To the tune “Six Beats”—“Green shades of the trees mark the end of spring” | 六麼令 · 綠陰春盡

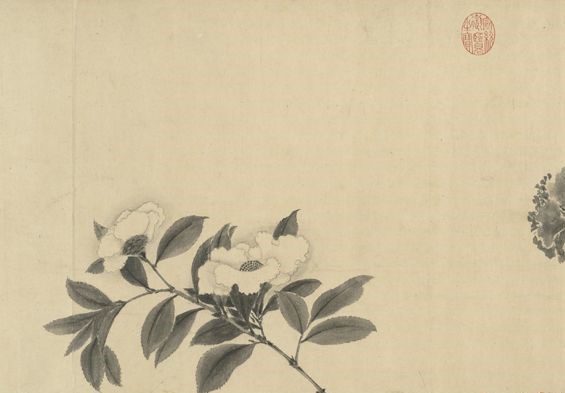

Detail from 宋法常寫生卷 (flower)", 法常, National Palace Museum, Accession Number: K2A000989N000000000PAG [Public Domain]

Read the text (PDF)

Introduction to the Text

In this ci, Yan Jidao adopts the perspective of a young woman longing for her lover. The poet creates an intimate scene through the careful depiction of details―the woman painting her eyebrows, writing songs, and compulsively rereading the letters from her lover while alone in her chamber.

The ci genre of Chinese poetry first emerged in the Sui dynasty (581-619), was further developed in the Tang dynasty (618-907) and matured in the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127). Ci is usually translated into English as “song lyrics”. This is because ci were composed by poets to fit pre-existing tunes. The number of lines, the line lengths, and the tonal and rhythmic patterns of ci vary with the tunes, which number in the hundreds. One common occasion for composing ci would be a banquet: song lyrics would be scribbled down by guests and then sung by musical performers as entertainment. Other occasions for composing and enjoying ci would be more casual: the poet might sing the lyrics to himself at home or while travelling (many ci poets were civil servants of the Imperial Court and often had to travel great distances to carry out their work). Sometimes the lyrics would be sung by ordinary people in the same way as folk songs. This oral and musical quality sets it apart from other genres of poetry in China during the same period, which were largely written texts with more elevated objectives. There are two main types of ci : wǎnyuē (婉 约, “graceful”) and háofàng (豪放, “bold”). The wǎnyuē subgenre primarily focuses on emotion and many of its lyrics are about courtship and love, while the háofàng subgenre often deals with themes that were considered more profound by contemporary audiences, such as ageing and mortality, or the rewards and disappointments of public service.

Yan Jidao 晏幾道 was the son of the eminent ci poet Yan Shu 晏殊. Together, Yan Jidao and Yan Shu are often referred to as “double Yan,” with Yan Jidao being the “Little Yan 小晏 ” and Yan Shu being the “Big Yan 大晏,” reflecting the fact that during their lifetimes they were both the iconic poets of the wǎnyuē (婉 约, “graceful”) subgenre of ci. Unlike his father, who held a prestigious state position alongside a blooming poetry career, Yan Jidao led a far more arduous life. As the seventh son of Yan Shu, he was born into a noble and wealthy family, and had little interest in officialdom at a young age. His lifestyle was extravagant, filled with luxurious banquets, joyous travels with friends, and beautiful courtesans.

After Yan Shu passed away in Yan Jidao’s late teens, the young man realized the imminent financial difficulties which would befall him and abandoned his previously extravagant lifestyle, devoting himself to a political career. However, he struggled to replicate his father’s success and was framed for his involvement in the movement against Wang Anshi’s New Policies (a series of government reforms), which led to him being jailed. Even though he was quickly released, this incident did huge damage to both his political career and his finances. In his later years, he returned to writing ci, and started compiling a collection of his own works, called Little Mountain Ci (小山 词). In the prologue to this collection, he wrote: “I now think of the ones who once drank with me. Some of them have passed away; others fell prey to illness. I read through my collection as if reliving my past sadnesses, joys, separations and gatherings, which now are like fantasies, or a sudden lighting strike, or a faded dream. Thus I could only cover my pages and mourn, for time slips away too fast, and past joys are illusory and unreal.”

