Copy of the riddle that was said to have been found in the temple of Saturn written on a golden tablet | نسخة اللغز الذي قيل انها وجدت في هيكل زحل مكتوبة في لوح ذهب

Hill Museum and Manuscript Library GAMS 00900

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

The rubric of this text explains its existence in the most dramatic way: it was purportedly found in the temple of Saturn (Arabic Zuḥal), written on a golden tablet, at some unspecified ancient date. The location of the “temple of Saturn” is also not specified, but we may assume that it is meant to be located somewhere in Iraq or upper Mesopotamia, perhaps in the city of Harran, famous in the early Islamic period for its lingering cult of astrological polytheism. The rubric next tells us that the text was later rediscovered in “ancient pages” and translated into Arabic by Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (ca. 809—873), an East Syrian Christian (member of the Church of the East) who became famous as the most important figure in the Baghdad translation movement that brought ancient philosophical and scientific texts into Arabic under the early ʻAbbāsid caliphs. The source language from which the riddle was translated is not stated, but is likely meant to be Syriac. Ḥunayn may in fact be responsible for the composition and/or translation of this text, but it is entirely possible that he is mentioned pseudonymously in order to associate the text with one of the most famous Christian scholars to write in Arabic. The text is accompanied by a commentary by ʻAmanúʼél d-Bét Garmay (d. 1080), an East Syrian metropolitan (archbishop) from northern Iraq (modern Kirkuk).

The rubric identifies the text as a “riddle” or “enigma” (lughz), but it fits uneasily in the context of other Arabic texts that use this term. Arabic riddles are generally written in an interrogative format and often in poetic meter, while this text is prose. There is no obvious “riddle” that could be answered here, but it seems the term is used to emphasize the cryptic nature of the text and its need for explanation, a task that ʻAmanúʼél attempts in his commentary. The riddle paints an apocalyptic picture that draws both on astrological references and on the story of Noah’s flood, especially in its Qur’anic form. It tells of a selfish king who decides, in a time of crisis, to pursue his own individual goals and abandon his kingdom to ruin. In the commentary, not included here, ʻAmanúʼél interprets the text as an allegory for the coming of Christ and the rise of Christianity, arguing that many philosophically-minded non-Christians have some awareness of Christian truth, even if they express it in different terms. The end of the commentary is lost, as noted by the scribe who copied this manuscript from an incomplete exemplar.

In addition to the fascinating frame story that is provided for this text, it is interesting for its apparent connection to nearly every major religious tradition of the early medieval Middle East, including less widely known traditions such as Harranian polytheism. Many Christians of this period were deeply aware of their non-Christian neighbors, and some of them drew on this knowledge to compose an enigmatic and intriguing text. Nevertheless, there has so far been little to no scholarly attention paid to the text.

Introduction to the Source

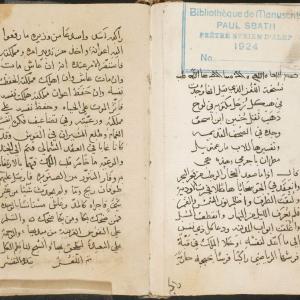

The sole known manuscript of the riddle is Fondation Georges et Mathilde Salem MS Syr 6, one of the hundreds of manuscripts collected by Syriac Catholic priest Paul Sbath (1887—1945) that remains in his hometown of Aleppo (formerly Sbath MS 900). It was copied in September 1684 and also includes an Arabic translation of The Book of the Dove by Bar Hebraeus (1226—1286), an important Syriac text on asceticism. The Arabic “Life of Moses the Ethiopian” (d. ca. 395) was copied separately and later bound with these texts. The entire volume is thus written in the Arabic language, but the vast majority of it is actually in Arabic Garshuni—that is, Arabic written in the Syriac script. Interestingly, the text of the riddle is copied in Arabic script, but the commentary on it is copied in Garshuni, making it easy to distinguish text and commentary visually. This may have been done to preserve the original form of the Arabic text associated with Ḥunayn, but it is not explained.

The scribe of this manuscript is Yūḥanná ibn al-Jarīr al-Zarbābī, who was a West Syrian priest (member of the Syriac Orthodox Church) in Damascus. This shows that al-Zarbābī was not limited to copying texts by members of his own church, like The Book of the Dove, but was interested enough in this riddle to copy it in spite of its association with two figures from the rival Church of the East.

The condition of the manuscript is unknown due to the lengthy civil war in Syria, but it was photographed in 2008 and digitized by the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML). It is available for viewing here. The text of the riddle appears on fol. 82v-83r and the commentary on fol. 83v-93v.

About this Edition

I have transcribed and translated the text from Salem MS Syr 6, its only known copy. I have generally maintained the spelling of the manuscript, including the usual omission of the Arabic letter hamzah (ء) that marks the glottal stop, but have standardized the dots on several letters that sometimes appear without them. The manuscript includes a surprising number of short vowel and case markings, but these have been omitted in transcription. The text repeated in the commentary sometimes differs slightly from the text given on its own, but I have tried to stick to the latter form insofar as it is legible and comprehensible. There are few punctuation marks in the text, as with most premodern Arabic texts, and I have added a few additional periods in order to help organize the sentences.

