-year-old military officer, left the family destitute. Poverty did not stop Ouyang’s passion for reading: he would borrow books from his neighbors and make copies in order to study them further. Later, he became a bureaucrat and was posted to many cities as a prefect of the imperial court. In his political life, he was principled and solemn, and wrote a great deal in many genres. Much of his writing reflects his dignified character. His song lyrics, however, provide an interesting contrast. Their content may be drawn in part from the colorful private life he enjoyed in his younger years, including liaisons with many different courtesans. Interestingly, they are often written from the perspective of a lovelorn courtesan abandoned by an inconstant lover, in effect casting himself as the villain.

About this Edition

The original text of this ci is based on the edition by Tang Guizhang 唐圭璋 ( Quan Song Ci 全宋詞, vol 1. Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju, 1965). Punctuation follows the edition. Since ci poetry rarely includes personal pronouns, and gender-differentiated pronouns did not exist in Classical Chinese of this period, the gender of the speaker as well as their perspective (e.g. first-, second- or third-person) must often be deduced by the translator from context.

Further Reading

Chang, Kang-i Sun. The Evolution of Tz’u Poetry: from Late Tang to Northern Sung. Princeton UP, 1980.

- A standard survey of the early history of Chinese song lyrics (romanized as both ci and tz’u).

Egan, Ronald. “The Song Lyric”. The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, vol. 1, edited by Stephen Owen, Cambridge UP, 2010, pp. 434-452.

- An overview of the genre.

Owen, Stephen. Just a Song: Chinese Lyrics from the Eleventh and Early Twelfth Centuries. Asia Center, Harvard UP, 2019.

- A recent new history of the genre.

Tang, Guizhang 唐圭璋, editor. Quan Song Ci 全宋詞. Zhonghua shu ju, 1965. 5 vols.

- A comprehensive edition of ci from the Song dynasty and the source text for the ci in this collection (introductions and annotations are in Chinese).

To the tune “Spring in the Jade Building”—“In a tall building behind the willows by the lakeside” | 玉樓春 · 湖邊柳外樓高處

玉樓春

湖邊柳外樓高處。

望斷雲山多少路

闌干倚遍使人愁,

又是天涯初日暮。

5 輕無管系狂無數。

水畔花飛風裏絮。

算伊渾似薄情郎,

去便不來來便去。

To the tune “Spring in the Jade Building”

In a tall building behind the willows by the lakeside,

How many roads in the misty mountains have I stared to the end of?

I have leant against all the railings, feeling disheartened;

Again, the sun starts to set at the edge of the sky.

5 Light without being tied down, wild and numerous,

Petals fly beside the water, willow catkins are blown by the wind.

They are just like my fickle lover,

Leaving without returning, coming and soon departing.

Critical Notes

Line 5: The Chinese characters “管系 ” literally mean “discipline” and “obstacle”.