Just as the elephant | “Atressi cum l’orifans”

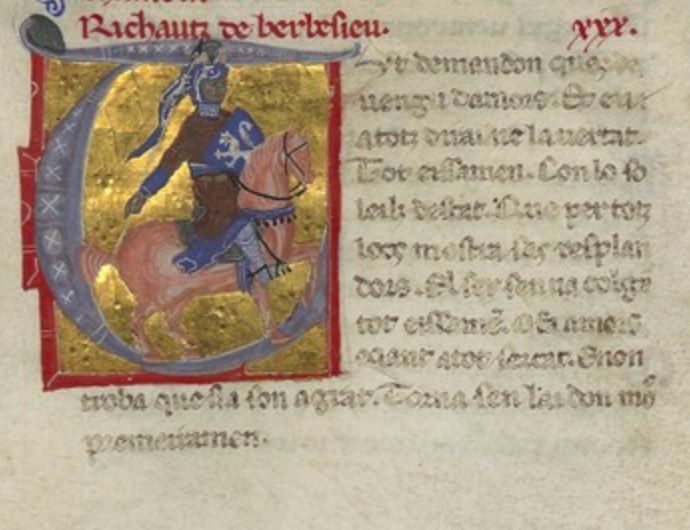

Life of Rigaut de Berbezilh in Paris BnF Fr. 12473 f.71r (Occitan Songbook K) [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

“Atressi cum l’orifans” (PC 421.2: “Just as the Elephant”) is a canso attributed to Rigaut de Berbezilh. There is contention as to when the troubadour was active: 1140–1157 or 1170–1210 (Varvaro 1960, 9-30). This lyric has attracted commentary because, like other songs by Rigaut, it relies on animal imagery to further the singer-lover’s rationale. If one dates Rigaut’s activity to 1140–1157, “Just as the Elephant” is one of the earliest Romance texts to attest to the circulation of such imagery, at times in direct connection with the Physiologus. The “I” likens himself to the elephant, the bear, the phoenix, and the stag, as well as Daedalus (who stands for Icarus). These animal images thematise the opposing or the conjoining of up and down, pain and improvement, death and revival, fleeing and returning, and are linked to the complex feelings of love that the “I” expresses. Amelia Van Vleck has discussed the way in which these elements, along with elements denoting spectacles or trials, are picked up by words denoting excess, such as “sobramar” (loving excessively) and “trop parlar” (speaking too much) (1993, 232).

The reference to the “cortz del Puey” (court of Puy) is one of the rare testimonies to the existence of a poetic contest in Puy-en-Velay. More generally, the poem emphasises the communal nature of the lover’s endeavour, supported as he asks to be by his fellow “fis amans” (refined lovers), and his ability to stand is dependent upon them. The reference to Daedalus also deserves mention because, although what is said about him applies to Icarus, it attests to some form of knowledge about Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Introduction to the Source

“Atressi cum l’orifans” is extant in a large number of manuscripts, which may indicate that when chansonniers were composed, Rigaut’s works were held in higher esteem than in scholarly assessments. Across manuscripts, the lyric changes, be it in the order of stanzas, the presence/absence of stanzas, single words and phrases, linguistic makeover, or the presence of a written melody (extant in two manuscripts). Rigaut seems to have been popular in Northern French chansonniers, although Eliza Zingesser has shown that this came at the cost of making Rigaut look birdlike, almost a madman (2020, 49–80).

This translation is based on the edition of the lyric by Carl Appel (1920, 70-71, item 29), with adapted punctuation. The reference edition remains that by Alberto Varvaro (1960, 106-134).

Further Reading

Appel, Carl, ed. Provenzalische Chrestomathie. Mit Abriss Der Formenlehre Und Glossar. 5th edition, Reisland, 1920. Rigaut de Berbezilh. Liriche, edited by Alberto Varvaro, Adriatica, 1960.

Van Vleck, Amelia. “Rigaut de Berbezilh and the Wild Sound. Implications of a Lyric Bestiary.” Romanic Review, vol. 84, nr. 3, 1993, pp. 223–40.

Zingesser, Eliza. Stolen Song. How the Troubadours Became French. Cornell University Press, 2020.

Just as the elephant | “Atressi cum l’orifans”

Atressi cum l’orifans

que, quan chai, no·s pot levar

tro l’autre ab lor cridar

de lor votz lo levon sus,

5 et ieu vuelh segre aquel us

quar mos mesfagz es tan greus e pezans

que, si la cortz del Puey e lo bobans

e l’adregz pretz dels leials amadors

no·m relevon, ia mais no serai sors;

10 que denhesson per me clamar merce

lai on preiars ni razos no·m val re.