In addition to the commentary (not included here), the trinitarian invocation at the head of the text is written in Arabic Garshuni, which I have retained in transcription. I wrote the translation of this invocation in ALL CAPS as a way to mark the difference of script.

Further Reading

Bencheneb, M. “Lug̲h̲z.” Encyclopaedia of Islam. 2nd edition. Brill, 2012.

- Introduction to the Arabic riddle and closely related genres.

Green, Tamara M. The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran. Brill, 1992.

- Discussion of the unique religious context of this important city of upper Mesopotamia.

Griffith, Sidney H. The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam. Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Foundational introduction to the first few centuries of Christian life under Muslim rule and to the various Syriac and Arabic Churches.

Gutas, Dimitri. Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ʻAbbāsid Society. Routledge, 1998.

- Most influential discussion of the translation movement.

Copy of the riddle that was said to have been found in the temple of Saturn written on a golden tablet | نسخة اللغز الذي قيل انها وجدت في هيكل زحل مكتوبة في لوح ذهب

ܕܚܐܘ ܗܐܠܐ ܤܕܩܠܐ ܚܘܪܠܐܘ ܢܒܐܠܐܘ ܒܐܠܐ ܡܣܒ

بهذ حول يف ةبوتكم لحز لكيه يف تدجو اهنا ليق يذلا زغللا ةخسن

ةميدقلا فحصلا يف هدجو قحسا نبا نينح لقن

يه هذهو

اباحس وجلا يف دقعناو رحبلا رعق نم بطرلا راخبلا دعص ام اذا لاق ملف رمقلاو سمشلا رون ملظاو قرطلا تقثلو ةيدوالا ترجف الطاه اعدو ةنيدملا باوبا تقلغاو لبسلا تعطقناو راهنلا نم ليللا فرعي يضايرلا اهشرف ةبق يف كلملا الخو .هسفنل دعا ام ىلا سفن يذ لك هيلا اوعفر ام هريزو نم اعدتساو .دسا ةبكار ةيراج هبجحي اسرف ابكار شاع نا هنا هدنع رمالا رقتساف .هتكلممو هرما ريبدت نم ذخاو .هناوعا ظفح ناو هسفن تظفحنا هتكلمم كلها ناو شاع تام ناو تام هسفن ظفحو ةايحلا ىلع توملا رثاف .هسفن تكله هتكلمم ناوعا نارينملا علطو مامغلا عشقنا هركف فيعاضت يفو هتيعرو هتكلمم ىلع ام ةيعرلاو دنجلا ىلا متف .يلامشلا دقعلا يف اباغ اناك دقو سوقلا يف لسراف ةربونصلا نم رونتلا رافو .هب عافترالاب امهف كلملا بلق رماخ دملاك هارجاف يش ريغ نم ايش ثدحي ملو ءامو حير نافوط مهيلع ىلع ملسلاو .كحض اكب نمو اكب كحض نمف .ةدحولاب اسناتسم شاعو حبسلاو .اهب قحلتل ةديعبلا ىلع ةمحرلاو .اهيدبم نم ةبيرقلا سوفنلا لكلا مظانل

ريسفتلا هولتي .زغللا مت

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER AND THE SON AND THE HOLY SPIRIT, ONE GOD

Copy of the riddle that was said to have been found in the temple of Saturn written on a golden tablet

Translation of Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq, who found it in ancient pages

Here it is:

He said: When humid vapor rose from the depth of the sea and thickened in the air as clouds, coursing down so that the river-beds flowed, the pathways were turned to mud, and the light of the sun and the moon grew dark, so night was not known from day, the roads were cut off, and the gates of the city were closed, and everyone with a soul called upon what they had pre-pared for themselves.1 And the king secluded himself in a dome furnished with gardens, riding a horse that he kept hidden like a slave woman riding a lion. He asked of his vizier what his servants had set before him, and was taken up with the admin-istration of his affairs and his kingdom. Then it became fixed in his mind that if he lived he would die, and if he died he would live, and if he destroyed his kingdom, his soul would be saved, and if he saved the servants of his kingdom, his soul would be destroyed. So he preferred death over life, and saved himself rather than his kingdom and his subjects. Between the lines of his thought the clouds were scattered, and the two lights rose in Sagittarius after they had been hidden away in the northern node.2 Then what had seized the heart of the king came to pass for the army and the subjects, so they were being wiped out by it. And water gushed forth from within the oven,3 so he sent upon them a typhoon of wind and water, and nothing came from nothing, so he made it flow as a flood. And he lived on in inti-mate acquaintance with his own solitude. So whoever laughed wept, and whoever wept laughed. Peace upon the souls that are close to their Creator, and mercy upon those far away so that they might catch up to them, and glory to the one who arranges all things.

The riddle has ended. The commentary follows.

Critical Notes

Note 1: The Arabic word for “soul” (nafs) is used as a reflexive pronoun, so “themselves” could be translated “their souls” and vice versa.

Note 2: The “two lights” might reference the Sun and the Moon or possibly Jupiter and Saturn.

Note 3: A reference to the story of Noah’s flood as found in the Qur’an (see Qur’an 11:40 and 23:27).