As a poet of the wǎnyuē subgenre, Yan Jidao’s lyrics pay great attention to romantic affairs with courtesans. Compared to his contemporaries, Yan Jidao focuses more on the existential and emotional aspect rather than the physical aspect of these affairs, and incorporates more introspection into his poems. Because of the occurrence of specific names and locations in his ci, some of his ci invite a biographical reading. However, as ci are song lyrics intended for multiple performances by different singers on different occasions, there is also a universal character to the sentiments evoked in Yan Jidao’s ci which transcends the poet’s personal experiences.

About this Edition

The original text of this ci is based on the edition by Tang Guizhang 唐圭璋 ( Quan Song Ci 全宋詞, vol 1. Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju, 1965). Punctuation follows the edition. Since ci poetry rarely includes personal pronouns, and gender-differentiated pronouns did not exist in Classical Chinese of this period, the gender of the speaker as well as their perspective (e.g. first-, second- or third-person) must often be deduced by the translator from context.

Further Reading

Chang, Kang-i Sun. The Evolution of Tz’u Poetry: from Late Tang to Northern Sung. Princeton UP, 1980.

- A standard survey of the early history of Chinese song lyrics (romanized as both ci and tz’u).

Egan, Ronald. “The Song Lyric”. The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, vol. 1, edited by Stephen Owen, Cambridge UP, 2010, pp. 434-452.

- An overview of the genre.

Owen, Stephen. Just a Song: Chinese Lyrics from the Eleventh and Early Twelfth Centuries. Asia Center, Harvard UP, 2019.

- A recent new history of the genre.

Tang, Guizhang 唐圭璋, editor. Quan Song Ci 全宋詞. Zhonghua shu ju, 1965. 5 vols.

- A comprehensive edition of ci from the Song dynasty and the source text for the ci in this collection (introductions and annotations are in Chinese).

To the tune “Six Beats”—“Green shades of the trees mark the end of spring” | 六麼令 · 綠陰春盡

六麼令

綠陰春盡,

飛絮繞香閣。

晚來翠眉宮樣,

巧把遠山學。

5 一寸狂心未說,

已向橫波覺。

畫簾遮匝。

新翻曲妙,

暗許閒人帶偷掐。

10 前度書多隱語,

意淺愁難答。

昨夜詩有回紋,

韻險還慵押。

都待笙歌散了,

15 記取留時霎。

不消紅蠟。

閒雲歸後,

月在庭花舊闌角。

To the tune “Six Beats”

Green shades of the trees mark the end of spring;

catkins fly around the fragrant pavilion.

As night falls, I paint my eyebrows in the style that is popular within the palace,

which delicately resembles the curve of the faraway mountains.

5 The wilderness in my heart is not spoken,

but the waves radiating from my eyes tell you the secret.

Painted curtains shield me,

and my newly-written song is marvelous.

I secretly allow the passers-by to overhear it, snatch it away and learn its rhythms.

10 In your last letter you used many cryptic words;

although not hard to decipher, I worry that it’s hard for me to answer.

Yesterday night your poem had palindromes.

The rhymes are precarious and tricky; I’m too lazy to follow.

When the songs fade,

15 please remember the transience of your visit.

No need to waste a red candle,

for as the idle clouds return,

moonlight shall light the old corner of the fences, just by the courtyard flowers.

Critical Notes

Line 2: Here the “fragrant pavilion” (香閣) refers to the residence of the speaker.

Line 6: “Waves radiating from my eyes” (橫波) refers to the emotions of the woman expressed by her eyes.

Line 12: This means that the lyrics she sang would have read the same forwards as backwards.

Line 16: This suggests that there is no need to carry a candle to light the way, because of the moonlight.