E s’ieu per los fis amans

non puosc en ioy retornar,

per tostemps lays mon chantar

15 que de mi no y a ren plus;

ans viurai cum lo reclus,

sols, ses solatz, qu’aitals es mos talans,

quar ma vida m’es enuegz et afans

e gaugz m’es dols e plazers m’es dolors,

20 qu’ieu no suy ges de la maneira d’ors

que, qui be·l bat ni·l te vil ses merce,

adoncs engrayssa e melhuyra e reve.

Be sai qu’amors es tan gransqu/e,

que leu me pot perdonar,

25 s’ieu falhi per sobramar

ni renhey cum Dedalus,

que dis qu’elh era Jhezus

e volc volar al cel outracuians,

mas Dieus baisset l’orguel e lo sobrans;

30 e mos orguelhs non es res mas amors,

per que merces mi deu faire socors,

que maint luec son on razos vens merce,

e luec on dregz ni razos no·s ave.

A tot lo mon suy clamans

35 de mi e de trop parlar;

e s’ieu pogues contrafar

fenix, don non es mas us,

que s’art e pueys restortz sus,

ieu m’arsera, quar suy tant malanans,

40 e mos fals digz mensongiers e truans

resorsera en sospirs et en plors

lai on beutatz e iovens e valors

es, que no y falh mas un pauc de merce

que no y sion assemblat tug li be.

45 Ma chansos er drogomans

lai on ieu non aus anar

ni ab dregz huelhs regardar,

tan sui forfagz e aclus;

e ia hom no m’en escus.

50 Mielhs-de-dona, que fugit ai dos ans,

er torn a vos doloiros e plorans;

aissi quo·l sers, que, quant a fag son cors,

torna morir al crit dels cassadors,

aissi torn ieu, domna, en vostra merce;

55 mais vos no·n cal, si d’amor no·us sove.

Tal senhor ai, en cui a tan de be

que·l iorn que·l vei non puosc faillir en re.

Belh Bericle, ioys e pretz vos mante;

tot quan vuelh ai, quan de vos me sove.

Just as the Elephant

Which, when it falls, cannot get up

Until the others, through their trumpeting,

Make it stand up with the sounds they emit,

5 I too want to follow this custom,

Because my wrongdoing is such a heavy burden

That, if the court of Puy, and the pomp

And the rightful merit of the true lovers

Do not get me back up, I will never be up on my feet again;

10 So may they deign to plead for mercy on my behalf

There where begging and arguing do not help me.

And if I, thanks to the refined lovers,

Cannot recover my joyfulness,

I will abandon my singing forever

15 Because there’s nothing left of me;

Instead, I will be living like a recluse,

Alone, without solace, for such is my state of mind;

Because my life bothers and pains me,

And joy feels like sorrow and pleasure like pain,

20 Because I am not at all like the Bear,

Which, when one beats it thoroughly and holds it in contempt, without mercy,

Fattens, improves, and flourishes.

I know full well that love is so magnanimous

That it can easily forgive me,

25 If I failed it by loving excessively

Or if I behaved like Daedalus,

Who said he was Jesus,

And who wanted to fly to the sky in his arrogance

(But God abated his pride and his superiority);

30 And my pride is nothing but love,

Which is why Mercy must come and rescue me,

For there are many instances in which arguing wins against mercy,

And instances in which legitimacy and arguing do not prevail.

I complain to everyone

35 About myself and about my vain discourse;

And if I could imitate

The Phoenix, of which there is but one,

Which lights up in flames and then recovers,

I would light myself up in flames, because I am so unhappy,

40 And my false, mendacious and vile utterance

Will resuscitate as sighing and as weeping,

There where beauty and youthfulness and worth

Are, for it does not take more than just a little of mercy

For there to be everything that is good in one place.

45 My song will be a fixer

There where I do not dare to go

Nor to look with a straight eye,

So much am I guilty and constricted;

And indeed no one seeks to justify me.

50 Best-of-a-Lady, from whom I have fled for two years,

Now I turn to you in pain and crying;

Like the Stag, which, when it has run away,

Returns to die when the hunters shout,

So do I return, Lady, to your mercy;

55 But you do not care, and you are forgetful about love.

I have a lord in whom there is so much goodness

That when I saw him I could not wish for more.

Beautiful Beryl, joyfulness and worth assist you;

I have all that I want when I think about you.